A captain and his deputy, Mohammad Azharuddin and Ajay Jadeja, had been enswirled in the fug of corruption. Anointed as successor, Sachin Tendulkar had been unable to provide other than his usual solo excellence. He had been succeeded by Sourav Ganguly, symbolising the steady rise of the game in Bengal since the administrative ascendancy of the local potentate Jagmohan Dalmiya. But a shoulder injury had then incapacitated the linchpin of India’s attack, Anil Kumble, while no wicketkeeper had made himself a fixture since Kiran More.

Then there was the role of coach, held for an unhappy year by Kapil Dev. The appointment of the low-key Wright reflected the desire for a clean break. While coaching Kent in England’s County Championship, he had made the acquaintance of Ganguly and his deputy Rahul Dravid. They warmed to his easy-going ways, and their say-so had helped sway an appointment panel. But he found a team that, while replete with talent, was hidebound in its practices, unfit, unfocused and without the most basic equipment: the kit consisted of three stumps, three baseball mitts and thirty cones. Administration and selection were politicised, intrigue routine.

The visit of the Australians set pulses racing. They had bossed Test cricket for six years, secured the World Cup, virtually owned the Ashes, and overwhelmed India three times at the countries’ last encounter, part of a victory streak that on their arrival extended fifteen Test matches. There was an asterisk against their status: thanks partly to relatively infrequent visits, they had not won a Test series in India since 1969. But they meant business. Their captain, Steve Waugh, who, unlike predecessors, was stimulated by the challenges of the subcontinent, had taken to calling the country ‘the Final Frontier’. When Wright dropped in on their training sessions at Brabourne Stadium, he was awed by its vigour and purpose. He drove his own players harder – as hard as some had been driven. They responded well, but deficiencies were hardly difficult to spot.

The media, seldom less than excited about a cricket visitor, were strung up to concert pitch. A new twenty-four-hour news channel called Aaj Tak (Till Today), the first of its kind, was to pioneer a new approach to cricket, covering it almost as current affairs. Aaj Tak’s news cycle was punctuated with cricket updates and reviews, plus a text graphic of the live score at all times, while its nightly show Who Will Become the World Champion? positioned the Tests as a battle for world supremacy.

The cricket struggled to match such billing. In the First Test at Mumbai, India looked not so much a frontier as a vulnerable principality ripe for annexation. After Waugh sent India in, the taut control of Glenn McGrath, Shane Warne and Jason Gillespie, reinforced by hundreds from Matthew Hayden then Adam Gilchrist, overwhelmed their hosts by ten wickets in less than 250 overs. The team’s dashing young batsman, Ricky Ponting, atoned for failure by compiling a brace of unbeaten hundreds in the ensuing tour game in Delhi, before the team arrived in Kolkata in time for Holi.

So confident were the visitors that Waugh and opener Michael Slater came equipped for celebrations, Waugh with a bottle of Southern Comfort, Slater with a big cigar- although they and four others who had been on the losing side of a Test at Eden Gardens three years earlier took superstitious care not to occupy the same places in their dressing room.

Wright and Ganguly had a great deal more to contemplate. By now, their best fast bowler, Javagal Srinath, had joined Kumble by the wayside. And two of their specialist batsmen arrived below par, Rahul Dravid so stricken with fever that he could not practise, VVS Laxman so in pain from his lower back he needed constant ministrations from physiotherapist Andrew Leipus. Ganguly himself was out of sorts with the bat, and the team’s tail was long and vulnerable.

The mantle of number one slow bowler, moreover, now fell on Harbhajan Singh, a combustible Sikh from Jalandhar who had been expelled for misbehaviour from Bangalore’s National Cricket Academy but recalled to the colours on Kumble’s recommendation. Since his father Sardev had died the year before, Harbhajan’s skinny twenty-year-old shoulders had been bearing a heavy load, including control of the family ball bearing factory and the care of five sisters. He had been challenged by the Australians in Mumbai, broken through early then been collared. Now in his tenth Test he would have to fill both stock and shock roles – and, when Waugh called correctly, on a first day to boot.

