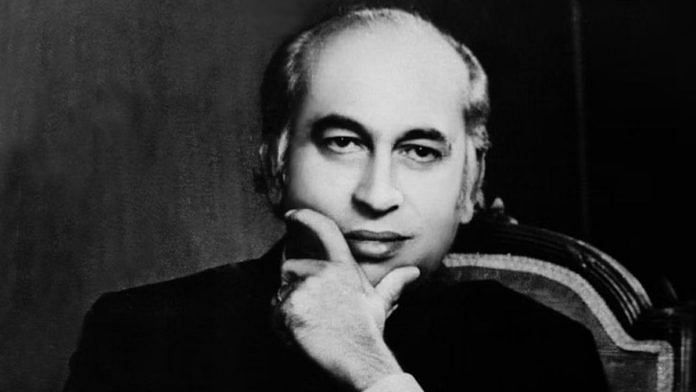

On 20 January 1972, within a month of Lt Gen. Niazi’s inglorious surrender, Bhutto called all the eminent physicists and scientists in Pakistan to convene in Multan under a shamiana, or multi-coloured tent, pitched in the lush gardens of the home of Nawab Sadiq Hussain Qureshi, a wealthy landlord and close friend of Bhutto. This meeting brought together Pakistan’s scientific elite to discuss how to make a nuclear bomb. A year later, Qureshi would be appointed as the chief minister of Punjab. A key invitee to the meeting in Multan was Ghulam Ishaq Khan. In an inspiring speech, Bhutto captivated his audience. He stressed on avenging Pakistan’s humiliation. He wanted to take Pakistan nuclear.

None of the old guards among the scientists inspired Bhutto with any confidence that they would be able to give him the nuclear bomb. However, three young men stood out in the group of scientists that January. One was Dr Samar Mubarakmand, a young scientist who would be a key figure in Pakistan’s overt nuclear test twenty-six years later.

Another young scientist was Munir Ahmed Khan, who had just returned from Vienna after spending seven years with the IAEA.

He was uniquely equipped with invaluable knowledge of how to circumvent the global nuclear proliferation policing regime. He would soon replace the then chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC), Dr Ishrat Usmani. A third key figure was Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmood, who would be famously named thirty-one years later in 2003 by US President George W. Bush as the man who promised Osama bin Laden that he would provide al-Qaeda with nuclear devices.

Bhutto soon brought the meeting to a close. He had decided to tap the Muslim Brotherhood in the Arab world for funds. Pakistan was a defeated nation tottering on the verge of bankruptcy. That same day, Bhutto left on a whirlwind tour of Libya, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, Abu Dhabi, Dubai and other Arab nations. His last port of call was China. Bhutto went hat in hand looking for coppers to fill his coffers with so that he could embark upon his nuclear quest. Out of all the leaders he met, two responded with warmth and empathy towards another ‘brown Muslim’ whom they felt ought to be helped. These were Muammar Gaddafi of Libya and Sheikh Zayed Al-Nahyan of Abu Dhabi. The latter was also the first president of the newly minted United Arab Emirates, or UAE.

Bhutto’s fellow traveller on this tour was Ghulam Ishaq Khan, whose role was to establish contact with the top-ranking financial minister/official in each of these countries.

Abu Dhabi was the largest and wealthiest member of the UAE, an oil-rich federation of sheikhdoms formed in 1971, whose constituent rulers had absolute ownership of all the land and natural resources of their nations with no distinctions being made among the wealth of the ruler, the wealth of his family and the wealth of the nation itself. Sheikh Zayed of Abu Dhabi was installed as the head of the newly wealthy oil kingdom of Abu Dhabi after a British-led coup against his brother in 1966. It was here that Bhutto and Ishaq Khan struck gold, so to speak.

On his return to Islamabad from his whirlwind tour, Bhutto embarked upon a nationalisation spree of certain industries and businesses in Pakistan. All commercial banks were nationalised. One victim of nationalisation was UBL. Abedi was placed under house arrest on the grounds that he was routing non-performing loans to the Saigol Group, the majority owners of UBL. This charge was unfair because only sometime earlier had Abedi been resisting granting loans to the Saigol Group companies, and the promoters were trying to oust him as CEO of UBL. It was Ishaq Khan who came to his rescue at that time.

Once again, in March 1972, Ishaq Khan thought about Abedi and his capabilities. Sheikh Zayed had made a return trip to Islamabad. Abu Dhabi was willing to support Pakistan in creating a financial vehicle that would ostensibly be private and at arm’s length from the governments of both Pakistan and Abu Dhabi. In reality, it would be secretly controlled by both governments but run by Pakistan. It would be built on the fiction that it was heavily capitalised by oil-rich Arab leaders, while the reality was that all of them would only be acting as nominees, providing either only their names to the proposed entity or their names plus funds in the form of deposits to get a guaranteed no-risk return rather than fund the bank as actual investors at risk.

