While I have had numerous breakfasts at MTR, writing this essay was the perfect excuse for another one. I compared notes with my father and realized that the experience is by and large the same. Walking up the few concrete steps to MTR’s double door is like crossing the threshold into another period. Along the wall to your right is a bench for those waiting their turn. Over the bench are the many framed awards that MTR has been bestowed with over the years.

The cashier at the counter signals us, in the middle of his many ongoing transactions, to make our way upstairs to be seated. On the way, you see wooden panels of framed black and white photographs of famous personalities who have dined at MTR and of events the restaurant has catered. These frames are all over the many dining rooms across the upper floor of the restaurant. If you end up in the waiting area at the top of the staircase, there are large frames displaying multiple photographs—like one of the tenth anniversary of the Chamber of Commerce, Bangalore City, that MTR catered on 19 December 1946.

Once seated on the signature red plastic chairs, you either know what you want to order or you ask for the day’s menu. It will be recited, beginning with their popular dishes, and if you still haven’t ordered through the recital, then the rest of the menu. For breakfast that day, we started with the kesari bath. The version here is a mix of both semolina and vermicelli and is not cloyingly sweet. Studded with raisins and made in generous amounts of ghee, it sets the right tone for the rest of the meal. Next up was the rava idli, a MTR creation that harks back to World War II and speaks to Yagnappa’s ingenuity. Idlis, which are a highlight of their menu, are made from rice. However, during World War II, Japan invaded Burma, the largest producer of rice in the region and the chief supplier to South India. Naturally, this caused a shortage, and MTR was among the many affected eateries.

Yagnappa experimented with rava (semolina), soaking it in curd, mixing in curry leaves and coriander, giving it a tempering of mustard seeds and cashew nuts in ghee, and then steaming it as one would a regular idli. The result was a fluffy, lighter idli that people couldn’t get enough of long after the war was over. On our table that day, it came with a small steel container of molten ghee to pour over it and some chutney and sagu (a vegetable curry).

Those were not his only innovations. After his Europe sojourn, Yagnappa created the chandrahara. This pastry-like dessert consists of layers of flour that are deep-fried to a biscuity goodness and then topped with a sweet, thick sauce made from khoya. Available only on Sundays, this sweet was initially called ‘French sweet’, but it didn’t catch the interest of diners. That was until Yagnappa renamed it chandrahara after a hit film that was playing at a theatre nearby. People couldn’t get enough of it. I tried looking up this movie, and while I didn’t find a Chandrahara from that time there was N. T. Rama Rao’s Chandraharam released in 1954.

Yagnappa also came up with the French fruit mixture with American ice cream, a dish which is still served. ‘We have no clue why he called it that, but this Europe trip must have been inspiring,’ Hemamalini tells me, pointing out that even the word tiffin in the establishment’s name was a British term. ‘He did things his own way, and people took to it because it was so different,’ she adds.

‘In my grand-uncle’s time, once the restaurant closed for the day around 7.30 p.m., we had dinner parties for around 100 people. These took place about three times a week,’ she tells me, adding that these were forty-course dinners with seven types of sweets, appetizers, and main courses. And the amazing part? It was a sit-down service!

Coming back to our breakfast, two dosas came to the table. One was the pudi dosa—a thick open dosa with a blob of potato bhaji in its centre and smeared generously with pudi (powdered lentils and chilli that is added over a dosa with a layer of ghee to help spread it). The other was the classic MTR masala dosa—a well-roasted triangle which hides the bhaji. Both are served with a little container of ghee on the side. Accompaniments of chutney and sambar completed the dishes, and there was silence at the table till we were done eating. A filter coffee that is finished with some frothy milk foam on top signalled the end of breakfast.

Their filter coffee played a huge role in MTR’s legacy. It was a beverage that spurred conversations among freedom fighters, businessmen, and more. Yagnappa’s dedication to perfecting the brew was unparalleled. He would painstakingly select, roast, and grind beans every day to ensure he achieved the flavour he wanted. He used buffalo milk to enhance the taste. Back then, the coffee was served in silver cups with a precise quarter inch of froth on top. That froth we were sipping truly had a story behind it, and Hemamalini recounted how the family worked hard on preserving the integrity of their coffee.

