At the end of the press release, they listed key IFD organizers and gave Jitendra Kumar’s phone number (301-365-1562) for any further queries there may be. Special attention was also drawn to a news conference at 2 p.m., after the demonstration, at the East Lounge of the National Press Club. ‘How to mobilize people for the protest beyond tapping our own known networks? That was a big concern with us. But someone came up with a bright idea. They picked up the telephone directory of the Washington D.C. area and started calling people with Indian surnames. It had a limited success,’ SR recalled.

The next day, around seventy-five to eighty demonstrators assembled at Dupont Circle and moved towards the embassy. SR remembers that one Eric Gonsalves, who was officiating in the absence of the ambassador, came out to meet the protestors. When they tried to hand over the petition to him, he refused to accept it by saying that he did not have orders to accept it. That is when they symbolically left the petition on the steps of the embassy. The picture that D.C. Agrawal captured on that day was in no way amateurish. It had the powerful resonance of a professional news frame. As copies of the petition lay on the steps, the picture was so framed that there were no faces in it but was filled up with only dark pants and shining dark boots. The security personnel were caught suppressing their own dwarfed noon light shadows. If placing the petition on the steps in gentle protest had its own symbolism, D.C. Agrawal’s photograph created a deeper poetry of protest. The petition that they left on the steps that day also had 500 signatures of Indian Americans with the name of the American city and state they belonged. The one additional point in the petition, besides those reflected in the press release mentioned above, was the demand to release JP and all other political prisoners.

The placards they held had the following rather predictable slogans. Sample some: ‘IS THIS THE INDEPENDENCE WE FOUGHT FOR?’; ‘DEMOCRACY YES, DICTATORSHIP NO’; ‘ONE GANDHI LED THE FREEDOM MOVEMENT THE NEXT GANDHI ENDED IT!’; ‘PREVENT MURDER OF DEMOCRACY’; ‘SAVE DEMOCRACY’; ‘NO DETENTION WITHOUT TRIAL’; ‘LIFT PRESS CENSORSHIP’ etc. Interestingly, in one of the photographs that D.C. Agrawal captured, there was a placard that read ‘SAVE THE REPUBLIC’ in five Indian languages: Kannada, Tamil, Odia, Hindi, Bengali and Gujarati. There were also independent Hindi placards. This was indicative of the diversity of the demonstrators and the larger IFD group that had been formed.

In the leaflet that they distributed at the protest venue that day, IFD members tried to describe themselves for the first time. The frame they created was unique. They linked their ideas of development and democracy to be interconnected and interdependent. Under the subhead ‘WHO WE ARE’, they said they were a ‘recently organized group of Indians and friends of India in the United States who have come together to help protect the Indian democratic system and help it survive the current crises.’ They added, ‘Some of us were previously involved with developmental activities and programs and are now in these activities because of the current events in India, particularly the declaration of the national emergency, the censorship of news and mass arrests, the future impact of which is foreboding.’ Next, they answered, ‘WHAT WE DO: In order to help the Indian democratic system survive and flourish, we raise our own voices and organize the voices of other Indians and friends of India around the world against the current actions taken towards the suppression of the fundamental rights of the Indian citizens and the throttling of the Indian democracy.’

However, the more interesting explanation they offered about themselves could be seen under the ‘WHAT WE BELIEVE’ section. It read like a quasi-philosophical treatise in quasi-academic language that went beyond the distractions and anxieties of everyday developments and real politics. Their emphasis was on the individual and the citizen, not on groups or castes or communities or communes. It had an imprint of America and not exactly the socialism that was being spoken about in India either by Indira Gandhi or stalwart socialist leaders in the Opposition. The repetitive use of the phrase ‘development of a nation’ read like a poor imitation of King’s alliterations in his iconic speeches:

We believe that a democratic social, economic, political and educational system, a system which is democratic not only in its ideas but also in its practices is suited for India’s development because: a. Development of a nation is only through the development of all its individual citizens and that can be done only in a system which believes in the individual man, not as a means but as an end, believes in his worth and dignity, and in his rights and responsibilities. b. Development of a nation requires that there be an atmosphere, not of fear and coercion but of self-development and hope which nurtures the growth of all its citizens. C. Development of a nation requires the guarantee of fundamental rights for all its citizens. Freedom of thought is not just an intellectual luxury but a necessary catalyst to which society owes its progress, its scientific and technological as well as its humanistic advances. d. Development of a nation, to the point where violence and conflict are reduced, if not eliminated, requires raising the consciousness level of all its individual citizens not just that of the people in power.