Who could head such an institution and successfully run it through a web of deception and deceit? Who could spread authentic-sounding disinformation about the true intentions of such an entity? One name stood out repeatedly. It was that of Abedi. Ishaq Khan had lengthy chats with Awan, who too endorsed Abedi’s name. Finally, the job was to convince Bhutto and have Abedi released from detention. Abedi, it is said, jumped at the idea of realising his dream of becoming a major player in global banking. But first, according to Awan, an international profile had to be built for Abedi, who had to be seen as wooing Sheikh Zayed. Awan was of the view that it was imperative for Abedi to appear credible as well as distant from the government of Pakistan.

And most of all, Abedi had to be implicitly trusted by the Arabs. Hunting with trained falcons had long been a traditional sport amongst all wealthy Arabs in the Gulf. Awan came up with the idea of organising a programme in which Arab falcons could be brought to Baluchistan to hunt the houbara bustard there. Abedi would be the host. Between 1967 and 1972, Arab royalty, including such notables as Sheikh Zayed of Abu Dhabi, Prince Bandar bin Mohammed Al-Saud of Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Khalid of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Rashid of Dubai and Crown Prince Fahd of Saudi Arabia, regularly visited Rajasthan in India for this sport. The falcons they brought for this had killed 2,400 rare Indian bustards. There were only 1,000 bustards left in India, and then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government banned the sport. In fact, Sheikh Zayed’s 1972 visit to Pakistan kicked off the sport in that country and made it an annual affair.

It is still unclear and probably will remain forever unclear as to what covenants Abedi had executed in secret with the Pakistan government that permitted him to establish and independently run BCCI and also aggrandise himself with untold wealth in the process. Apart from Sheikh Zayed’s help, the enterprise needed credibility in order to crash into the world of global banking, which was still a White man’s club. Abedi had only one contact he could use to crash into this exclusive club. That was a Dutchman named Dick van Oenen, who ran Bank of America’s (Bank Am) representative office in Karachi during the time that Abedi ran UBL. Coincidentally, both had offices in the same building. It is unclear what incentives Abedi offered Van Oenen, but right after he had secured his release from house arrest, Abedi flew with Van Oenen to San Francisco for a lunch meeting with Bank Am’s legendary chairman A.W. ‘Tom’ Clausen.

The wily Abedi literally promised Clausen the keys to the kingdom of Abu Dhabi and beyond it, to introductions to members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). What resulted brings to mind Lord Acton’s saying ‘greed corrupts and absolute greed corrupts absolutely’. Clausen agreed to invest $625,000 for a 30 per cent equity stake in BCCI and a seat on its board. Abedi now had his bank in place. Abu Dhabi was the other provider of capital for BCCI. It was BCCI’s largest depositor and borrower, and for most of BCCI’s existence, its largest shareholder. The relationship between the two entities was, as the famous accounting and audit firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) told the Bank of England (BoE) days before BCCI’s closure, ‘very close’, with BCCI providing services to the ruling family of Abu Dhabi far beyond what an ordinary relationship between a bank and its shareholders or depositors entailed.

The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, holder of a 10 per cent interest in BCCI beginning in 1980, appears to have made some cash payments for its interest in BCCI, which had a book value of approximately $250 million as of 31 December 1989. An unknown but substantial percentage of the shares acquired by Abu Dhabi overall in BCCI appears to have been acquired on a risk-free basis – either with guaranteed rates of return, buy-back arrangements or both.

As a result, BCCI never had a substantial capital base and was forced from the beginning to use deposits to meet its operating expenses rather than to properly invest capital in extending legitimate loans or other financing. Not having an actual capital base, BCCI simply pretended it had one and relied on the reputation of its shareholders to assist it in doing so in order to lure others to deposit their funds with it. As BCCI officers later revealed, the bank in effect had to create retained capital out of its operating profits by juggling its books because of the lack of real capitalisation. And because there were not real profits either, the supposed profits too had to be manufactured by means of juggling the books pertaining to deposits. These deposits, in turn, could only be given a good return on investment by means of using the funds from new deposits, requiring BCCI to grow at a frenzied pace in order to avoid collapse. It was a classic Ponzi scheme designed to finance Pakistan’s clandestine nuclear programme.

In 1972, Bhutto, now prime minister, devalued the Pakistani rupee by 131 per cent. This had a collateral benefit in that it buttressed Abedi’s image as an entrepreneurial Pakistani relocating overseas and starting a new banking business far from the clutches of the ‘Islamic socialism’ practised by the Bhutto government in Pakistan.

In September 1972, at the five-star Phoenicia hotel in pre-Yom Kippur–war Beirut, Abedi launched his new venture, the BCCI. The bank was launched in the Phoenicia’s ballroom in the presence of a group of a hundred Pakistani Muhajirs, or refugees, like Abedi himself, who had their roots in north- central India. BCCI S.A. (owned directly by its shareholders) was incorporated in Luxembourg. In a matter of eight quick months, Bhutto had his financial structure in place to pursue his dream of going nuclear. However, by 18 May 1974, when India detonated its first nuclear device at Pokhran in the Rajasthan desert, nothing had been achieved on the nuclear front in Pakistan. The PAEC had drawn a blank in going down the plutonium route and was engaged in circular arguments with the international community over the terms for the purchase of a French reprocessing plant.