Evidence to tea was that the toss had been a decidedly useful one to win, on a pitch finely latticed with cracks but hard as a dancefloor underfoot. The opening partnership of Hayden and Slater was not broken until after lunch, and Hayden’s huge stride and scything sweep menaced the close-in fielders as they had in Mumbai. He had arrived in India with a spotty Test record; having schooled himself in batting on specially dedicated surfaces at Brisbane’s Allan Border Field in preparation for the tour, he seemed almost to have already played the Tests in his mind.

But nothing about this Test was to prove remotely foreordained. Four balls after the interval, Hayden picked out deep backward square leg, falling three runs short of a second consecutive Test century. Approaching the crease in a whirl of long-sleeved arms, relying on overspin and mixing in the occasional seamer, Harbhajan began exerting a measure of control. And when Zaheer Khan had Justin Langer caught at the wicket, the pitch and the environs grew abruptly more hostile.

Steve Waugh would describe Eden Gardens as ‘the Lord’s of India’, such was its heritage and theatre. When it reverberated, it was like listening to the crowd noise amplified through headphones – total, inescapable. As Australia’s captain looked on from the non-striker’s end, Harbhajan now struck four times in the space of four overs, the roar from 75,000 throats never abating. The last three wickets comprised India’s first Test hat-trick, even if the umpiring decisions were of a certainty hard to justify. Ponting was pinned on the crease right enough, but the possibility of an inside edge from Gilchrist and a bump ball from Warne went unentertained by SK Bansal and Sameer Bandekar (the third umpire) respectively. Not that this disturbed the jubilant pile-on of fielders, or the captain, who was inspired to take the ball up himself and win an lbw verdict against Michael Kasprowicz.

It had been a while since Australia had found themselves eight down for as few as 269 anywhere, although they responded with the resourcefulness of a champion team. Waugh, never rushed, as laconic with his strokes as his words, was born for such scenarios. He bunkered coolly down with stiff-armed and soft-handed Gillespie to see the evening out, and they resumed next morning as if performing a toilsome but necessary chore. Bansal evened up his earlier interventions by keeping his finger down when Gillespie nicked Prasad early, but there were no further alarms: their 133-run partnership, Australia’s biggest for the ninth wicket in more than a century, emerged at the jogging pace of three an over, before a final flourish of 43 in forty-nine balls involving Waugh and Glenn McGrath bulked Australia’s total to 445.

After spending five chanceless hours over his first Test century in India, Waugh presented Harbhajan with a seventh wicket by falling to a sweep shot. It would prove the last cause for Indian celebration for more than a day.

With not quite an hour until tea, India were desperate not to lose a wicket: they lost both openers. Two boundaries from Tendulkar stirred the crowd to frenzy; a successful lbw appeal by McGrath stunned them to silence. Having acclimatised painstakingly, Ganguly and Dravid fell four balls apart, beginning a phase of five wickets in twelve overs. The highest scorer was Laxman on 26 not out.

He came in at the close for further maintenance from Leipus; at eight for 128, India seemed beyond treatment. Wright’s night in room 214 was ‘one of the loneliest, most desolate nights of my life’ – that bedraggled exhortation by the three fans was the only note of hope. Otherwise, he could hardly believe the gap that had opened between the sides: ‘The Aussies were an exceptional team, but we were playing as if we didn’t think we belonged on the same park.’

Once his charges are in the field, of course, the impact a coach can have is necessarily limited. But the following morning, Wright had a brainwave that may have changed Indian cricket history. He was fortunate to have the time to make it. At 9/140, Venkatesh Prasad was struck on the full, and India seemed to have been rounded up more than 300 runs in arrears. But Bansal turned the lbw appeal down, and Laxman was able to push on from 37 to 59 with strokes of some panache, confounding Warne by driving him through and over the off side from outside leg stump.

