Allied POWs took precautions, with those in Lamsdorf being ‘secretly organised into fighting units’ in case the German guards turned on them at the end. Meanwhile Captain Anis had been moved around from camp to camp, ending up at Oflag 79 at Braunschweig. In March 1943 he had written to his cousin Shahid Hamid from Annaburg to say, ‘I am quite well by the Grace of God’. Clearly the tough conditions had not yet started to bite. A year later, things had changed considerably, as the RAF and the USAAF were now carrying out regular bombing raids in Germany – the Americans by day and the British by night.

For a white British officer like Major Hitchcock, surrounded by hundreds of men like him, such privations would have been easier to bear. Anis was different: he was a fish out of water, and an odd fish at that. He was one of very few Indians and fewer Muslims, with a sneaking feeling that he was only still in the camp because he had not given that one word ‘yes’ to Bose, a word that he could so easily have given but for his sense of izzat or honour. His life must have been lonely: one can feel his need for company in his cards to his cousin Shahid. Even his batman, Driver Dost Mohamed, had been taken from him, having died in the camp at Berlin in November 1941; his name is inscribed on the Dunkirk memorial as one of the Indian soldiers whose grave is unknown.Soon before the liberation of Oflag 79 Anis was moved around with other prisoners by train. The camp was liberated by the US Army on 12 April 1945, and Anis was horrified when he saw the newly freed prisoners looting cameras, binoculars and radios: ‘like children let loose … breaking into homes and shops and carting away lots of stuff ’.

In 1945, the men of 22nd Company were reunited in East Anglia, those who had joined the Germans and those who had chosen to sit it out. The India Office and British military intelligence had known of the existence of the Indian Legion for some time, and their plans were ready. A new intelligence unit had been set up: the Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre (CSDIC). From July 1943 they were talking about the men as ‘Hitler Inspired Fifth Column (HIFs)’ and had devised a colour code for grading POWs and legionaries according to their loyalty – black, white and grey: the darker the colour, the deeper the treachery. In January 1944, Molesworth of the India Office saw a report in the London Evening Standard with a photo of a Sikh in German uniform. Molesworth’s response was to have lunch with the editors of nine prominent British newspapers and ask them not to publish anything on HIFs. They concurred. When the Allies invaded Europe in June, a Major de Gale from MI5 accompanied them with the specific purpose of ‘security screening of Indians’. The British were taking no chances: all POWs would be questioned and sorted before being allowed back to India.

Also read: The glorious battle Indian soldiers fought in Italy, on a terrain as tough as the Himalayas

Several camps were established in East Anglia in the summer of 1944, with their HQ at Thetford.

A separate hospital with 600 beds was made available, and all POWs were treated well, with special provisions for their welfare. As they were liberated, they each received a Red Cross gift bag from the ICF, with more waiting for them in the camps. They were given money to send home and spend at the Navy Army and Air Force Institute (NAAFI) shop, and could earn more by volunteering to help with the potato and beet harvest. There were trips to London and to Woking Mosque and a Sikh gurdwara (temple), and as it was a cold winter, there were snowball fights and a snowman competition. The King visited in June 1945 and inspected 4,000 released POWs – the India Office was being very careful not to impugn the reputation of those who had remained loyal to the Crown. The old K6 newsletter Wilayati Akhbar Haftawar was restarted in November 1944 with the usual mixture of news from India, war news and photos of the men themselves. In keeping with the new end-of-war mood, there was also a spread of photos of the newly liberated Belsen concentration camp. The very last photo was a symbol of post-war British hope: St Paul’s Cathedral lit up for the first time since 1939. The sepoys, itching to get back home to India, probably did not share this sense of national optimism.