During this period, an India-born Pakistani Muhajir called Abdul Qadir Khan, or A.Q. Khan, was writing letters to Bhutto, wishing to share his nuclear knowledge with the Pakistani government. In August 1974, after having him vetted by the ISI, Bhutto sent for Khan. He was born in Bhopal in 1936 and migrated to Pakistan in 1952. From there, Khan made his way to Holland (the Netherlands) in 1961, where he finally obtained his Ph.D in metallurgy from the University of Leuven in Flanders in 1971. Following his doctorate, Khan got a job at FDO, a Dutch engineering firm. FDO supplied parts and expertise to Ultra Centrifuge Nederland (UCN), the Dutch partner in the uranium-enriching British-Dutch-German consortium URENCO. UCN’s plant at Almelo in Holland was running one of the most secretive projects in Europe.

The existing uranium enrichment technology based on diffusion was very expensive and complicated. The scientists at Almelo had developed a unique and very cost-effective yet highly efficient uranium enrichment process for gravitational or centrifuge separation of uranium isotopes. Through this process, if enriched uranium was passed through an entire cascade of interconnected centrifuges, it would eventually be enriched further, possibly to the critical mass needed for a nuclear device.

In December 1974, Khan, his Dutch–South African wife and their two daughters arrived in Islamabad for the Christmas holidays. Khan had a meeting with Bhutto and patiently explained how superior and cost-effective centrifuge technology was over the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission’s plutonium programme. Khan’s back-of-the-envelope calculations showed Bhutto that each bomb typically required 15 kilograms of highly enriched uranium and that this would cost only $60,000 to manufacture. The icing on the cake was the discovery of a vein in the foothills of Pakistan’s Suleiman Mountains range in 1963; the country was found to have an enormous stockpile of uranium ore. Bhutto sent Khan back to Holland to collect all the data on the breakthroughs made in Germany on centrifuge design and simultaneously instructed Munir Khan to begin research on building a uranium enrichment plant.

Meanwhile, any such operation involving large-scale smuggling of technology and equipment also required an efficient logistics network. Three brothers – Abbas, Mustafa and Murtaza Gokal – had set up the Gulf Group (officially Gulf International Holdings) in Karachi. In 1969, they started Gulf Shipping Lines, the flagship company of the Gulf business group. Gulf Shipping Lines was registered and headquartered in Geneva. By 1975, the brothers were in charge of a fleet of at least 240 ships, ninety-seven of which were owned and the rest chartered. They distinguished themselves in the shipping world and began to be accepted.

However, they were not averse to breaking the law, and there is a reported case of 1983 where they attempted to bribe a British captain of a chartered cargo vessel to ‘falsify his log book’. The captain would not be bribed, but he discovered that his signature had been forged and that duplicate documents that altered the original entries in his log book had been filed with the necessary authorities. For all clandestine trade, the Gokal brothers used their Swiss company called Tradinaft. It is reported that the Gokals were involved in a highly secretive BCCI deal that bankrolled a consortium made up of Libya, Pakistan and Argentina in its quest for nuclear weapons.

By 1976, the Gokals were borrowing heavily from BCCI for reasons best known to them and to Abedi. By 1978, the brothers were in financial trouble and BCCI loans weren’t being repaid. BCCI continued lending to them anyway. To make it appear that the Gokals were repaying their loans, audit reports showed that BCCI applied unrecorded deposits – other people’s money – to their account. It also created phoney loan accounts in the names of other Middle Eastern investors and drew money from there. Money was shifted among BCCI’s lightly regulated affiliates. Sometimes the bank simply faked the paperwork to assist the Gokals. Gulf Group created seventy-one shell companies to which BCCI made ‘loan after loan after loan’ as Masihur Rahman, BCCI’s former chief financial officer, testified before a 1991 US Senate subcommittee investigating the BCCI case, despite what he called threats to his life.

Although the bank started as BCCI S.A., within a couple of years, Abedi decided to restructure it. A holding company called BCCI Holdings was created. And the bank underlying it, BCCI S.A., was split into two parts: one with its head office in Luxembourg, called BCCI S.A., and the other with its head office in Grand Cayman, the largest of the three Cayman Islands, which constitute a British Overseas Territory and are also a well-known tax haven. The BCCI S.A. bank mostly had its presence in European and Middle Eastern locations, and BCCI Overseas Bank was mostly present in Third World countries.

In this manner, Bhutto was putting together the ingredients necessary to build the Pakistani nuclear bomb. Since Bhutto himself was short on scruples, the entire process of bomb building that he orchestrated was cloaked in deception and illegality from the point of view of international law. But to Bhutto, this was needed to make Pakistan realise its destiny.

This excerpt from Iqbal Chand Malhotra’s ‘The Bomb, The Bank, The Mullah and The Poppies’ has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

This excerpt from Iqbal Chand Malhotra’s ‘The Bomb, The Bank, The Mullah and The Poppies’ has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.