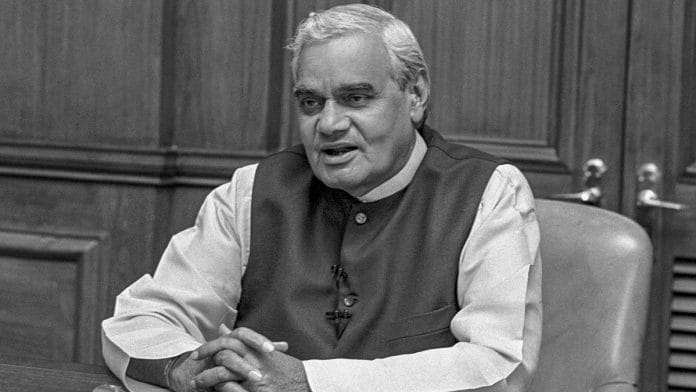

On 24 December 1999, when Prime Minister Vajpayee’s plane returned from a tour within India, I clambered into the car with him for the fifteen minute ride from the Palam Air Force station to his official residence at Race Course Road. Vajpayee was going to turn seventy-five the next day and was his usual reflective self in the car. He did not know then that the last week of the year would bring a major crisis from heights higher than Kargil. I had joined as the prime minister’s private secretary the previous month. On 1 April, I had received the orders out of the blue, when posted as first secretary in the Indian embassy in Berlin.

A telex message that morning said I had been posted as the prime minister’s additional private secretary and should join immediately. I initially thought it was an April Fool prank and then naively wrote to HQ that I needed a few months to finish working on a crucial project of the new Indian embassy in Berlin. Ronen Sen, then my ambassador based in Bonn, gently admonished me to say that one never said no to the PMO. As luck would have it, Vajpayee’s government was defeated by one vote that month and went into caretaker mode, allowing me to leave for Delhi at my own pace. I did join as a deputy secretary in the PMO, just as the Kargil crisis was ending in early July. So, on Christmas Eve 1999, I was about to get my first lesson in crisis management in high places.

I received a message on the Special Protection Group net, from my colleague Anandrajan, the PM’s other private secretary, to call him urgently. As the ‘VIP carcade’ sped towards RCR, I spoke to Anand and then breathlessly told the prime minister that an Indian Airlines flight from Nepal had been hijacked and had landed at Amritsar airport; the crisis management group led by the cabinet secretary was in session and (the principal secretary) Brajesh Mishra was waiting at RCR to brief the prime minister on unfolding events. The PM, seated in the front seat of the white Ambassador, said, ‘Oh’ and asked me if I had anything else. He stared out of the window, deep in thought. We went straight to office, and a few minutes later, a grim Mishra was briefing Vajpayee.

Pakistan’s involvement in this operation became apparent to India’s security experts as the hijack drama unfolded over the next few days, particularly when the hijackers demanded the plane land in Lahore. Plans had been afoot to celebrate Vajpayee’s seventy-fifth birthday on a grand scale, given that he had been sworn in prime minister for the third time. These were instantly abandoned, as the Cabinet Committee on Security met continuously to take stock of the evolving situation. Flight IC-814, scheduled to fly from Kathmandu to Delhi, had finally landed in Taliban-controlled Kandahar, after a tortuous journey that took it to Amritsar, Lahore, and the UAE. A passenger Rupin Katyal, returning from his honeymoon, had been knifed to death. The hijackers brandished the blood-soaked knife before the pilot, Captain Devi Sharan, and assured him that a passenger would be killed every five minutes, unless he did their bidding.

Musharraf’s Pakistan reacted defensively on 26 December with a familiar narrative—suggesting India had launched a false-flag operation. ‘Since October 12 New Delhi has been trying to isolate Pakistan, beginning with its moves to seek suspension of our Commonwealth membership, its unilateral postponement of [the] SAARC summit and now perhaps, India decided to manufacture the hijacking incident,’ Foreign Minister Abdul Sattar told the media. He also dusted off a thirty-year old story—the hijacking incident was ‘not unlike the operation of January 30, 1971 when India planned and foisted a so-called hijacking of an Indian airliner named ‘Ganga’ for manufacturing a pretext to deny Pakistan’s rights and block overnight flights by PIA between East and West Pakistan.’ He denied Indian assertions that the hijackers boarded the Indian aircraft at Kathmandu airport after disembarking from a PIA flight.

