In the early decades of the twentieth century, those aligned with the Bengali bodybuilding society Anushilan Samiti, advocated the use of violence as a means for ending colonial rule in India. Within the north Calcutta Garpar Maniktala area, the Jugantar movement emerged under the leadership of Sri Aurobindo Ghosh among others.

It started under the guise of a fitness club but took young teenagers in and turned them into revolutionaries. Sri Aurobindo, who was ‘jailed by the British for plotting a sannyasi revolt against the empire’, combined his yogic spiritual impulse with nationalistic efforts. Violence emerged in Calcutta, with assassinations and underground groups creating chaos. The akharas and gymnasiums served as a means of physical strength building, as well as a cover for their political organizational efforts.

As the Bengalis’ organizational ability grew, the colonialist Lord Curzon and other British rulers countered the emergent threat to their hegemony with an attempt to partition Bengal in 1905. The Swadeshi movement, which was both a boycott of British goods and a promotion of indigenous goods, emerged in protest to the partition. It provoked and became springboard for Indian nationalism as a whole, and for subsequent Hindu and Muslim animation along communal lines. Swadeshi succeeded and Bengal was eventually reunited in 1911, but not without divisive societal ramifications becoming embedded into the communities. While the communal differences receded into the background, Indians in general hardened their demands.

‘In the wake of the Swadeshi movement’, the ‘anti-colonial revolutionary organizations’ flourished. The British responded by moving the colonial capital from Calcutta to New Delhi in 1912. The British crackdown on the insurgency within Calcutta was brutal. Freedom-fighters and revolutionaries were persecuted and served long jail sentences.

Also read: Not just by modern-day yoga fans, Patanjali was misunderstood even in history

Violence had less appeal in the 1920s and intellectuals fled during that time. Sri Aurobindo Ghosh, once an influential leader of Indian independence in Calcutta, left politics altogether to focus exclusively on spiritual practice. Still, fiery nationalism remained in Bengal. Subhas Chandra Bose, who served as Calcutta’s mayor and the leader of the National Congress, advocated violence when necessary. This conflicted with the idea of ahimsa (non-violence), a tenet within the Swadeshi movement, which Mahatma Gandhi carried forward.

Bishnu’s good friend and neighbour Nilmoni Das, a bodybuilder known as the ‘Ironman’, ran a competing neighbourhood gym and was said to have known ‘that many freedom fighters would practise body-building from his charts and he liked this idea. This is how he indirectly supported the freedom fighters.’ However, there was no indication that Bishnu Ghosh was active or involved in the independence effort, as supporting Indian nationalism wasn’t one of his father’s priorities. Many of his clientele were British colonialists such as Stanley Jackson, who was the governor of Bengal from 1927 to 1932, and his successor John Anderson, who served from 1932 to 1934.

Bishnu wrote:

Sir Hassan Surabardi was also very fond of me and once we were invited to hold a show in his house. Present were Sir Stanley Jackson, Governor of Bengal and his wife. They were completely fascinated by Buddha’s performance and in fact, Lady Jackson hugged and petted Buddha. Sir Hassan started his yoga lessons from Buddha right from that day.

On another occasion Bishnu wrote:

The Maharajah of Santosh had a tree planting ceremony and invited the Bengal Governor, Sir John Anderson. He had also arranged for me and my students to hold a show in his honor. My eldest son, late Srikrishna was just 3 years old then. The main attractions in the show were Buddha, Moni Roy and Srikrishna.

Also read: AYUSH ministry wants to make yoga asanas a sport, perhaps even an Olympic event

This should not to present Bishnu as the equivalent of a babu to the Englishman. Obnoxious colonialists were too common in his eyes; he saw himself as equal to any Englishman. In fact, Bishnu did not mind confrontations with the colonialists, even if it were sparked by something trivial, such as a bit of road rage: ‘We were finally in Calcutta, and on the way home I had a little tiff with an Englishman on the road – I won.’ Recalling another confrontation, Bishnu went on: We were an object of ridicule and hatred in the eyes of the English people those days; no wonder we too had developed a similar attitude towards them. They would not leave any chance of humiliating or insulting us. Once while travelling, I remember an Englishman put up his shoe-clad feet right towards my face. I picked up a pair of slippers and shoes with my big toes and put up my feet in front of his face. He put down his feet – so did I. He had met his match.

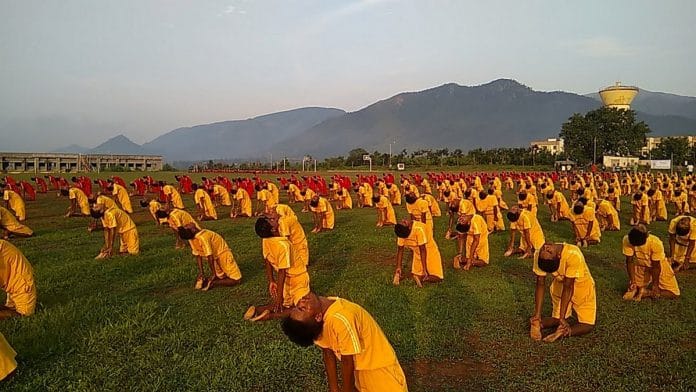

Bishnu loved to compete, and his approach to physical culture was one of professionalism rather than insurgency. It is an alternative ‘trajectory’ of physical culture, one not solely about nationalism but instead ‘a preoccupation with bodybuilding and feats of strength’, which ultimately led to the inclusion of Hatha yoga.

For Bishnu and his students, physical culture and feats of strength were a sport, and his students were professionals with rehearsed performances. Strongman feats were part of the lore of Bengal and India as a whole, but ‘a tension’ arose ‘in the physical culture movement’ between the amateur and the professional. With Bishnu, the emphasis upon physique and demonstrating muscle control on the stage moved to the forefront, a departure from the way Indian feats of strength and stage performances had been done in the past. An entirely new system was brought forth, which focused on the outward form, printed photographs and the integration of European methods (barbells and other equipment). Bishnu assimilated these with the yogic techniques of breath and contraction and relaxation techniques he had learned as a youth at the Dihika ashram. Soon, this would also impact the formation of a modern yoga system.

This excerpt from Calcutta Yoga: How Modern Yoga Travelled to the World from the Streets of Calcutta by Jerome Armstrong has been published with permission from Pan Macmillan India.

This excerpt from Calcutta Yoga: How Modern Yoga Travelled to the World from the Streets of Calcutta by Jerome Armstrong has been published with permission from Pan Macmillan India.