One of the camps – at Cranwich, north of Thetford – was designated as a ‘black camp’ and housed the CSDIC men. The team of Indian and British interrogators worked their way steadily through the captured legionaries and civilians. ‘Grey’ was split into dark and light shades, and the precise definition of black and grey evolved. By August 1945, grey could include those who had served in 950 Regiment, provided they had been ‘misled by their leaders or persuaded to join the enemy by torture or the hope of better conditions’. CSDIC even requested that Anis be sent for questioning, but that he should not be sent under escort. They wanted to talk to him, to hear his story, but they did not wish it to appear that he was under suspicion. In fact, he was back in the army in a few short months; clearly he was not deemed to have crossed the line to black ‘traitor’ status. Abuzar was a different matter. His interrogation report is one of the most detailed, and its conclusion is unequivocal and damning. Abuzar was branded a ‘traitor who, on his own showing, has been one of the leading recruiters and a prominent member of 950 Regiment ever since June 42’. It added that there was little doubt he had used violence in recruiting men to the legion, and that the Germans considered him ‘thoroughly reliable’. Although he had later acted in support of the Allies again, through his work with Max Joiris, the author of the report considered this was due ‘not to a change of heart, but to a desire to feather his nest’. Finally, it concluded, ‘It is considered that he constitutes a permanent danger to security and it is recommended that he be categorised Black.’

Also read: Moving towards darkest hour of coronavirus, India can take strength from WW2’s Dunkirk moment

By October 1945 the camps had done their work and were shut, with a grand total of 9,711 recovered prisoners (black, grey and white) having been processed and returned to India. In some cases the black and the white were sent home together on the same ship, like the SS Aronda in July 1945. Either CSDIC were unconcerned about the troops’ loyalty now the war in Europe was over, or they did not have enough shipping to worry the point. A report by the adjutant-general in India clarifies that all returning POWs would get an advance of seventy rupees and that they were ‘likely to be in a rather pleased and excited frame of mind’.

The status of the ‘loyalists’ and the ‘revolutionaries’ of the Indian Legion was changing, and would shift further in tune with India’s wider movements.

The ‘blacks’ of 950 Regiment, with twenty or so from 22nd Company among them, returned to India in the summer of 1945. They found that public opinion was in a state of flux. The men from Europe, Abuzar among them, were imprisoned at Bahadurgarh, just outside Delhi.From there they witnessed the extraordinary procedures of the Red Fort trials. In November three of the INA’s senior officers were put on trial for treason – one Hindu, one Muslim and one Sikh: Prem Sahgal, Shah Nawaz Khan and Gurubaksh Singh Dhillon. Public opinion swiftly moved against the British, with Nehru part of the defence team, and Gandhi expressing his support for the men in jail. The men were found guilty and sentenced to death, but the public furore was considerable, with the INA men ‘widely admired’, and Auchinleck ordered the sentences be commuted. This was a decisive victory for the nationalists, and the chant in the streets was:

Lal Qila se aayi awaaz

Dhillon, Sahgal, Shahnawaz (From the Red Fort comes the cry Dhillon, Sahgal, Shah Nawaz)

Soon after that, all the remaining men of 950 Regiment (and the INA) were discharged. By May 1946 half of the RIASC ‘greys’ had been reclassified ‘white’ and sent on leave. The ‘traitors’ were in the process of being recast as ‘heroes’. British rule in India had passed the point of no return.

Also read: ‘Dunkirk’ has a message for Indian war-mongers

By the end of 1945, all the men of the Indian Contingent were back home, except those left behind in graves in Europe. Between them they had seen the highways and byways of Wales, England and Scotland, camps in France, Germany, Spain and Poland, army bases in Belgium and the Netherlands, and safe havens in Switzerland and Gibraltar.

After the Red Fort trials there was some concern that ex- members of the INA (including the legion) were being employed in government jobs, thus taking jobs from soldiers who had stayed loyal to the British. But the attitude towards the INA was a nuanced one, according to a report from 32nd Company at the end of 1945:

INA Trials are arousing a great deal of interest. The general feeling is that under duress of hunger and mal-treatment the action of the majority in joining the INA is understandable. The recent Govt announcement that clemency will be shown to these people was greeted with enthusiasm. Whilst all agree that leaders who mal-treated their own countrymen should be punished, there have been no sign of real hate against these people.

