Rukmini Devi possessed a sensibility which enabled her to piece together and rejuvenate a tradition so that it could flow and breathe in open spaces. She empowered tradition with new vigour and potency, making the art communicate to people across cultures, near and distant. She is a prime example of sustaining tradition by conscious modifications, adjustments, recreations and adaptations to remain relevant to the people and the society it serves, for tradition to remain ‘living’.

Modifications also throw up questions about fidelity to the tradition and the art form. Did she Sanskritise Bharatanatyam? A question many have asked. The dance form has always had an association with the Sanskrit treatise on dramaturgy Natyashastra as evidenced by the inscriptions accompanying the sculptures of Karanas in the inner passage of the gopuram (tower) of Brihadeeswara temple built by Raja Raja Chola in the 10th century. There are Natyashastra verses inscribed below the sculptures of dance poses on the walls of the Nataraja temple in Chidambaram too. In an essay on a Dancing Girls, P. Raghiah Chary, writes in 1806 about textual source of gestures of Bharatanatyam and describes their meaning as given in Abhinaya Darpana which Rukmini Devi used on the suggestion of Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai and the post-1960s generation of dance historians saw this as textualization and Sanskritization of the dance form.

The araimandi or the half-sitting position became a mantra for Kalakshetra. Did the Kalakshetra’s insistence on purity of lines go overboard with straight lines, parallel lines and triangles? Did Kalakshetra sanitise the dance in its interpretation of sringara? Did grammar rise over poetry? In the performances of Shantha Rao, Radha Sriram, Mrinalini Sarabhai and Ramgopal, all trained by Rukmini Devi’s guru, the great nattuvanar Meenakshisundaram Pillai, who also designed the curriculum at Kalakshetra, one notices movements that were even sharper than Kalakshetra. Alarmel Valli and Meenakshi Chittaranjan, trained by Chokkalingam Pillai and his son Subbaraya Pillai developed their own unique styles. Successful graduates of Kalakshetra like Shantha and Dhananjayan, Neela and Satyalingam, C.V. Chandrasekhar, Anjali Mehr and Leela Samson have created their own ways of dancing, taking off from the framework and strict training they received in Kalakshetra. Standardisation and sanitization allegations seem baseless today.

A horde of young middle-class girls, inspired by a sprightly and graceful movie star called Kumari Kamala, trained by the iconic nattuvanar Vazhuvoor Ramiah Pillai, flocked to the dance schools of hereditary nattuvanars for Bharatanatyam training. Unfortunately, over time hereditary dancers were relegated to the back seat due to their own patriarchy preferring the men as teachers and bread winners. This interest in learning dance took advantage of Rukmini Devi’s radically redefined training system. This training system was in an institution setting and not individual and family-oriented teacher-pupil setting. Rukmini Devi’s guru Pandanainallur Meenakshisundaram Pillai, who belonged to the Isai Vellalar community and was well-versed in Sanskrit, Telugu and Tamil, designed the curriculum for her, adding to the authenticity and depth of her programme. She gave the task of training students of Kalakshetra to her own graduates led by Sharada Hoffman, N.S. Jayalakshmi and others. Kalakshetra also trained teachers in large numbers who were able to make a career of dance teaching. With the new interest around the world in Indian dance, a great interest in finding the traditional compositions taught in the hereditary style was sought after, particularly by non-Indians and Indians brought up outside the milieu, even if their dance was always informed by their own circumstances of birth, education and influences. A generation removed; the dance did not carry the stigma associated with it anymore.

The Kalakshetra style of dance evolved from Rukmini Devi’s deep involvement with music, love of nature and animals. The ambience created for the art was informed by the designs revived on the saris woven in Kalakshetra and the theosophical idea of respect for all religions. Austere and clean in execution. Her foray into dance productions was informed by the immense exposure she had travelling around the world. That travel urged her to look at authenticity and hence her search for Bhagavatha Mela and her revival and introduction of Kuravanji dance dramas on the modern stage.

Over and beyond this, Rukmini Devi was essentially an institution builder. She treated her institutions not merely as a finite structure with a linear progressive movement. Her insistence was on organic growth.

She revived textiles, she collected great musicians and built a library, making her institution a confluence of many streams of the tradition which had the possibility of revitalisation.