Also read: IC 814 hijack was a victory for Masood Azhar—and the moment of his strategic downfall

For India, the hijacking was real enough. Pakistan’s role was clear and exasperating. Relatives of passengers were marching in protest, a pressure group the government needed to mollify, their anxiety amplified and exaggerated by over the top electronic media reportage. Worse, despite the multiple hijacks of a decade ago, no protocols or reflexive anti-hijack measures seemed to have come into play. India’s crisis managers were floundering for a coherent response.

High Commissioner Parthasarathy watched the drama from Islamabad with a sense of déjà vu. He had handled two hijackings when posted in Karachi in 1984; during one of these which terminated in Dubai, the ISI had actually provided a pistol to the hijackers at Lahore airport. Familiar with the modus operandi of the hijackers, the high commissioner predicted to Delhi that the flight would land in Lahore after Amritsar. He suspected that the Pakistanis would not be keen to let the flight stay in Lahore and it might end up in Dubai like the last time. Hoping to negotiate in Lahore, he asked the Pakistan foreign office to facilitate his trip to the city. The foreign office went through the motions of trying to transport Partha from Rawalpindi to Lahore, but told him at the airport that the hijacked flight had taken off from Lahore.

The high commission team was then contacted by Taliban representatives in Pakistan, who told them that the final destination of the aircraft would be Kandahar in Afghanistan. In his negotiations with the Taliban representatives, the high commissioner insisted that no terrorist would be released. On 28 December, he was told to step down from his role in negotiation since this was now being handled by a team from Delhi. The ISI’s links with the Taliban were well-established and their connection with the hijackers was now clear to the high commission, as well as the Indian negotiating team that reached the tarmac in Kandahar. Counsellor A. R. Ghanshyam from Islamabad joined the Kandahar team and saw Urduspeaking, apparently Pakistani, handlers guiding the Taliban. Partha soon learnt that after intense negotiations, India had agreed to release three jailed terrorists to secure the hijacked passengers and plane.

Under pressure to resolve the issue before the new millennium began, Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh informed the Cabinet Committee on Security that he would personally go to Kandahar. His act came in for criticism since the three terrorists exchanged for the passengers were on the same flight as the foreign minister. But Singh defended himself later to point out that only one aircraft could land at the airport and bring the passengers back. The final act of the drama was enacted on the last day of the millennium, 31 December 1999, when three terrorists were delivered in Kandahar in exchange for the passengers who returned safely.

To Parthasarathy, the decision to exchange terrorists for passengers, was reminiscent of the one in 1990 in the case of the kidnapping of Rubaiya Sayeed. He rued that this capitulation would tell the Pakistani establishment that India was a soft and vulnerable state. As it turned out, each of the terrorists would be responsible for multiple murders in their respective Kashmir-focused terrorism careers launched with ISI support. Maulana Masood Azhar would go on to found the Jaish-e-Mohammed in 2000, responsible for spectacular acts of terror, including on India’s parliament in 2001 and in Pulwama, Kashmir, in 2019; Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar was assigned to training Kashmiri terrorists in POK; Omar Sheikh was involved in plotting 9/11 in 2001 and then ‘arrested’ for the murder of the US reporter Daniel Pearl in 2002, only to have his death sentence reversed in seven years.

The NDA government, in its new term, had faced its first major crisis with the eighth Pakistan-related hijacking, evoking unhappy memories of the series of hijackings of the 1970s and 1980s. This was yet another manifestation of terror, with a global dimension, a humanitarian situation and a media spectacle that reduced policy options. Vajpayee had mixed feelings about how the crisis had ended. When I informed him of a felicitation function to celebrate the success of the operation, led by the family of Captain Sharan, the prime minister asked me, ‘But why did he not ground the plane in Amritsar?’

Vajpayee’s abbreviated term of thirteen months, followed by the caretaker phase of six months had seen the Pokhran explosions, the Lahore visit, and Kargil, all connected deeply to one another. But the decision to go nuclear had redefined diplomacy between the estranged neighbours. Hopes that were revived of the nuclear-armed rivals forging a new détente with Vajpayee’s bus diplomacy to Lahore had been dashed with Pakistan’s aggression in Kargil; this hope plummeted further for India as the millennium ended with the traumatic hijack.

This excerpt from Ajay Basaria’s book ‘Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan’ has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from Ajay Basaria’s book ‘Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan’ has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

Continue to provide us with more of such contents.