“After these elections, is it your intention to remain as president?”

Surrounded by squat, potted palm trees and brilliant marble slabs, Yahya took a long drag off his Chesterfield in the President House courtyard and contemplated the question. He put the cigarette down and exhaled, giving a little grin, as the folds of his neck jiggled over the too-tight collar of his starched white shirt.

“In our process of democracy, the people will elect their president. Unless I offer myself in the election, I cannot remain the president. And I am not offering myself in these elections.”

“You will not?” The off- camera Associated Press interviewer was skeptical that Yahya, or any leader in Pakistan for that matter, would ever relinquish power so freely.

“No. My temperament is not to be president. My makeup is not that way. I joined the army to be a professional solider, and my aim is to go back to my army. I have three years of service left, then I can retire. My only satisfaction is in restoring democracy to the nation— as a soldier. Does that answer your question?”

Indeed, it did. They wrapped the interview, both satisfied. Yahya was sharp today, sober, and it was time to put his foot down. Some of his generals suggested that he postpone the election or cancel it entirely. Nobody would be that surprised. There was always some excuse or another that they could use. National security, or the Indians maybe. But Yahya wouldn’t of hear it. He’d spent six months installing an unimpeachable electoral commission, and he’d funded it lavishly with one sole aim: to deliver a legitimate, fair, and free election. What use would it be to throw all that hard work away now?

Even Bhutto nagged Yahya about it. He suggested they stuff a few hundred ballot boxes— or at least close a few hundred polling places in East Pakistan to give them a little edge. Nobody would notice. Or better yet, he could just cancel the elections, then “kill 20,000 Bengalis and all will be well.”

Yahya scoffed. Gumming up the works now, so close to the finish line, would be like failing to build roofs on the buildings of Islamabad. It was preposterous.

Yahya would see this to the finish. He would deliver real democracy through real elections, not a fake democracy through fake elections.

Things weren’t always this tense between the pair. In fact, they drained a bottle of whiskey together almost every night. Tumbler in hand, Bhutto bitched to Yahya incessantly about the softness of former Pakistani leaders. Why couldn’t they be more like Stalin, a man who had just the right gut instincts? For Bhutto, the more grandiose the plan, the better. He thought that a thousand- year war with India would be Pakistan’s ideal policy.

Also Read: Pakistan lost the 1971 war, but its project of Islamist violence won the larger conflict

A few years earlier, Bhutto invited Yahya to share a meal at his Karachi mansion. Yahya stood in Bhutto’s opulent reading room, looking up at the shelves. His eye caught a beautifully embossed silver book displayed smack in the center. Puzzled, Yahya read the title: Mein Kampf.

“Aha! I see you are admiring my collection. That one is my absolute favorite, aside from the Mussolinis to the right, just over there,” Bhutto said. He thought that reading and rereading such works made him sophisticated, showed that he was learning from Europe’s great men.

Bhutto got his first taste for politics as a student at the University of California at Los Angeles and then the University of California at Berkeley in the early 1950s. He organized against Richard Nixon’s senatorial effort— the one where he earned the moniker “Tricky Dick” for slandering his opponent as a communist. When Bhutto returned home to Islamabad, his dad bought him a position as the country’s finance minister as a thirtieth birthday present. Bhutto loved the power that the position gave him, the control over other people’ lives. He married his first cousin, and when she couldn’t give him kids, he bought her a cottage a thousand miles away and then took a student as his second wife. As an Italian journalist described him, he was “born to charm [and] . . . he looked like a banker who wants to get you to open an account in his bank.”

Yahya knew in his heart that Bhutto was a true friend.

But now, just seven days before the election, Yahya couldn’t understand why Bhutto insisted on putting his thin banker’s thumb on the scale.

Bhutto made his case late into the night, trying to lean on Yahya’s army sensibilities: The conventional wisdom was that any Punjabi who would let a Bengali rule him would be a laughingstock; any leader who let it happen would be the ultimate disgrace to his clan and country.

But no matter how much he schemed, Bhutto never understood that Yahya’s mission from Ayub was to hold a free and fair election. Yahya refused to cheat, laboring under the same belief system that built Islamabad without a single kickback. He’d complete the mission to the letter.

Bhutto had a legitimate reason to worry. There were three hundred seats up for grabs in Pakistan’s National Assembly, a parliamentary body roughly similar to the US House of Representatives. The main difference from the American system (besides not having anything like a Senate) was that whatever party took a majority got to pick Pakistan’s next prime minister. If population were all that mattered, then the Bengali- speaking East Pakistan had an advantage with 162 seats against 138 in West Pakistan.

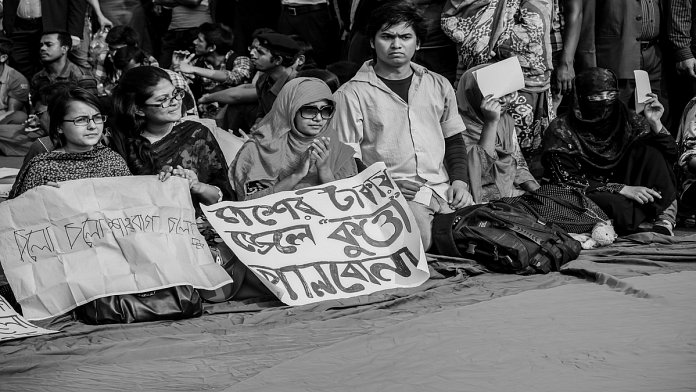

Also Read: Stop seeing Bangladesh as ‘East Pakistan’. Last 50 years are a missed opportunity

Although polling was nearly nonexistent, most pundits agreed that Mujib’s Awami League might secure about eighty seats at best, with the other eighty- two eastern seats split between Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party and an assortment of local parties. It would be a solid showing; Bhutto would be in charge, but Mujib would have enough power to influence policy.

Not to be stymied by Yahya’s unexpected backbone, Bhutto opened a new strategic front. He ordered his campaign manager to strike a deal with the opposition’s team. Three weeks before the election, at the InterContinental Hotel bar in Dacca, Mujib’s and Bhutto’s campaign managers hammered out a power- sharing agreement. Regardless of the exact number of seats either won, the deal ensured that Bhutto would be prime minister, and Mujib would get a bit more autonomy for Bengalis.

Bhutto loved dealing with Mujib. He was always so willing to believe in the words of men.

This excerpt from ‘The Vortex’ by Scott Carney and Jason Miklian, has been published with the permission of HarperCollins Publishers India.