Rajputana was shaped, Susanne Rudolph tells us, by a warrior-ethic, one that “stressed spirit, valor, and abandon.” At one time such a way of being served a great purpose. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, it allowed the clans that would later come to be termed Rajputs to withstand repeated invasions from the northwest. Though compelled to retreat from the rich Gangetic plains to “less inviting country,” namely the arid, hilly region that would later be known as Rajputana, the martial habits of these clans preserved them from oblivion. Over the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the same habits then allowed the ablest of them to establish principalities, the most important of which grew to be Mewar (later Udaipur), Marwar (later Jodhpur), and Amber (later Jaipur).

This difficult birth granted the Rajputs, as K. R. Qanungo memorably put it, “the best of pedigrees—the sword.” It would have remained a commendable parentage had the Rajputs been able to transcend their clannish origins. But unfortunately, from the outset this community displayed an unerring tendency to be “split up” by “archaic wrangling” over points of honor. And once they had drawn their swords, Rajputs struggled to sheathe them, because they made vair (vendetta) the “salt of life.” As a result, the “gratification of revenge” became something like “a moral obligation,” pitting clan against clan, family against family, leading ultimately to an “interminable course of feuds.”

Such a culture, Rudolph notes, was never going to be “hospitable to successful statesmanship.” What preserved the Rajputs was sheer grit marshalled by meteoric personalities. Thus, the Delhi Sultanate, which dominated North India between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, was ever “plundering and slaying” in Rajputana, but it was not able to make a “serious impression” on the hardy inhabitants of this “difficult land.” And when the Delhi Sultanate began to decline, the Rajputs even formed a confederacy under Rana Sanga of Mewar who, at the cost of an eye, two limbs, and some ninety scars, obtained something like hegemony over his fellow chieftains. But the enterprise was fragile. In 1526, Uzbeks led by Babur marched in from the northwest. The confederacy, led by Sanga, met them at Khanwa where Rajputana’s “mounted splendor” was outmatched by the Uzbek’s “furious artillery.” At this critical moment, instead of regrouping, the Rajputs splintered, with Sanga apparently poisoned by dissenting clans who “had no desire to renew conflict.”

Upon gaining control of Northern India, Babur’s descendants, now better known as the Mughals, made it their mission to subjugate Rajputana, lest its inhabitants emerge from their desert strongholds at inopportune moments. The Rajputs helped the process along by once again failing to unite. When Babur’s grandson, Akbar, invaded Rajputana in 1561, the Kachwahas of Amber, then a relatively minor clan, submitted “at once.” The Rathores of Marwar put up a fight, but alone could not resist the Mughals’ by-now “colossal power.” In the end, both clans “purchased peace” by surrendering a daughter to Akbar’s teeming harem, opening the door to profitable imperial service. The Sisodias of Mewar, though unprepared for the contest, refused to surrender, for which reason they were brutalized. Akbar penetrated Mewar’s fortresses and massacred tens of thousands of innocent civilians, prompting the ruling family to retreat to the hills. There they remained until Rana Pratap, the “savior of his race,” ascended to the throne

in 1572 and launched a grueling campaign to eject the Mughals. To underscore that they alone had not bartered a daughter to obtain clemency and crumbs, the Sisodias henceforth refused to intermarry or even dine with the “effete” Kachwahas and Rathores. But one man can only do so much. Rana Pratap died in 1597. Within a decade, Akbar’s son, the emperor Jahangir, dispatched his forces to Mewar and, as the Kachwahas and Rathores docilely looked on, obtained its submission. The Sisodias were not, however, compelled to hand over a daughter, a “concession” that maintained their distinctive status amongst Rajputs.

By the end of the seventeenth century the Rajputs appeared to have learned their lesson when the fanaticism of Akbar’s great-grandson, Aurangzeb, persuaded them to sink their “petty enmities” and unite “for a greater cause,” namely, to preserve their ancestral religion and secure mutual protection against “capricious abuses.” The rising tide of rebellion, led by Jodhpur and Udaipur, left Mughal forces harried and worn. Later, even Jaipur, which had obtained preeminence in Rajputana by serving the Mughals, began to buck. In 1700 the three kingdoms even managed to form a “triple alliance,” harkening back to Rana Sanga’s stand against Babur. So unified, the Rajputs met with success, expelling the Mughals from their lands during chaos that followed Aurangzeb’s death in 1707. But when the Mughals regrouped and returned to the region in the following decade, the triple alliance gave way. Jaipur, greedy as ever, defected to resume imperial service, leaving Jodhpur and Udaipur, by now shadows of what they once were, to brood in cold silence.

