By using an indirectly elected provisional parliament to amend the ‘heart and soul’ of the Constitution even before the inaugural general election, disregarding widespread protestations – from the president, the speaker, the leader of opposition down to civil society organizations – Nehru failed to account for the need to maintain constitutional rectitude and form positive conventions for the future; even if he believed this was a fair trade-off for the sake of progress or demanded by the gravity of the issues at hand. Transplanting Westminster-style democracy to India, noted the constitutional historian Harshan Kumarasingham, ‘demanded instant conventions as the polity had not had the benefit of centuries of evolution. Therein lay the problem and the opportunity for the local executive.’

With the First Amendment, India’s constitutional journey began with an unhealthy emphasis on executive supremacy, deprivileging individual rights and treating Fundamental Rights as secondary to more important electoral and ideological considerations. Such open disregard for democratic propriety on the part of independent India’s first government even if not extra-constitutional in itself, helped foster a spirit of authoritarianism and constitutional subversion, as Mookerjee had predicted. Originally conceived as permanent guarantees, Fundamental Rights became – to quote Chief Justice Hidyatullah – ‘the plaything of special majorities.’

Much of this was exacerbated by the reasoning Nehru presented in Parliament as justification for the amendment: judicial striking down of legislation as a denial of democracy, Fundamental Rights as obsolete remnants of the French Revolution, the primacy of the government’s promises over the Constitution, the Constitution as an impediment to the will of the people, recurring references to unseen dangers that threatened the survival of the country, the need to curb ‘unbridled criticism’, the duty of the state to champion socio-economic transformation over the protection of individual freedom and finally, the desire to fulfil the promises he had made to the electorate. ‘It is not good for us to say,’ he argued, ‘[that] we are helpless before fate and the situation we have to face at present.’ In sum, Nehru’s reasoning represented almost an inversion of the constitutional order, in the express pursuit of a political agenda.

Also Read: India’s Constitution makers Nehru, Patel & Ambedkar were divided on parliamentary system

There were many reasons that Nehru’s views (and the amendment itself) were considered problematic – his timing before the inaugural general election, the use of an indirectly elected, unicameral and provisional parliament to amend a constitution barely fifteen months after its creation, the amendment’s consequences for civil liberties, the disregard for democratic propriety and the need to set good precedents. An alternative cause for discontent was also the widespread belief outside the government that there was no clear and pressing reason for the amendment in the first place. Mookerjee was the sharpest proponent of this view in Parliament, as his reply amply demonstrates. But it was a view shared widely across the political spectrum, from the socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan to the liberal stalwart Hriday Nath Kunzru to the executive committee of the Federation of the Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, and including the President of the Republic, Rajendra Prasad.

Beyond the government, few thought that there was an imminent threat to the new nation’s security. ‘Except those in power, no one else in the country seems to be aware of any threat to the security of the state,’ stated Jayaprakash Narayan in May 1951, ‘and yet these crippling amendments are sought to be made in the name of this danger.’ In the case of land reform as well, many doubted the reasons the government trotted out. There was broad and non-partisan consensus in Parliament and outside on the need for land reform. The judiciary had upheld zamindari abolition laws in Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra, confirming that in principle, land reform was perfectly compatible with the right to property. No less than the President advised Nehru that it would be more prudent to bring the legislation into conformity with the Constitution instead of ‘taking the very serious step of amending the Constitution’.

Given these circumstances, many were convinced that far from enabling ‘the true purpose of the Constitution’ as Nehru believed, the amendment was an executive power grab to expand the government’s legal arsenal and augment Nehru’s own power as Prime Minister – a part of an ‘executive struggle and search for constitutional pre-eminence’ conducted in the grey zone before India had its first election and became a functioning democracy. prominent newspaper noted: ‘These [constitutional] changes seem animated more by a desire to conserve and consolidate the power and patronage of the executive vis-à-vis the rights and liberties of the individual.’ Others went further – noting that the amendment demonstrated either India’s unfitness for democratic rule or the inability of its rulers to govern within constitutional bounds.

Also Read: Syama Prasad Mookerjee had pointed out to Nehru his two grand follies

In amending something as central as Fundamental Rights, many believed, Nehru was guided by a partisan political agenda and was, wittingly or unwittingly, laying the constitutional groundwork for potential executive despotism – in the process, creating legal tools and political precedents that could one day be wielded by his ideological opponents. It was this fear – that the expansive notion of republican freedom that the courts had delineated over the previous year could be jeopardized for all time – that led Mookerjee to deliver his prophetic warning: ‘Maybe you will continue for eternity, in the next generation, for generations unborn; that is quite possible. But supposing some other party comes into authority? What is the precedent you are laying down?’

Seventy years on, Nehru’s legal tools, created through the First Amendment and described as his gift to the succeeding generations, have come to be a central focus of political discourse and point of contestation in India. In this renewed contestation over foundational questions, Mookerjee’s arguments are being redeployed by his erstwhile opponents – demonstrating the long afterlife of this debate and the eternally shifting sands of Indian politics.

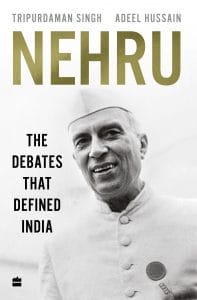

This excerpt from ‘Nehru: The Debates that Defined India’ by Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from ‘Nehru: The Debates that Defined India’ by Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.