India Today, the national news magazine, did a cover story in August 1996 on the prime minister’s office (PMO) that was just about settling down. Deve Gowda was barely one-and-a-half-month old in the chair when the story appeared, but there was already an element of surprise, as well as awe, in bureaucratic circles about the manner in which he had put his office together and the talent he had infused. He had brought in officers known for their integrity, efficiency, and decades of administrative experience to assist him. It indirectly spoke about Gowda’s intent to govern well and leave behind a good name.

Gowda as a chief minister and a minister in Karnataka had always preferred credible and competent officers with diverse caste, religious and linguistic backgrounds. Almost as a rule, he never packed his office with people from his own caste. He had always placed enormous trust in his officers, fought for them and never humiliated them. He never demanded their loyalty but expected only professionalism and dedication. But since such expectations were so rare in any political milieu, he commanded loyalty of the best too. However, he never verbalized his work ethic or flaunted them as precious beads in his value necklace. When asked why he had never spoken of these things, Gowda sarcastically said: ‘I left all such things to my friend Ramakrishna Hegde. It was he who always claimed a patent to “value-based politics”. It suited his image.’ All this was familiar in Karnataka, but in Delhi, where he was seen as a ‘dark horse’, they were blind to his governance record. They projected him as someone picked up by the wayside and made prime minister, as someone who could neither trot nor gallop.

In this backdrop, the India Today cover story was a fair piece of reporting. The copy said: ‘Helping him (Gowda) are a team of handpicked bureaucrats who he has worked with in Karnataka . . . with whom he has a steady rapport. Heading the trio that has moved from Bangalore to New Delhi is Satish Chandran, the former chief secretary, Karnataka . . . Respected for his integrity and honesty . . . Chandran is now Deve Gowda’s key official, vetting all the files before they reach him. And, as a political aide of Deve Gowda says, “He occupies the seat mainly because he will not become a power broker.” A problem that (P.V. Narasimha) Rao’s senior cabinet ministers faced with (A.N.) Verma (Rao’s principal secretary), considered the most powerful man after the prime minister, was clearing of Rao’s political appointments; keeping even Governors waiting for three days and returning without meeting Rao. Deve Gowda too has built up a parallel team, but unlike his predecessor, there was a strong separation between the bureaucratic and the political turfs.’

Also read: Before Deve Gowda, VP Singh was asked to be PM of United Front. He hid in his flat, car

Getting Started

The question as to who will run the PM’s office came up as soon as Gowda reached Bangalore as a designate to the chair. He called Meenakshisundaram, his principal secretary as chief minister, and asked him to make a shortlist. Someone from the Karnataka cadre would make it easy for him to relate. Meenakshisundaram knew that it was a tradition to pick a retired officer to head the PMO. Within a couple of hours, he went back with two names he knew Gowda respected: T.R. Satish Chandran and J.C. Lynn. Both had experience in Delhi, and both were former chief secretaries of Karnataka. Chandran was older to Lynn. Gowda was delighted. Either choice would not have made a difference to him. He wanted Satish Chandran to be sounded first: ‘If Satish Chandran sahebru agrees, I will be happy. He was our chief secretary. We should not now call him secretary, it is too small for his stature. We should give him a higher designation. Perhaps we should call him senior adviser,’ Sundaram recalled Gowda telling him.

Chandran those days was with M.Y. Ghorpade, a former finance minister of Karnataka and the erstwhile maharaja of Sandur. He had been inducted to the board of the Sandur Manganese Company. Meenakshisundaram went and spoke to Chandran. His first reaction was that he should consult Ghorpade and it would not be fair to take a decision without consulting him. ‘I don’t want to do anything behind his back. I am sure Mr Ghorpade will agree because it is a great honour that a Kannadiga is going to be the prime minister of this country, and we should all stand by him.’ Chandran also added: ‘I am willing to come and work. But please tell the PM-designate that in the government of India nobody will bother about an adviser. I would prefer to be called principal secretary to the prime minister.’

By then, officers had started lobbying. Some approached Thippeswamy to express their interest because they knew he had access to the big man. There was one particular additional chief secretary-rank officer from Karnataka who even prepared a full list, totally unsolicited, of officers who Gowda should pick from the IAS pool across the country. He had specifically spoken against Chandran and Lynn. Thippeswamy was himself reluctant to go to Delhi because he thought as a non-IAS officer, he may not exactly fit into the PMO structure, plus his family was against his relocation. But he had already become indispensable. He had started handling the temporary hotlines that the SPG had set up in Anugraha, Gowda’s chief ministerial residence in Bangalore. There was a call nearly every minute from Delhi and he had temporarily been designated as the liaison officer. He was being continuously briefed on what was being planned and how things would be taken forward. His job was to convey the information to Gowda and take his consent. Thippeswamy was practically given no choice. He had to relocate. Satish Chandran took charge on 11 June, the day Gowda sought the vote of confidence in the Parliament. For eleven days, from the day he was sworn in as PM till the day he was confirmed, many senior officers met Gowda and lobbied for PMO jobs, including the top job of principal secretary. Gowda had listened to all of them, was unfailingly courteous, but had not committed anything.

Also read: Indian scientists planned nuclear test in 1997. But PM Deve Gowda gave 3 reasons to say no

The first big task for the PMO, before Chandran arrived in Delhi, was the ministry formation. The PM was very particular that the entire cabinet should take charge in one go. He thought it would avoid unnecessary confusion and competition for portfolios. The senior cabinet ministers would anyway be picked in consultation with party bosses, and in some cases, the party bosses themselves would be joining the cabinet. That was being personally dealt with by the PM, but when it came to ministers of state, Gowda told Meenakshisundaram that his coalition colleagues would submit names, and he should sit with Yugandhar and fit them into different ministries given their backgrounds and suitability. Once the list was complete, he would scrutinize and clear the names. The only guideline that Gowda gave was that he wanted a Muslim as a junior minister in the home ministry. Since Yugandhar had been in the PMO, he sifted and matched names and ministries, and the list got ready before the deadline. They had proposed a Muslim name from Bihar as junior home minister but soon realized that it was an error because he had criminal cases pending against him. His name was replaced later with that of Maqbool Dar, the MP from Kashmir.

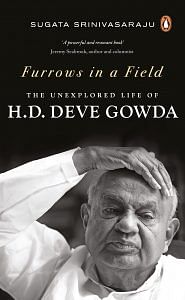

This excerpt from ‘Furrows In A Field: The Unexplored Life of H.D. Deve Gowda’ by Sugata Srinivasaraju has been published with permission with Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘Furrows In A Field: The Unexplored Life of H.D. Deve Gowda’ by Sugata Srinivasaraju has been published with permission with Penguin Random House India.