Over the next two decades, as the Mughal empire went into terminal decline, the balance of power shifted in favor of its vassals, which began to exercise independent control over territories they had previously governed on behalf of the suzerain. But barely had the Rajputs begun to assert themselves in Central India than the Marathas, the rising power in the Deccan, appeared on the scene. As they moved upwards, compelling the Mughals to surrender to them the right to exact tribute from ever-wider swathes of territory, the Marathas turned their eyes toward Rajputana. They recognized that the region’s wealthy commercial centers, strategically located forts, and battle-hardened clans could bolster their growing empire. But the Rajputs, with their high opinion of themselves, and still relishing with their newly regained freedom, were not keen to be reduced to mere tributaries. Thus began a prolonged contest over the terms of submission. Unfortunately, to extract the best possible terms the Rajputs would need the skill they possessed least—the ability to act in concert.

The Marathas did not find it difficult to insert themselves into the picture. In 1743 Sawai Jai Singh, the Maharaja of Jaipur, passed away whereupon his sons, Ishwari and Madho, fell out over which of them was entitled to succeed. Ironically, this dispute originated in the terms of the aforementioned triple alliance forged against Aurangzeb, which had readmitted Jaipur and Jodhpur to “the honor of matrimonial connection” with Udaipur on the condition that the sons of Udaipur princesses would have precedence in the line of succession. On this basis, Madho, born to an Udaipur princess, laid claim to the Jaipur throne, whereas Ishwari, being elder, insisted on the sanctity of primogeniture. Unable to prevail, both sides sought aid from the Marathas, who had by now seized control of neighboring Malwa. This was par for the course, as the Rajputs had previously permitted the Mughals to settle their disputes. But the Mughals were a monarchy, whereas the Marathas were a confederacy. So where once there had been an appeal to an emperor, now there was an appeal to many sardars (chieftains), each of whom was hoping to build up a kingdom of his own.

Subsequent proceedings in Jaipur signaled what was to come. Madho offered Malhar Holkar, the leading Maratha sardar in Malwa, 2 lakh rupees to support him in battle. Ishwari countered by offering more to Holkar’s fellow sardar, Ranoji Sindhia. Udaipur, which championed Madho as he was the son of an Udaipur princess, then upped the ante by offering 10 lakhs to the Peshwa, the head of the Maratha Empire, who ordered Sindhia to join Holkar. So combined, the sardars easily humbled Ishwari, from whom they then demanded 50 lakh rupees in indemnities. Unable to raise even half the sum, Ishwari made sure to commit suicide by swallowing arsenic, then inducing a bite from a cobra, and perhaps also ingesting gold dust. His rival did not feel much better. After placing Madho on the throne, Sindhia and Holkar proposed that he grant them “one- third or at least one-fourth” of Jaipur’s territory. Angered by the sardars’ “insatiable greed,” Madho responded by trying to murder them. His plots failed but an orchestrated riot led to the massacre of some 1500 Maratha soldiers, an affront that the sardars only forgave after being promised 75 lakhs in cumulative tribute.

So matters went for the next half century. The Marathas “became the general referees in all disputes” in Rajputana, which they usually “decided in favor of the highest bidder.” A succession dispute in Jodhpur, for instance, yielded more than 50 lakh rupees, while one in Udaipur netted them about 65 lakhs.The Rajputs responded to such fleecing by invariably paying less than they had promised. This tactic eventually prompted the Marathas to seize valuable territories as sureties, which only exacerbated the harm done to the exchequer. For instance, when the previously mentioned Madho of Jaipur delivered up less than half of the 75 lakh rupees he had promised, he had to suffer a show of force, which ended with Holkar marching away with a 36-year lease on Rampura, a region yielding 3 lakhs in annual revenue.

