People who know them often say that cats can be ‘quirky, aggressive, and confusing’. A bit like them perhaps, this book can also be quirky and confusing at times, but it is, at least, completely non-aggressive. Non-aggressive, because no theories are being advanced here; none challenged. Clarifying further: referring to the idioms that commonly feature cats, one could say that nothing ‘comes out of the bag’ in this book; no ‘paw’ is ready to scratch; no one is being ‘set among the pigeons’. Nobody’s ‘tongue is being got’; no one hops on to ‘a hot tin roof’. And there certainly is nothing with ‘nine-tails’ in this book. This is simply a look—a bit quirky perhaps—at how the cat is viewed in India: how it was in the past, and how it is today.

It is not easy. For there are no connected accounts, and not a single book on cats written in the past is around. So, one gleans and glues: shards of things and accounts and stories, in the hope that a picture of how cats were viewed in our land emerges. A large number of references to them can be found in fables which India has been so rich in, and still remembers. There are, for instance, the Jataka Tales—stories of the former lives of the Buddha when he was a Bodhisattva, constantly in the process of evolving; and these go back to the centuries between the third and fourth BCE.

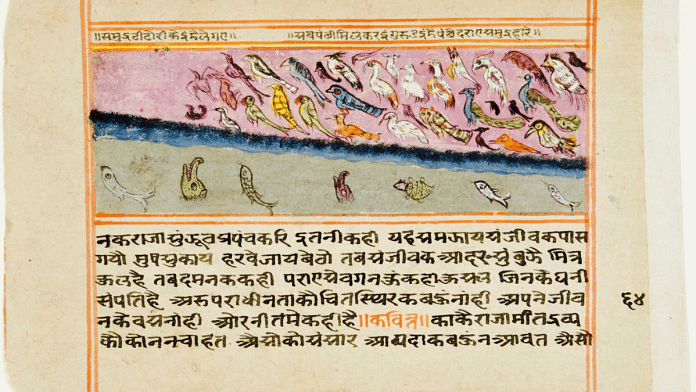

In these sometimes cats turn up as characters whose clever tricks or pretensions are—generally—foiled by the Bodhisattva who is always on the side of the wronged, the downtrodden. Not far from these tales is the core of the great classic which later came to be named the Panchatantra—‘Five Strands’, so to speak—a perennial favourite which has not only survived across centuries of time but which travelled all over the world and was translated, or transformed, in different languages at different periods of time. A version of this work, consisting as it does of ‘animal fables that are as old as we are able to imagine’, exists in practically every major language of India, but there also are close to two hundred known versions of the text in more than fifty languages of the world. Written somewhere

close to 200 BCE, it came to be known from ‘Java to Iceland’, as has been said; and drawn upon by Aesop at one end and La Fontaine at the other. Nothing is known with certainty about the author but a learned pandit, Vishnu Sharma by name, is generally credited with

having put the stories together to teach a king’s sons, through clever lessons in verse and prose, how to deal with situations in the real world. In Islamic lands also, the Panchatantra had a huge following, the three versions of it that became best known in India being the

eighth century Arabic version, Kalila wa Dimna, by Ibn al-Muqaffa, a fifteenth century version in Persian, the Anvar-i Suhaili, by the Sufi poet, Kashefi, and one translated by Abu’l Fazl entitled Ayar-i Danish, as commissioned by the emperor Akbar in 1588. Many of

these stories we shall go into later in this very work.

Several other compendiums of stories, most of them in Sanskrit, followed, borrowings being common and overlapping with minor variations not infrequent: thus, the Brihatkatha of Gunadhyaya; the Brihatkathamanjari of Kshemendra. The most comprehensive among these time-honoured works, however, was the tenth-century Kathasaritsagara by the Kashmiri scholar, Somadeva, written at the behest of King Ananta. Evidently, cats were never the subject proper of any of these works, but they surface every now and then, staring at you with those probing eyes, or sitting in quiet contemplation.

A delicious group of interconnected stories also came together in the highly entertaining Sanskrit work, the Shuka Saptati—‘Seventy Tales of the Parrot’—part philosophical, part erotic. The authorship of that widely popular work is still being argued among learned scholars, as also is its date, although on the latter there has emerged fair agreement that it comes from no earlier than the twelfth century. The net of the long story-within-story text is woven around a merchant who is about to proceed on a long journey and, concerned about how his wife might conduct herself in his absence, entrusts the task of keeping her on the straight path to a trained parrot who keeps telling her absorbing stories, one after another, night after night, just as she gets ready to go to her secret lover. The parrot succeeds but only after the enormous effort of inventing situation after situation in which men and animals and birds keep featuring, all in diverse contexts but all speaking the same tongue.

In this group figures, naturally, a cat. Not unexpectedly, the Sanskrit text attained great popularity in other lands and was translated in different languages, including Persian, the best-known version of it being by the Sufi poet Nakhshabi who rendered it in a very poetic

style in the Tuti Nama in the fourteenth century.

This excerpt from ‘The Indian Cat’ by BN Goswamy has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.

This excerpt from ‘The Indian Cat’ by BN Goswamy has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.