I don’t believe it was an accident that I took center stage at Rajaratnam’s trial. In fact, the series of events leading up to it left me fairly certain that it was part of a deliberate campaign on the part of the Justice Department to try me and find me guilty in the court of public opinion. Preet Bharara, the ambitious US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, was itching to charge me—I could feel it. I wasn’t a banker, but I was of sufficient stature that maybe the public wouldn’t notice the mismatch. However, with only the thinnest circumstantial case against me, he needed to ensure that the jury pool was primed to judge me harshly.

One question to which I—and many others—have given a great deal of thought is this: Why did the SEC scramble to file charges against me just days before the Rajaratnam trial, allowing no time to review my detailed response to the Wells Notice? I’ve reflected on this question at great length, as did the press and anyone else observing the case. Writing in the New York Times, the financial journalist Andrew Ross Sorkin commented, “there is something curious about the accusations against Mr. Gupta, which came just days before Mr. Rajaratnam’s criminal trial . . . . Given the seriousness of the claims— insider trading by an executive who had reached the upper echelons of corporate America—why not bring criminal charges against Mr. Gupta?” However, he noted that the evidence, such as it was, seemed barely enough to warrant even the civil charges, with the SEC only claiming that it was “very likely” I had spoken to Raj on the days in question. “Since when has ‘very likely’ been considered enough to make a civil allegation?”

Personally, I felt that this smacked of a collaboration of sorts between the Justice Department and the SEC. Surely, Bharara knew he didn’t have enough evidence to press criminal charges, but the SEC charge was an “administrative” one, which carried a much lower standard of evidence than the federal court. Perhaps getting the SEC to charge me was another step in the PR campaign to set the stage for him to do so when the time was right. These charges would solidify the image of my guilt that had been planted in the public mind by the leaked article, and give the US Attorney’s Office (USAO) more time to build a case.

Also read: Indian CEOs and rich IITians are giving Rajat Gupta a second chance

I’ll likely never know if my theory is true, but it seems consistent with Bharara’s playbook. An ambitious Indian immigrant who had moved to the US with his parents at the age of two, Bharara took office in 2009. I had personally never met him, but as I struggled to come to grips with the invisible chess game, I quickly realized that this was someone I needed to understand. When I began to read up on his tenure as US Attorney and the tactics he employed to succeed, much of my own experience began to make more sense.

Bharara’s appointment had initially inspired high hopes that he would aggressively pursue charges against the banking executives responsible for the financial crisis. No such charges were forthcoming, however, and soon he became the target of pointed criticisms in the press. The public was angry, and rightly so. The bankers seemed impervious to prosecution, the banks were getting government bailouts, and ordinary, hard-working people were losing their homes. Bharara must have needed a new story. If going after the big banking executives was too difficult, he needed another way to appease the public’s desire for convictions. Hedge funds were an ideal target—the “next best crooks,” as New York magazine put it. They carried the aura of Wall Street greed and excess, but were not enmeshed in the global financial markets or in politics the way the big banks were. They also lacked the political muscle to defend themselves. It was a shrewd strategy: by cracking down on insider trading and aggressively prosecuting hedge fund managers and their informants, Bharara could appear to be taking a hard line on corruption without actually pursuing the tough cases and endangering his perfect record of convictions (a strategy that led former FBI director James Comey to dub Bharara and his colleagues “the chickenshit club”).

To ensure the success of his strategy, Bharara seems to have done what any good politician does: he hired PR people, lots of them. Press conferences, press releases, dramatic predawn arrests, perp walks for the cameras, well-publicized speeches, and TV appearances became the norm. Bharara was a natural performer, shifting between self-deprecating humor and rather pompous moralizing. Following each arrest, he invited the cameras in and fed reporters carefully prepared soundbites (“Greed, sometimes, is not good,” he told the press after Rajaratnam’s arrest, declaring that the case should be “a wake up call for Wall Street.”).

Also read: How racist Indians accused American Preet Bharara of selling out & serving ‘White masters’

Bharara also became known for his habit of writing lengthy complaints against his targets, exhaustively detailing the allegations against each defendant. Reputations were destroyed long before cases reached the courtroom, and indeed many never got there. Feeling powerless to fight the government’s narrative, which the press eagerly picked up and disseminated, most defendants of the era chose to settle out of court and pay hefty fines. Much later, in 2015, a district judge would strongly rebuke Bharara for these tactics, noting that “criminal cases should be tried in the courtroom and not in the press.” She criticized the government’s “brinksmanship relative to the Defendant’s fair trial rights,” the USAO’s orchestrated “media blitz,” the questionable timing of some of his arrests, and his tendency to “bundle together unproven allegations regarding the defendant with broader commentary on corruption” in his public statements. All these were tactics he had practiced in previous cases, and many of them showed up in mine.

In 2009 Bharara’s playbook had not drawn much scrutiny, and the moment my name came up in the Rajaratnam investigation, he must have seen an opportunity. A high-profile global businessman with close ties to the titans of industry and politics—that would look very good on his résumé. That I, like many of those he targeted, was a fellow Indian only served to burnish his tough-guy aura. There was just one problem in my case: he had little if any evidence to go on. I imagine this irritated him—he once described to an interviewer the frustration when “you have a belief that somebody has committed a crime and you just can’t get the evidence because no one has flipped or because there are no recordings . . .” He kept digging, but he also began his parallel offensive, setting out to ensure that by the time I was actually tried everyone would already believe I’d committed the crime. On May 11, 2011, Rajaratnam was found guilty on all five counts of conspiracy to commit securities fraud and nine counts of securities fraud. Even in his closing argument against the defendant, prosecutor Reed Brodsky still seemed to be making a case against me. “You don’t get on the board of Goldman Sachs without having accomplished a lot in your life and having a great reputation,” he declared. “Having a great reputation doesn’t give you a free pass to violate the law. Nobody is above the law, no matter how good their reputation is.”

As I read the press coverage of the verdict, I could not shake the growing sense that I too had already been found guilty, although I had been neither charged nor tried. Even my usually sanguine legal team was somber. No one was telling me not to worry any more, not even Gary. Instead, he told me, “We need to prepare to defend a criminal case.”

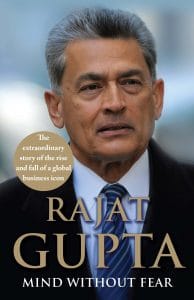

This excerpt from Mind Without Fear by Rajat Gupta has been published with permission from Juggernaut. Paperback Rs 699.

This excerpt from Mind Without Fear by Rajat Gupta has been published with permission from Juggernaut. Paperback Rs 699.