A section of Muslim respondents in my study neither attributed economic benefits nor a value rational reason for their support to the BJP and its leader Narendra Modi in 2012 Gujarat elections.

It is possible that the BJP Muslim supporters believed their action to be a step towards amending what they perceived to be their own unworthy behaviour, rather than a compromise of sacred values. In other words, ‘self-blame’.

Salman had witnessed his friend dying in his arms by a police bullet. He also claimed to have secretly viewed a CD containing images of the Naroda Patiya massacre of nearly 100 Muslims in 2002. ‘What a horrible way to kill … wombs being slit open … yes, everyone says Modi had a hand in those killings. So what! Woh apna sab kaam kar sakta hai.’ Salman campaigned for the BJP though claimed to vote for the Congress ‘because my family does’. He vowed to vote for the BJP ‘only after I get to see Modi kaka (term of respect for the elderly in Gujarat)!’ I heard the ‘fascination’ of Salman for Narendra Modi repeated by respondent Noorbanu, ‘He is the future prime minister!’ she said, proudly showing off a laminated photograph of herself with Modi taken during a BJP campaign tour in Delhi in 2010, when we met at her house in Behrampura.

Neither Salman nor Noorbanu said they were direct beneficiaries of rewards, whether monetary or state resources, from the BJP.

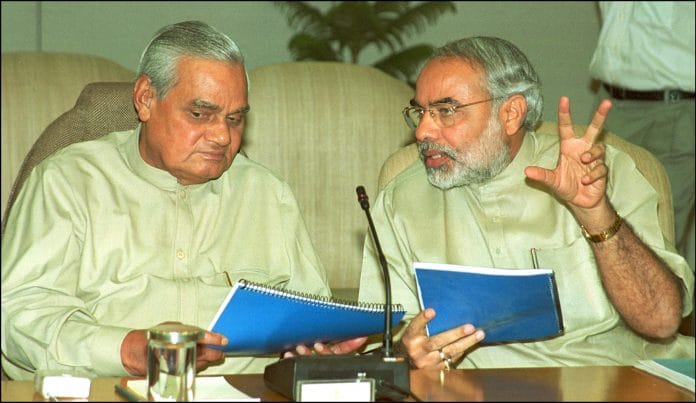

Narendra Modi displayed a charismatic authority that evoked deference. Weber defines charisma as a manifestation of the extraordinary, outside the realm of everyday routine, which rejects external order and breaks traditional and rational norms (Weber, 1978).

Persons perceived to have great power over creation, maintenance, or even destruction of order (including a great capacity for violence) generate awe and deference (Shils, 1965).

Among the top five people who receive the most deference in the United States are state governors, federal legislators, and cabinet members (House, Spangler, and Woycke, 1991), because charisma is directly linked to their power to command over the collective, their decision deeply affecting the order of everyday life.

Salman had not received benefits from the BJP, yet spoke of Modi as a ‘great man’. However, using charisma as an explanatory factor for political support is tautological: we deduce charisma from popular support and then use charisma to explain that support. Further, even if Hindu electors were motivated by charismatic authority, there is no clear explanation for why Muslims would too. Most of all, it is less obvious why pious Muslims would display unexpected flexibility by compromising with sacred values.

In supporting the BJP, they were almost rejecting the party’s anti-Muslim rhetoric and policies and, most importantly, Modi’s refusal to apologize for the violence. Compromising a sacred value in exchange for some material outcome is a taboo trade-off that finds little acceptance (Ginges and Atran, 2009).

Orthodox Sunni Muslims attributed their support to Modi’s skilled governance and the rapid economic progress in Gujarat. As discussed earlier, respondents denied having received any benefits when explicitly questioned. Nonetheless, even if a section of them had been beneficiaries, adding material incentives to compromise over sacred values would increase the saliency of the taboo. It would result in mingling the sacred with the profane and lead to greater opposition to compromise (Ginges and Atran, 2009).

Would this imply the presence of a national identity overlapping a gradually subsiding religious identity among Muslims? Respondents distinguished between the two very clearly. Junaid, a BJP party member in Juhapura, said: ‘Vatan imaan hai, Islam to hai hi. My country is my honour, Islam of course exists indisputably.’ Respondents like Aslam, Mohammed Umar, and Jamal Mohammed had not altered their traditional Islamic attire or subdued their religiosity although they supported the BJP.

One of the characteristics I found common in many testimonies was self-blame. Respondents blamed members of their own religion—and indirectlly, their own selves—for the new-found political ‘compromise’ in favour of the BJP.

Muslim supporter of the BJP, Shaukat, believed that ‘Hindus hate us because we behave uncouthly and are illiterate’; another Muslim BJP supporter, Aijaz, similarly attributed ‘our own illiteracy and jahalat (darkness or ignorance)’ to anti-Muslim sentiment. Janoff-Bulman’s (1979) distinction between behavioural and characterological self-blame is useful in context of past trauma.

Self-blame associated with one’s behaviour—apparent in the testimonies by Muslims—as opposed to one’s character indicates the respondent’s desire to maintain a belief in control and in their ability to avoid a negative outcome in the future.

This is an edited excerpt from Keeping the peace: Spatial differences in Hindu-Muslim violence in Gujarat in 2002 by Raheel Dhattiwala. Republished with permission from Cambridge University Press.

This is an edited excerpt from Keeping the peace: Spatial differences in Hindu-Muslim violence in Gujarat in 2002 by Raheel Dhattiwala. Republished with permission from Cambridge University Press.