The story of cultural transactions is extremely complex and simplistic assumptions about cultural negotiations are not only anti-intellectual but also turn out to be quite fascistic in their political and academic manifestations. Rukmini Devi drew her intellectual energies from the community around her. She made use of the privileged birth and circumstances that brought her centre stage and the support system that the Theosophical society and her marriage provided her. That she endured great difficulty in creating a dream world for art also meant a deep commitment to the global while she negotiated the local. There was an organic relationship between her and the local community and this brought the joy of dance in all its beauty to the entire globe to celebrate and relish. Her achievements are like a thillanna and the flames of lamps lighting up a deity in a maha-arati in a temple, with all the sounds of the bells and music.

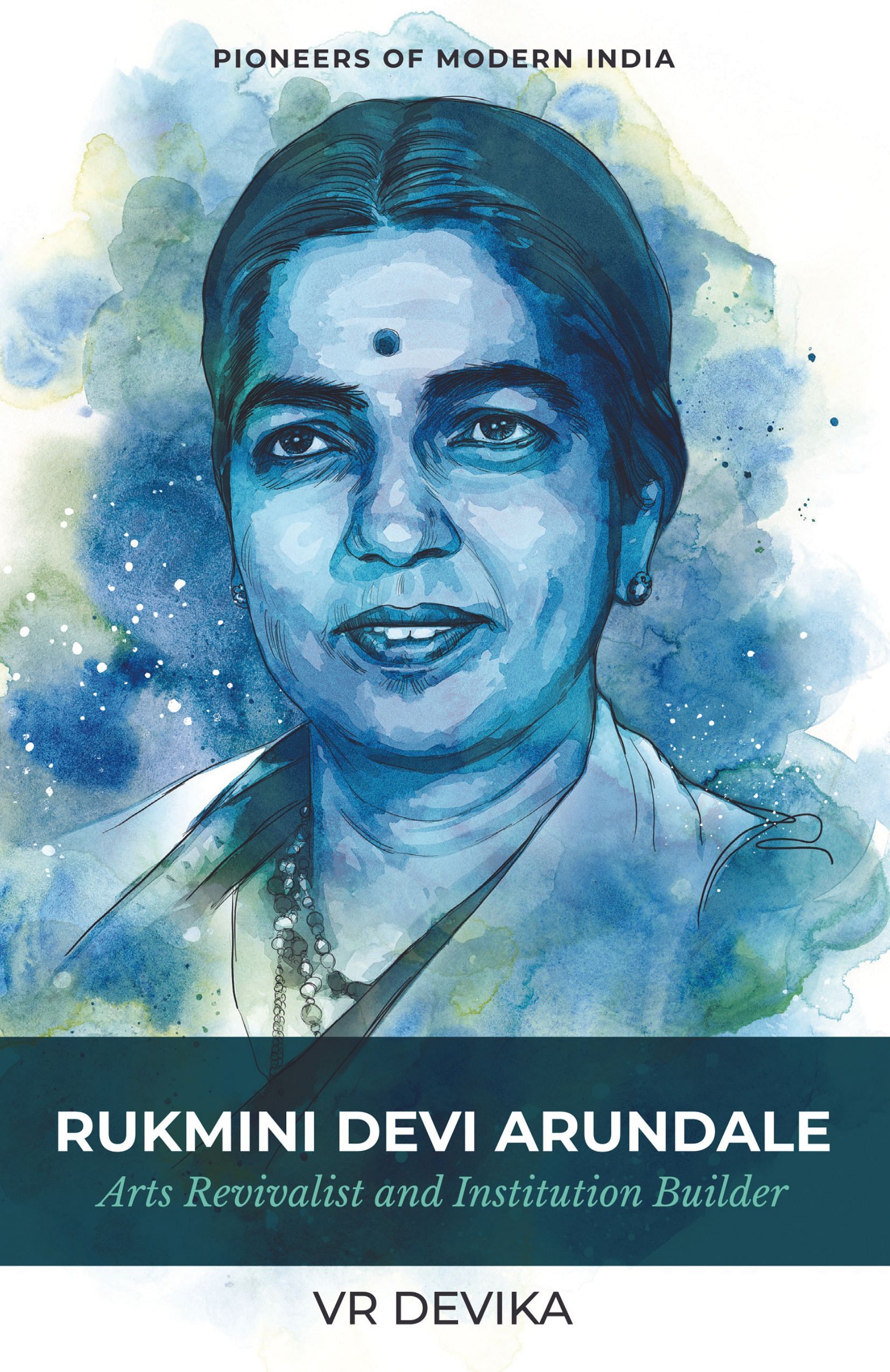

This excerpt from Rukmini Devi Arundale:Arts Revivalist and Institution Builder by VR Devika has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from Rukmini Devi Arundale:Arts Revivalist and Institution Builder by VR Devika has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.