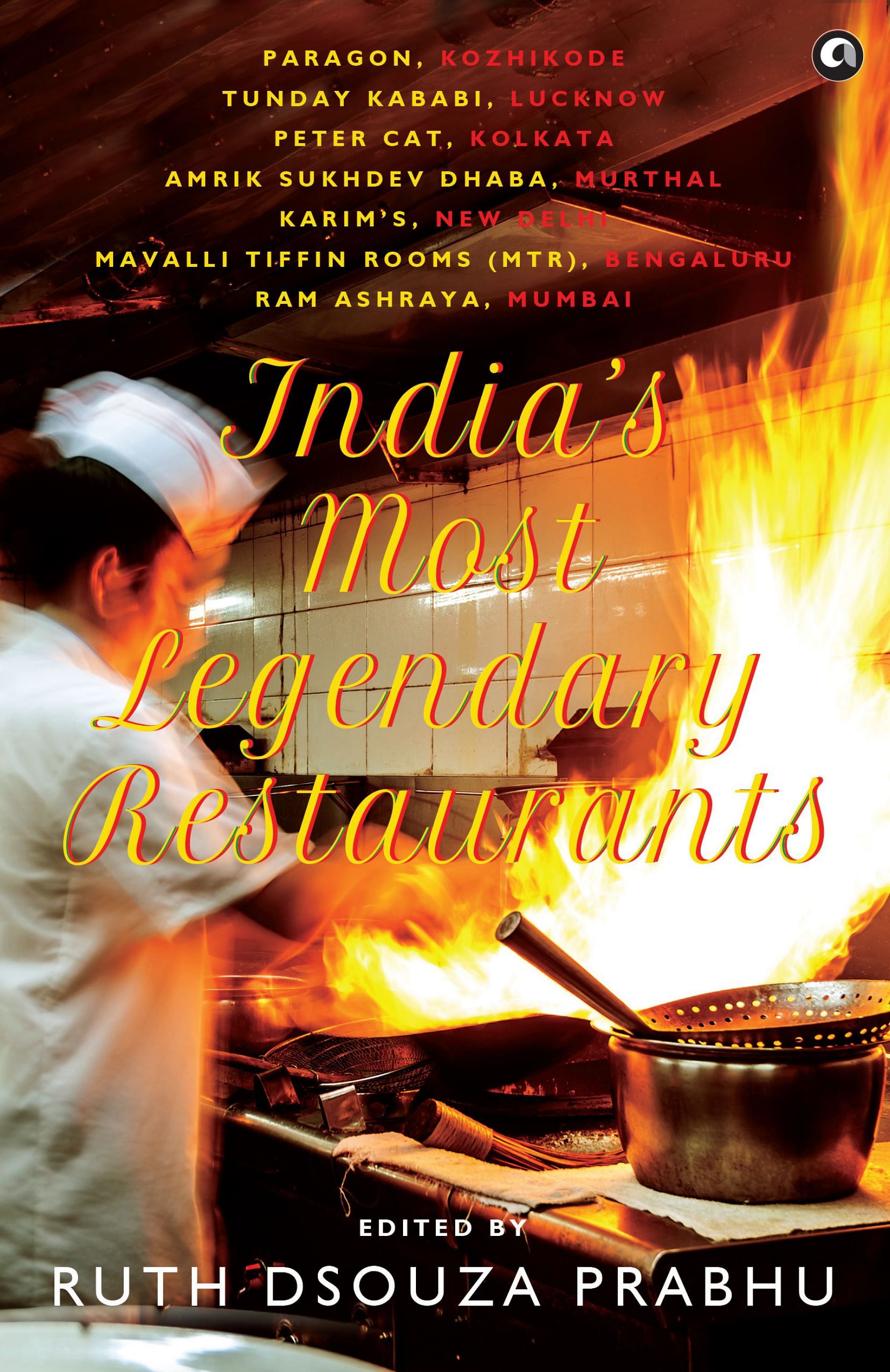

This excerpt from India’s Most Legendary Restaurants by Ruth Dsouza Prabhu has been published with permission from Aleph India.

This excerpt from India’s Most Legendary Restaurants by Ruth Dsouza Prabhu has been published with permission from Aleph India.