‘Joining al-Qaeda?’ My father’s friend sounded more than alarmed when he called as I prepared to pack and leave for Doha to join Al Jazeera. The father’s friend was more like family and knew that I had been a kind of a problem child, prompting my parents to seek his counsel on more than one occasion in the past. Now, decades later, he feared he had more reasons to worry.

It was early 2003, and the drumbeats of war could be clearly heard across the world. The United States, fresh from what it felt was its resounding success in uprooting al-Qaeda by invading Afghanistan and toppling the ruling Taliban, was now in the final stages of invading Iraq to unseat its long-time ruler, Saddam Hussein. Separated by some 1,400 km from Iraq, I was set to fly into Doha at a time when the region was rapidly slipping into anarchic turmoil.

American troops were amassing in very large numbers in nearby countries – including in Doha, which was home to the US Central Command – when I arrived to take up my new job. Not many were convinced about my move. Al in Arabic is equivalent to ‘the’ in English, and to have Arabic names for shops and establishments beginning with Al is common. Qatar, with Doha as capital, is a peninsula, and in Arabic, Al Jazeera means ‘The Peninsula’. Few in India knew anything about the nuances, and they derived from the channel’s name whatever they wished to. That was the case with my father’s friend. Ditto with my mother. That Al Jazeera sounded somewhat similar to al-Qaeda was enough reason for her to be worried about my well-being.

Also Read: Journalists’ bodies condemn killing of Al Jazeera reporter in West Bank; seek probe

For its part, the international channel headquartered in the laidback but prosperous Qatari capital had raised hackles around the globe. It was an Arabic channel then and its aggressive reporting on the region, mostly ruled by despots and marked by lack of personal freedoms, was path-breaking. Countries in its neighbourhood resented it and would routinely ban it from being beamed within their respective borders. But the more the channel was hated, the more its popularity grew on the streets of the Arab world, and now it planned to launch its English arm – first a news website and then a full-fledged TV channel in English. I was among the first batch to arrive for its proposed foray into English.

Since the daring 9/11 attacks, Osama Bin Laden had been on the run, reportedly holed up in Afghanistan. The Americans demanded that the Taliban, ruling the country, hand him over to them. They refused, and the US invaded the country. But Bin Laden gave the American troops the slip and for some ten years – until he was eventually found and killed in the Pakistani garrison town of Abbottabad – no one seemed to know where he was hiding.

But Al Jazeera seemed to know. Every now and then, long before I arrived in Doha, Bin Laden would give exclusive interviews to Al Jazeera from his hideout. Either Al Jazeera reporters would go to meet him, or he would send his pre-recorded tapes. Whatever the case, Al Jazeera’s visibility – more appropriately its notoriety – skyrocketed with the airing of the Bin Laden interviews. People with little understanding of the local dynamics and how the region worked mistook the channel as an extension of the terrorist network of al-Qaeda. They were grossly wrong.

The real story is that Qatar is an extremely tiny country that has always felt threatened by its big neighbours like Saudi Arabia. Though rich – with massive reserves of oil and gas – it was never considered to be influential enough and was invariably bullied by its bigger neighbours. Ruled by an enterprising monarch – locally called the Emir – it saw an opportunity to increase its influence when Saudi Arabia backed out of a television channel that it had co-started with the BBC in the mid-1990s. The nascent channel’s reporting tested the limits of what the conservative Saudis could tolerate, and the partnership broke down. Suddenly, many Arabic journalists, suitably trained, were unemployed and available for employment.

The enterprising Qatari Emir who had unseated his father in a coup of sorts2 to come to power seized the opportunity, hired the jobless journalists and launched Al Jazeera. He was way ahead of his time in realizing that he who controlled information would ultimately command influence. Al Jazeera became successful, and as its owner – the channel is bankrolled by the Qatari government – Qatar’s importance grew manifold. It was no longer a pushover in a region dominated mostly by despots ruling large countries, and the Qatari Emir found a place at the high table at global meets to discuss regional developments.

None of the decision-makers, both in the West and also in West Asia, liked Al Jazeera. Yet, they couldn’t do away with it. The more Al Jazeera’s fame roiled the leaders – the then US president George Bush was widely reported to have discussed with British Prime Minister Tony Blair plans to bomb the channel’s headquarters3 – the more it grew in popularity. I often wondered why Bin Laden chose to give his interviews to Al Jazeera and no one else. I got the answer once I reported for duty. The logic was plain and simple: take, for example, Lalu Prasad Yadav, the once-powerful satrap of Bihar. His constituents were predominantly Hindi-speaking, and it made more sense for him to address them through Hindi TV channels such as Aaj Tak or Zee News. Giving interviews to BBC or CNN might have been more prestigious but of little consequence. The same logic possibly weighed in with Bin Laden. The supposed ‘jihad’ he waged was intended for Arabs, and Al Jazeera was the biggest Arabic channel with unparalleled reach. He, therefore, gave interviews to it.

Whatever the reason, Al Jazeera was controversial and was caught in the middle of escalating uncertainty over the invasion of Iraq. Its reporting reflected the mood on the ground, making it abundantly clear that few people in the region believed the Western spin that Saddam Hussein was being toppled because he possessed weapons of mass destruction. No such weapons were ever found.

Also Read: ‘You as Editor will be respected by politicians’ – Ajay Singh was told, he still quit media

The point of view that Al Jazeera offered had me hooked, though adjusting to the new workplace was hard. It was a different world altogether, far removed from my comfort zone in Bhubaneswar – my last posting before I left the country’s shores. It brought me down to earth by several notches. While in Odisha, I could walk in to meet the chief minister and also socialize with those considered influential. But in Doha, I quickly realized that my immediate past did not count. My new colleagues had not heard of Odisha. They knew about Kolkata, my place of birth, but only vaguely as the city that was home to the iconic Mother Teresa.

The ignorance, it turned out, cut both ways. I, too, seemed to know very little about what my new colleagues knew or were interested in. Just days after I joined, the newsroom went into a tizzy after news broke that a coup was under way in Guinea- Bissau. It was big breaking news, and everyone went to work while I sheepishly googled to find out where the country was. Around the same time, the channel devoted a lot of time and energy to cover a speech by Hasan Nasrallah about the Naqba. I knew nothing about both – the powerful chief of the Lebanon-based armed group Hezbollah or the anniversary marking the exodus of Palestinians from their homeland on Israel being born.

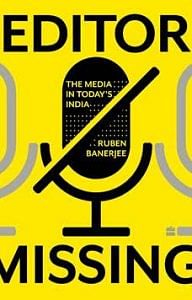

This excerpt from ‘Editor Today: The Media in Today’s India’ by Ruben Banerjee has been published with permission from HarperCollins Publications India.

This excerpt from ‘Editor Today: The Media in Today’s India’ by Ruben Banerjee has been published with permission from HarperCollins Publications India.