Like someone trying to remember the drift of an old song, Wright recalled something he had once read by Ian Chappell, which recommended the number three role in a batting line-up be held by a strokemaker, to take advantage of attacking fields and dispose of loose deliveries. It was not even half a theory – really just a view. But for want of some other inspiration, and faced with a batting line-up out for 176, 219 and 171 so far in the series, he put the proposition to Ganguly. Dravid’s 73 runs in those innings had taken him almost seven hours. Ganguly agreed that Laxman might be the better bet at first wicket down, and Dravid acquiesced.

Waugh and his coach, John Buchanan, had their own decision to make. Waugh’s predecessor, Mark Taylor, had been a reluctant enforcer of the follow-on, after being thwarted by Pakistan at Rawalpindi, preferring to maximise Warne’s fourth innings opportunities; Waugh was less reticent, confident in his attack’s all-round capacities. India, he now reasoned, was toppling. It was time to administer the coup de grace. Word had reached India’s dressing room by the time Laxman re-entered it. ‘Keep your pads on, Lax,’ Wright said. ‘We want you to bat at number three.’

The tall, twenty-six-year-old Hyderabadi felt disarmingly confident. India had struggled previously to find a role for him. At number six, he had seemed almost an afterthought; at number one, he had felt a little sacrificial. Number three was where he had batted for much of his first-class career, including where he piled up 353 for Hyderabad against Karnataka in the Ranji Trophy semi-final a year earlier. Openers Sadagoppan Ramesh and SS Das now negotiated the dozen overs through to lunch while Leipus continued his task of keeping Laxman supple and pain-free.

Eden Gardens was now officially hot, which the Australians had expected, their hair cut military short, but which constrained their captain from allocating spells too long. The crowd, all those Vinays, Mahmuds and Sanchayitas, somehow never seemed to tire, the atmosphere as unanimous and celebratory as a religious festival. Hearts soared as Laxman took guard after lunch and drove his first ball from McGrath down the ground for four.

The roar echoed again when Das worked Gillespie to fine leg and returned for a second, only to have Gilchrist point out a fallen bail, disturbed by a heel. But somehow the waves of acclamation kept coming, surviving even the disappointment- ment of Tendulkar’s second cheap dismissal in the game just before tea, carrying along the Indians and crashing over the Australians like the breakers on a shore. Every so often Laxman produced a shot that seemed totally out of keeping with the seriousness of negotiating a follow-on: pull shots from the pace bowlers when they attacked him from round the wicket; a cover-drive and an off-drive on the up from Kasprowicz, and finally a nonchalant on-drive from the same bowler that took him to his second half-century of the third day in ninety-three easeful deliveries.

At length, the local boy Ganguly settled in, redoubling the acclaim, winnowing the arrears away to double figures. But the duel of the day, perhaps of the match, was Laxman against Warne. The leg-spinner was not quite at his best. He had missed much of his home summer with a broken finger; he found Kolkata’s heat and airlessness enervating. But he kept whirling away from all angles, probing away at a leg stump rough that occasionally offered extravagant deviation.

It would prove a kind of trap. Laxman was undaunted by deviation; on the contrary, it provided room to manoeuvre, long legs and quick feet extending his sphere of influence. There were on-drives, off-drives, cover-drives, all hit as if from a stationary tee. When Warne then flattened his arc, Laxman laid back and pulled. Although he was within sight of his century when his captain nicked off, Dravid was on hand to help consummate the landmark, calling Laxman through for a quick single from Warne: at 166 balls with seventeen fours, the hundred had been a virtual scamper.

Stumps brought help from reality. The deficit had been reduced to 20 runs, but India held precious little batting in reserve, and the Australian juggernaut had, after sixteen Tests, a certain inevitability about it. ‘It’ll be over tomorrow,’ commentator Tony Greig said airily. ‘More time on the golf course.’ The Australians were of the same mind. Waugh eyed his Southern Comfort thirstily. Slater, who had nursed some reservations about the follow-on, playfully drew his cigar under his nose. ‘This result is so close I can smell it,’ he said, to the amusement of Gilchrist, who had not in his eighteen months as a Test cricketer known defeat.

