Our camp, which had been stationed in Kollar Puliyankulam, was moved to Puthukkudiyiruppu. All the organizations of the Movement took Puthukkudiyiruppu as their nucleus. All the fighters, including leader Prabhakaran, held on to the baseless belief that the Sri Lankan army would never take Puthukkudiyiruppu. Puthukkudiyiruppu was a high-level security enclosure, built with the most extreme security measures.

In 1998, the Leader entrusted the task of releasing the ‘Freedom Birds’ newspaper to me. Though I had had the opportunity to meet with him many times before, it was when we met over my responsibilities for ‘Freedom Birds’ that I had the opportunity to speak to him directly. He expected that I should make many changes in the newspaper. ‘Women’s problems should be brought forward by women. Men can talk about women’s freedom better than women; even I could probably speak about feminism better than you could. But I am not able to fully understand your problems. No man can fully appreciate all the difficulties women undergo. Women must speak and write about women’s issues. It will only be accurate then. It should be mostly women writing in “Freedom Birds”. The female cadres who have some writing skills should be found, and they should be given writing exercises, and have group discussions,’ he noted.

There was a press called Malathi Publications in the care of the Political Wing. It was there that the ‘Liberation Tigers’ newspaper was also printed. When we didn’t have a computer or offset printing resources in Vanni, each letter had to be arranged by hand, each image needed a block, which was an exhausting task in a time of shortages. Because newsprint paper had been banned, we had to get the necessary paper from the Political Wing. I was furiously involved in my administrative work for three of the Women’s Fronts: the education team, ‘Freedom Birds’ and the Political Science division, while also carrying out my propaganda duties in different areas.

Also read: Rajiv Gandhi killer Nalini, who ‘attempted suicide’, is India’s longest-serving woman convict

The eastern province cadres had been through many obstacles, clashed with the army in the dense jungle, walked long distances for many months and were arriving in Vanni to the ‘Jayasikuru’ frontline. At the same time, some troops were heading east from Vanni for some tasks. Under the leadership of the young commander Keeran, some women from the Political Wing, a few medical officers and others formed a unit to head towards Batticaloa.

It was at the end of 1998, or early in 1999. A month after this team had left, some terrible news reached us. In the middle of their journey, many of them had contracted the horrible vomiting disease known as cholera, and as a result many had died. We were informed that as those remaining were in a terrible state, a rescue mission was being undertaken.

A day or two after this news, we were hurriedly called to the shores of Mullaitivu well past midnight one day. When some of the other female cadres and I arrived there, the Sea Tigers handed over the dead and dying who remained from Commander Keeran’s team which had set out for Batticaloa. They were loaded onto waiting vehicles that had already been prepared for them and taken away. I heard that Nirojini, a fighter who was well-known to me, had died of the cholera and been buried in a jungle path. Another fighter, Sutharsini lay there with her eyes closed, looking lifeless like a corpse. The rest were in the same condition. Keeran, who had clung waveringly to his life until then, died the moment they reached the Mullaitivu shore. A separate site had been set up to provide medical care for those most affected. Through intensive care, they were able to recover completely after more than a month. However, it took them several more months to return to good health.

It was only after they recovered that we tried to discover how they had contracted the disease. On their journey they had had a clash with an army troop and were forced to take cover for several days. Their food supplies had run out, and they were forced to eat the dried buffalo meat stores the previous troop had left behind, and drink water from jungle pools; soon after they had been overcome with vomiting and diarrhea. The survivors of that troop told us about their horrifying experiences. As their companions died one by one around them, they were only able to bury a few. They were all wasting away with the disease and had to abandon the bodies of the dead in the forest and escape. All the fighters who heard this story thought it must have been a terrifying experience.

A few months later, the vomiting disease of cholera began to appear among the people of Vanni as well. The medics became alert as soon as they noticed one or two cases showing symptoms of the disease. At a time when they struggled, caught between the hazards of a raging war on the one hand, and poverty and malnutrition on the other, to have a terrifying, infectious, life-threatening disease like cholera spread among them meant unimaginable havoc.

Also read: 28 years after Rajiv Gandhi’s death, a look back at the LTTE-Lanka nexus that killed him

Under the Leader’s instructions, the Political Wing worked frantically side by side with the medics. We took up work raising awareness about the disease and caring for the infected. We split up into several teams and worked around the clock, barely closing our eyes. Facts and warning signs of cholera were explained over loudspeakers, in the Eelanatham newspapers, on the Tigers’ Voice radio and in special flyers to get the information out to the people promptly. The people cooperated fully in our prevention measures. The villagers themselves brought people showing cholera symptoms to the medical facilities prepared for them.

Bouts of malaria kept continuously breaking out among the people at Vanni as well. The people and the fighters were terribly affected by this. Even hearing the names of those medications, ‘Chloroquine, Primaquine, Theraprim’ would make me feel nauseous. The malaria I seemed to catch once every six months caused me a great deal of physical suffering as well. Because the medical division continuously kept using the malaria prevention medication, eventually malaria was eradicated in Vanni.

On 13 August 1998, I went to the Kilinochchi area to meet frontline Commander Theepan to gather some data for a frontline article I was writing for ‘Freedom Birds’. His command centre was set up in the Thiruvaiyaru area near the battlefield. I knew that there had been a clash with the army in the Konavil area on the first night. However, I did not know too many facts about it. A friend of mine who was at the medical centre nearby came running up to me, held on to my hand and said the words that burned into my soul. ‘Thamizhini, our Santhiya was injured in the head at the fighting in Konavil in the Kilinochchi area, and died last night,’ she said. While I had always known that in this terrible unending war, either my sister, or I, or both, might die, the news that my sister, who had followed me into the Movement out of her immeasurable love for me, had lost her life in the field before me, tore at my heart.

She was born on 9 July, my sister Nageswari (Gowri) Subramaniam. She studied at the same school I did. Having joined the Movement in 1992, she received combat training with me in the same camp and was taken into the Leopard Brigade. People who saw her fair-skinned, delicate, beautiful appearance would ask in surprise: ‘Is this really your sister?’ Of the family, she had the most affectionate, mischievous nature, brimming with courage. She would write poetry in her beautiful script and she would draw pictures. At one point in 1997, my sister and I had both got three days leave to go home. The two of us, who had fought often as children fought then as well. Unlike me, spending all my time with my head in a book, she would help my mother with all the housework. She would visit all the relatives. ‘I’ll soon be joining appa. You take good care of amma,’ she kept saying. As usual, I gave her two punches and scolded her, ‘Stop talking nonsense like a lunatic.’

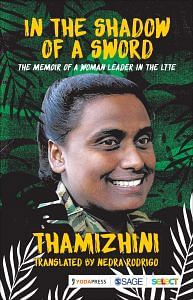

An excerpt from In the Shadow of a Sword: The Memoir of a Woman Leader in the LTTE by Thamizhini, translated by Nedra Rodrigo, jointly published by SAGE Publications and Yoda Press under the Yoda-SAGE Select imprint. 2020, 224 pages, Paperback: Rs. 495 (ISBN: 978-93-5388-683-7).

An excerpt from In the Shadow of a Sword: The Memoir of a Woman Leader in the LTTE by Thamizhini, translated by Nedra Rodrigo, jointly published by SAGE Publications and Yoda Press under the Yoda-SAGE Select imprint. 2020, 224 pages, Paperback: Rs. 495 (ISBN: 978-93-5388-683-7).