There are few debates on the merits of realpolitik versus ideology that would match the conversations in India about China. Not surprisingly, it can also become one of nationalism versus internationalism, however misplaced the latter may be in this case. This starts from our early years of independence, meanders through an era of conflict, witnesses the subsequent normalization, and finally arrives at the choice between a ‘Chindia’ outlook and an ‘India First’ one. The impact of the border events in 2020 have recently revived this argument, contributing to a growing awareness of the complexity of the challenge before India. As a result, facets like trade, investment, technology and even contacts have begun to be viewed from an integrated perspective. The current state of the relationship is clearly unnatural; what its future holds seems ripe for debate.

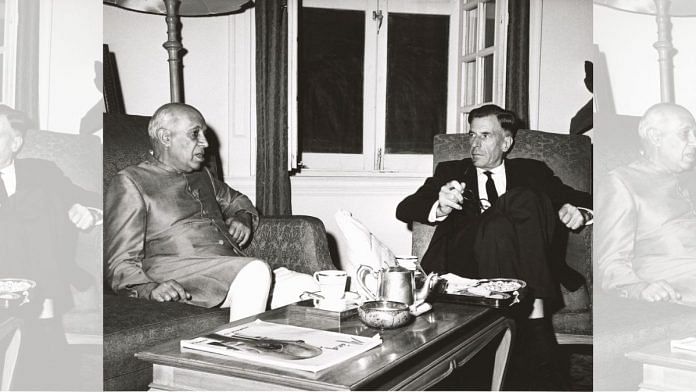

In essence, the competing perspectives derive from the differing viewpoints set out in 1950 by PM Jawaharlal Nehru and his deputy, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. The latter was as hard-nosed as they come and least susceptible to protestations from neighbours that diverged from ground reality. In his estimation, India had done everything to allay China’s apprehensions, but that country regarded us with suspicion and scepticism, perhaps mixed with a little hostility. Patel cautioned that for the first time after centuries, India’s defence had to concentrate on two fronts simultaneously. And his view of China was that it had definite ambitions and aims that shaped its thinking about India in a less-than-friendly way.

In contrast, Nehru felt that Patel was overly suspicious and stated in a note to him on 18 November 1950 that it was inconceivable that China would ‘undertake a wild adventure across the Himalayas’. Guided by a positive predisposition towards a leftist regime, he also felt that it is exceedingly unlikely that India may have to face any real military invasion from China in the foreseeable future. He appeared to take at face value the repeated references by China desiring friendship. To those who felt otherwise, he warned against losing our sense of perspective and giving way to unreasoning fears.

Each one eventually was to temper their view with some realization of the complications of a modus vivendi. The choice of words in what was an internal debate is obviously not quite diplomatic. But their gut instincts nevertheless were articulated quite clearly. One bet on a world of left-wing romanticism; the other voted for time-tested calculations about neighbours, especially big ones.

There were naturally multiple expressions of this divergence in approach, and that played out in the ensuing decades. As competition and even conflict characterized certain periods, public attitudes also started to take root accordingly. These may or may not have been shared by the governments of the day. Some displayed a consideration that was at variance with popular sentiment or even sought to shape opinion by advancing new objectives. Others were more hard-headed and would not let difficult issues be brushed under the carpet. Whatever the nuances, the defining imagery of diplomatic complacency remains the 1954 Panchsheel declaration.

If there is a common thread in the tendency to expect bestcase scenarios, it is the optimism of a particular brand of Indian internationalism. One illustration of this Nehruvian approach was in the debate about permanent membership of the UNSC. Whether it was feasible to successfully assert our claim at that point of time is an issue in itself, and would we have been granted the same consideration had roles been reversed is a corollary to it. But there was not even an attempt by India to leverage this issue for national gain, either with China bilaterally or with other major powers. It appeared that the basics of diplomacy had given way to the influence of ideology. Instead, Nehru’s decision in 1955 was to declare that India was not in a hurry to enter the Security Council at that time, even though it ought to be there. The first step, instead, was for China to take its rightful place. After that, the question of India could be considered separately. And no surprise, far from reciprocating Nehru’s ‘China First’ policy, we are still waiting for that country to express support for our own similar ambitions!

A very different situation reveals how deeply this mindset was divorced from ground realities. It was November 1962 and Sela and Bomdila had fallen to the advancing Chinese forces. As the then PM sought American help, he tellingly conveyed to the US President that because of its wider implications in the global context, India did not seek more comprehensive assistance. Apparently, we gave precedence to keeping distance from the West than to the defence of the nation! It is this lack of realism that has long dogged our approach to dealing with China. And it is precisely in this domain that we now see the difference.

If the positions and protestations of China got traction with an earlier generation, the state of Indian politics indicates that it is not altogether a vestige of the past. The previous driving factor was a desire to make common cause in the international arena. It was very much propelled by non-Western solidarity and Asian togetherness, more than tinged by ideological proclivity. Since then, public opinion has hardened and the earlier inclination to be excessively trusting is not maintainable. The world, too, is more transactional, and there have been decades of experience that influence thinking in India and China about each other.

Also read: When Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit was picked up by police for attempted assassination of Mussolini

How does the contemporary Nehruvian then approach the relationship? In times of stress as we currently are, like Nehru, the inclination is to indulge in ultra-nationalist rhetoric. This is done even while being in denial of the 1962 outcomes, when not actually misportraying it as something more recent. But ideology, habits and connections die hard. So, it is apparently necessary to have a double messaging, one for the more credulous within India and another for a different audience abroad. It is the latter that encourages them to advocate the view that China prizes harmony above all, without questioning why that does not apply to its neighbours. It also leads to admiration of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), while overlooking its violation of India’s sovereignty. There are less-than-subtle suggestions of China’s unstoppability by describing its rise as a force of nature and ill-concealed sympathy for its model of economic growth and technology appropriation.

This excerpt from S Jaishankar’s ‘Why Bharat Matters’ has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from S Jaishankar’s ‘Why Bharat Matters’ has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.