The Australians bowled that morning as though drawn on by that odour. With a second new ball, McGrath and Kasprowicz hit the deck hard; Gillespie punctured the defences of both Laxman and Dravid, inside edges streaking away for lucky boundaries. Then, when the ball started reversing, Waugh opportunistically turned to Ponting, who wobbled deliveries around at a zesty medium pace – an lbw reprieve granted Dravid caused Australian expressions to darken. But Waugh’s attacking fields ensured that the supply of boundaries was never quite cut off, and with India in credit, each had a context as runs the visitors would have to get themselves. On the stroke of lunch, Dravid reached his first half-century of the series, extending the partnership to 144

Batsmen, bowlers and fielders were now up against the limits of their endurance. Laxman’s back and Dravid’s fever were taking their toll. Teammates cut towels into strips for ice-filled neckerchiefs, which reserve players Hemang Badani and Sarandeep Singh would run out in relays the rest of the day. But after by now more than 160 overs in the field, with only one wicket in the last seventy overs, and four specialist bowlers, it was the Australians running shortest of options.

In the afternoon, Waugh had to turn to his brother’s occasional off-spin, and the seldom-used varieties of Hayden, Slater and Langer, hoping to bring back a key bowler if a wicket fell. None did. Minds were even beginning to wander. Keeper Gilchrist and first slip Warne idled the day listing their ten favourite movies, songs and supermodels. Back in the dressing room, twelfth man Damien Fleming got a glancing view of himself in a mirror and jested ruefully: ‘Good one to miss, Flem. Good one to miss.’

Both batsmen hit boundaries early in the afternoon session to reassert themselves, and Dravid, for the first time, took the lead. His pride had been slightly piqued by his demotion, and the Australians had known it. ‘Three to six,’ they had chirped at him on his arrival the night before. ‘Six to the side.’ He was not about to forget it. Warne had dismissed him seven times. times in Tests already; now Dravid was playing him with ever greater ease, using his feet, then sitting back to enjoy the errors of length. As a cut to the boundary streaked away, Warne bent low from the waist, out of exasperation but as if in supplication. It was one thing for Tendulkar to be his master; now, a whole country seemed ranged against him.

Just after drinks, Dravid passed 86, his previous highest against Australia. There was a new menace now. Although cooled by a fresh neckerchief, he was experiencing painful cramps. Dravid abandoned all thought of the match, the session, even the over. ‘Let me get through this one ball,’ he repeated to himself. ‘Let me get through this one ball.’ But as Leipus came out with a tablet, it was the Australians who looked in greater need of relief: they sat or lay down, squatted and stretched.

Now the milestones were looming ahead. A Dravid flick through mid-wicket raised the double-century stand; a Laxman cover-drive raised his personal double-century. ‘It really has been a masterpiece from VVS Laxman,’ assented Ian Chappell, never one to bestow such tributes lightly, in the commentary box.

On 97, Dravid faced Warne, who theatrically adjusted his field, beckoning and despatching like a dramaturge. Four times, Dravid took his stance only to be kept waiting. At last, he came down the pitch and on-drove his 205th delivery for his thirteenth four to attain his ninth Test century. He waved his bat in circles, then jabbed it meaningfully at the press box – a departure from his usual equanimity that told of the passion of his engagement. By tea, his sangfroid had returned: he walked off a deferential step behind Laxman, while the Australians appreciatively applauded.

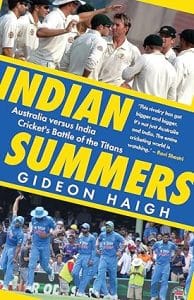

This excerpt from Gideon Haigh’s ‘Indian Summers: Australia versus India – Cricket’s Battle of the Titans’ has been published with permission from Westland Books.

This excerpt from Gideon Haigh’s ‘Indian Summers: Australia versus India – Cricket’s Battle of the Titans’ has been published with permission from Westland Books.