The reconciliation with the INA and its legacy was an indication of the increasingly questionable status of the army in post-war India. The men were back at home, amid a world at turmoil. Their unique experience in having travelled 7,000 miles to help was overlooked by their neighbours and would soon be overtaken by the rush of events. Only the men themselves carried the memory in their hearts. In far-off Britain, scores of people who knew them did the same, nurturing a small cache of stories of these smiling turbaned strangers who had come into their lives, changed them forever, and then disappeared.

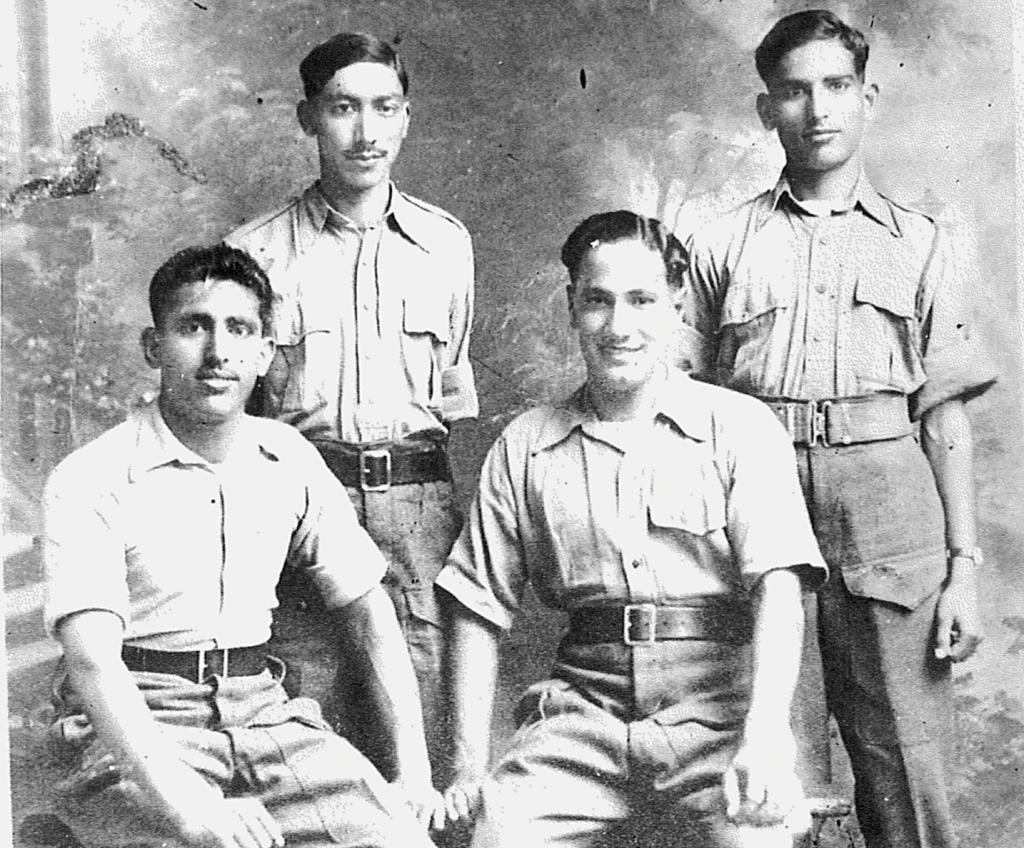

This excerpt from ‘The Indian Contingent: The Forgotten Muslim Soldiers of the Battle of Dunkirk’ by Ghee Bowman has been published with permission from PanMacmillan India.

This excerpt from ‘The Indian Contingent: The Forgotten Muslim Soldiers of the Battle of Dunkirk’ by Ghee Bowman has been published with permission from PanMacmillan India.