In the rest of the leaflet, they reproduced the demands they had made in the petition, besides adding that the 1971 Emergency should also be withdrawn as well as MISA, DIR and other laws that ‘militate against civil liberties’. Other than the names that we have already become familiar with the IFD, there were some new names at the end of the leaflet with their phone numbers, including R. Bhutada of Houston, Texas, N. Sharma of Denver, Colorado, M. Bhujwala of Los Angeles, California, Harsh Kachhi of San Diego, California and Krishan Jindal of San Francisco, California.

Headlines and the Elderly Ascetic

As mentioned earlier, IFD held a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington D.C. The East Lounge was packed with journalists from both the print and television media. The IFD members explained who they were, what their demands were and what they expected from the international press. They were, in turn, asked about JP’s arrest, Morarji Desai’s arrest, what was really happening in India and how it would all turn out eventually. There was also a keenness to understand the character of the JP movement. They wanted to understand emergency laws. Questions on socio-economic conditions in India also came up. It was an unusually long press meet. D.C. Agrawal remembers that it went on for close to a couple of hours. When they thought everything had gone on fine and they had stuck to their notes, Jitendra Kumar made an off-the cuff remark, which D.C. Agrawal thought disturbed the measured approach that noon. It was also something they had not been discussed in the IFD core committee meeting.

Our buddy, Jitendra Kumar, one of the four on the podium including myself, suddenly ventured into a conspiratorial zone. He said that he had got news that the USSR was supporting Mrs Indira Gandhi with her emergency by sending troops via Afghanistan and Pakistan. It was an absurd claim. It was a room filled with serious journalists from credible news organisations, they immediately balked at this unverified remark. After that one could see the attention of the room drifting away. I was all of 27 years at the time, and in my innocence and inexperience, had not realised that [the] people who had gathered at the demonstration earlier in the day came from different backgrounds and had different agendas.

D.C. Agrawal still preserves in his files the notes he had made for his maiden press conference on a crumpled sheet of paper. It was a kind of memorabilia that stayed with him for decades, along with other papers. He knew it had no larger meaning outside of himself, yet he had never discarded it. Perhaps he thought that the sheet of paper bore witness to his life’s unusual alignment with a larger historical happening. It was testimony to a larger purpose he had given himself in his younger days, outside the boredom of everyday living and his professional exigencies. One wonders if people preserve their old notes, cards and letters, in the forgotten corners of their desks, cupboards, basements, lofts and garages because they want them, from time to time, to authenticate their own lives for an autobiography they are constantly revising in the attics of their mind. An autobiography that they construct for an audience of one—themselves. An enterprise that quietly validates the significance of their life and living. Something that echoes in soulful chambers within, that their journey was, after all, not frittered away. Notes to oneself and other such material, perhaps, are private archives for amorphous chapters of such a deep human need.

D.C. Agrawal’s press conference notes are on a single sheet written in blue ink. The handwriting is hurried but legible. It is divided diligently into three parts. The first part says, ‘WE ARE GOING TO DO’ and then the details in five points:

1) We are going to organize regional centre major vs Indian centres (not clear what this means).

2) Boycott official function of Independence Day Aug 15. Parallel protest on August 15.

3) More organized and in larger numbers on Aug 15.

4) Plans after Aug 15 are currently being discussed and shall be released based on events. It has been only 4 days since this [sic] things started.

5) If political opponents under detention are not allowed right to appear, we shall be taking their case to international forums.

The second part of the note, ‘WHAT HAPPENED TODAY’ had brief points on what had happened in the earlier part of the day before the Indian embassy. In the third part, ‘OUR DEMANDS,’ he had a line to remind himself to reiterate their ‘four very basic demands’ discussed above. Across the right margin of the note, running bottom to top, a line says, ‘He is really too good!’ One is not sure whom Agrawal was appreciating; it was certainly not Jitendra Kumar!

SR clearly recalled that, initially, he was not in support of holding a press conference after the protest before the embassy on 30 June. He was apprehensive for a variety of reasons. He was of the view that IFD had just been started and they had to build the organization before speaking to the media. In another corner of his mind, he thought Shrikumar, who was pushing for the press meet, was being rather ‘ad hoc’, that he had not done sufficient planning for such an exposure. Shrikumar, however, was shrewd in his assessment:

SR said:

He argued that the media was watching at the events unfolding in India and were keen to get a perspective from Indians in the United States. We should cater to their legitimate need and establish the IFD name. I was convinced by what Shrikumar said. However, since I did not have the experience of addressing press meets, I said I will not go on the podium. Shrikumar, D.C. Agrawal, Jitendra and one other IFD colleague were on the stage. I was in the hall when the press meet went on. All was well until Jitendra made an absurd and irrelevant comment. I grew a little tense.

