Modi’s battlefield, as a lone warrior with a larger waiting period for acceptability in India’s middle class than most of his contemporaries in their struggle for power, has never been confined to the electoral space. Once in power, the other constituency got equally important for him: the Great Indian Mindspace. He is not a proselytiser or an indoctrinator. He is a storyteller. Stories change nations.

He told them as motivational pieces, and the frisson was generated by the seamless blending of aspiration, dreams and patriotism, and the style varied from avuncular intimacy to prophetic grandeur to conversational casualness. And the India in his telling is not a fairyland—a familiar place in the fantasy of nationalist-autocrats—but a place rooted in hard realism. Its full realisation, he tells you, is the ultimate realisation of nationhood itself. Mann ki Baat, his storytelling session with India in which the listener becomes a part of the story, is the best episodic expression of a country that has ever emerged from a politician.

The great communicator may be a media construct that is too eager to turn every windbag on the stump into a Cicero, but certain politicians have had an easy access to the popular mind; for instance, storytellers such as Churchill, Reagan and Thatcher. They make political communication an art of alternative reality—beyond the wretchedness of the present lies a perfection worthy of us. As one of the most effective communicators in politics today, Modi makes the idea of the nation a shared enchantment among the millions who see in him their own unrealised possibility. That’s a sure recipe for a bestseller.

Still, even if the past propels his mission for the future, and even if tradition adds content to his modernisation agenda, the tomorrow he intends to build doesn’t draw its raw material from a perfumed history. The Modi of the marketplace makes the best use of technology to make India as egalitarian as possible. That is why the digital destiny is not just a trendy mantra but an acceptance of the inevitable. He is not a revolutionary in the

marketplace, and he has never intended to be a panegyrist of capital, and that is one reason for the disappointment of those who anticipated an Indian version of Reagan or Thatcher in him. As a gradualist reformer, he knew that India was in too unequal a place to withstand ruthless reforms.

Also read: Why Manmohan Singh’s India was similar to the failing Weimar Republic

The state still has a role to play, and the role need not be of socialist vintage, not a nanny state but a state that provides the best context to the individual’s most daring text. Modi gave his own nationalist spin to Deng Xiaoping’s famous aphorism: it’s glorious to be rich. The so-called start-up nation is a fine indicator of how the state doesn’t restrain the individual but frees him. The pinstriped Davos man can be spotted with a dash of the tricolour on his lapel. A true nationalist in the marketplace can afford only one ideology: freedom.

And it is this ideology of freedom that underpins his internationalism. India has come a long way from its leadership of ‘Third Worldism’—though as a mindset it may not have been fully eradicated from the establishment—and its relic, the Non-Aligned Movement, continues to get New Delhi’s patronage. Still, that is not the India that has got a seat at the global high table. In the India of the new Wise Man from the East, anti-Americanism is redundant, and national interest is not subordinated to a foreign policy built on borrowed ideology.

Modi’s India doesn’t belong to a bloc; it belongs to alliances and attitudes sustained by freedom, politically as well as economically. As a pragmatic globalist, Modi has achieved that rare feat of remaining a trusted friend to big-power antagonists, without devaluing his country’s international morality; Ukraine is a good example of this. With regard to China, India may have suffered from an inferiority complex for long, despite the advantages of democracy. It was as if an intimidated New Delhi made a diplomatic virtue out of its stoicism even as Beijing continued with its provocations along the border. Not anymore. Once again, this belated display of confidence in the dividends of freedom allows Modi’s India to strike a fine balance between national interest and international responsibility. Today, India’s global ambition matches its influence. No other prime minister after Nehru has excelled in the art of internationalism with such panache.

In the end, no politician in a democracy as unforgiving as India can play out a script of individual audacity and nationalist ambition without one quality: authenticity. Look around and you will realise that what those leaders desperate for postponing political mortality lack is the same quality. Authenticity comes from old-fashioned virtues a people disillusioned with the political class seek from a new leader on a mission: credibility, integrity and honesty.

Modi is not a ‘professional’ politician. He is a politician for whom politics is a permanent struggle of the most dutiful, and that too in one of the most deified nations. It is this devotion to the nation that adds a spiritual content to his idea of power. He has never been tentative about his relationship with power, which, in his book, is the most effective instrument for change, culturally as well as economically. He has turned power into the highest form of spiritual contentment, in which the personal blends with the national. It is this terrifying clarity of purpose that makes Modi authentic.

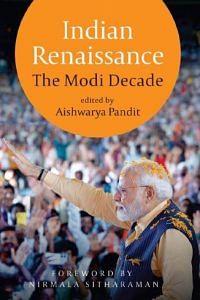

This excerpt from S. Prasannarajan’s essay in ‘The Redeemer’s Rite: How Narendra Modi Has Redefined Power’, edited by Aishwarya Pandit, has been published with permission from Westland Books.

This excerpt from S. Prasannarajan’s essay in ‘The Redeemer’s Rite: How Narendra Modi Has Redefined Power’, edited by Aishwarya Pandit, has been published with permission from Westland Books.