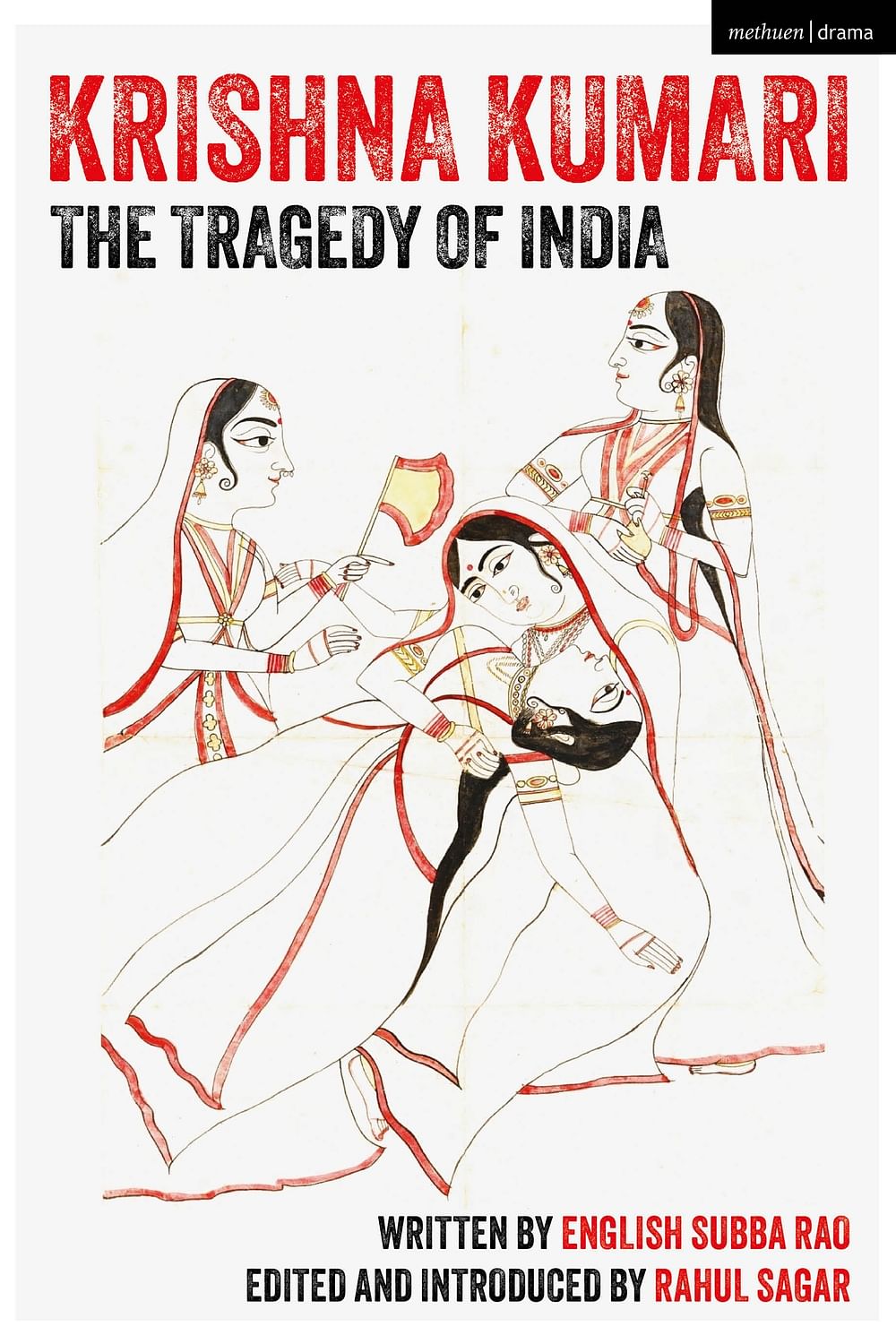

This excerpt from Krishna Kumari: The Tragedy of India written by English Subba Rao and edited and introduced by Rahul Sagar has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

This excerpt from Krishna Kumari: The Tragedy of India written by English Subba Rao and edited and introduced by Rahul Sagar has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

The Rajputs were not statesmen…because they didn’t want to negotiate with agressors of the Bharat. Though they had individual kingdoms, they viewed Bharat as a whole. An analogy is seen current India . While all opposition parties want to have dialogue with Pakistan, Modi government says unequivocally, we will talk until there is zero terror.