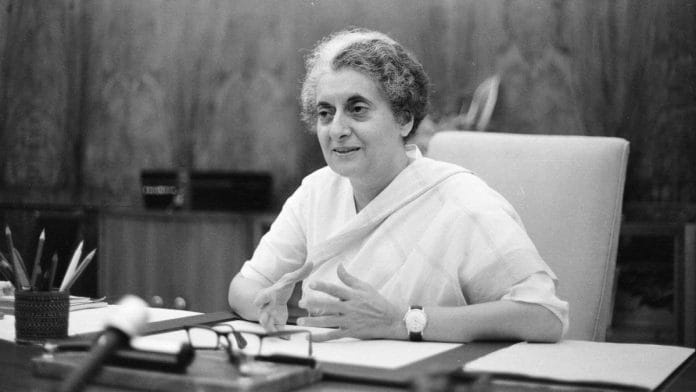

Press coverage, the next day, was more than encouraging. The Washington Post not only published a report but also a three-column picture of IFD protestors placing copies of the petition on the steps of the embassy on its front page. Larry Morris’s picture made it look like the protestors were bending in a gentle Gandhian way to place the petitions at the feet of the security personnel. The security personnel’s sternness of posture subsumed pistols and batons hanging from their hips. They had formed a wall blocking the door of the embassy. The report established that there were about seventy-five people protesting the ‘recent steps of Indira Gandhi to jail hundreds of political dissenters, restrict the rights of Indian citizens and censure the Indian press’. It also said that the protestors brought with them ‘several pages of a petition bearing what they said were 500 signatures of Indian citizens who deplore Mrs Gandhi’s dictatorial policy’. On charge d’affaires Eric Gonsalves refusing to accept the IFD petition, the Post quoted a protestor: ‘Just seven days ago, the people of India could meet with their president. Now this group (the protestors), the so-called elite of India, cannot even see an official so puny as the charge d’affaires of this embassy.’

On 1 July, the Washington Post had a reflective editorial on India and democracy as well. It started out by saying, ‘Mrs Gandhi has gone too far—much too far.’ It then said, ‘If last week the instant question was whether Mrs Gandhi would survive, this week it is whether Indian democracy will survive.’ It said that Indira Gandhi was acting like a ‘British regimental commander imposing order in a restive colonial province’ by locking up political rivals by the thousand and choking off the local and foreign press. Going beyond the immediate, the editorial turned to the larger idea of democracy in a poor country like India:

To many, Indian democracy has been at once blessing and burden: a system glorious in its political values and promise but one of uncertain political advantage to a large poor nation trying to modernize against breathtaking odds; the pride of the educated classes but something of little direct meaning to the country’s illiterate and miserable majority; a cultural lifeline to India’s former masters and its friends in the West but a barrier between it and the Soviet Union, its chief foreign patron in recent years.

The editorial then asked if it mattered to Americans how democracy fares in India.

Americans in their chastened post-Vietnam mood are uncertain whether it is appropriate or right at all to want to see our system of democracy and free enterprise take root in foreign soil: It sounds imperialistic, risky . . . Precious as are American values at home, Americans can hardly place a higher premium on the fortune of those values in a foreign land than do the people of that country themselves.

On 30 June, the morning of the IFD protest, Robert Keatley, wrote a lengthy piece on the ‘fading of freedom’ in India in the Wall Street Journal. SR and his other IFD friends were not aware of it. SR learnt about it in an office meeting when the president of Quasar Electronics, where he was a senior manager at the time, brought it to his attention. The Wall Street Journal’s assessment was not very different from that of the Post, but it brought far greater attention to the economic crisis in India. The piece began by saying, ‘For all its many virtues, Indian democracy has also been part failure and part fraud.’ It said Indira Gandhi, by imposing the Emergency, had behaved not like her left-wing friends, but like the world’s ‘right wing dictatorships’.

This excerpt from The Conscience Network by Sugata Srinivasaraju has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from The Conscience Network by Sugata Srinivasaraju has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.