The main challenge was to understand the situation and figure out a solution. Dutee could either take hormone-suppressing drugs or have surgery to limit the amount of testosterone her body was producing. Or she could just give up and live with the stigma. But Dutee had begun to get angry about why she was being subjected to this form of humiliation. The athlete chose to fight the ban. ‘I wasn’t surprised,’ says Payoshni [Dr Payoshni Mitra, a PhD holder, researcher and activist in the area of gender and sports].

She called Jiji Thompson [director general of Sports Authority of India] and asked him to step in. In turn, Jiji asked Payoshni to act as a consultant to SAI on the case. ‘Of course, a few questions were asked about why I was bringing in an outsider for a case that was supposed to go nowhere. But I stood my ground,’ says Jiji.

Jiji was not a newcomer to the way bureaucracy works. ‘Bureaucracy is such a rusted engine that unless you push it yourself, nothing will ever happen,’ he says.

Payoshni got in touch with Dr Katrina Karkazis, an anthropologist and ethicist at Stanford University, who was advocating against the Hyperandrogenism Regulations. In turn, Karkazis emailed Bruce Kidd, a 1964 Olympics athlete, who had been speaking and writing against the IAAF’s and the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) hyperandrogenism policy for some time.

Also read: ‘Didn’t want to be burden on KIIT or Govt’ — Dutee Chand on why she wants to sell her BMW

Bruce, a former Canadian long-distance runner, then a professor and now the principal of the University of Toronto, Scarborough, has been an activist on gender equality and human rights for a long time. Since the regulations on hyperandrogenism were announced in 2011, Bruce has been involved with policy and is also part of most panels at the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES), the country’s national anti-doping agency.

In 2014, Bruce was the chair of the Commonwealth Advisory of Sport, the sport policy body advising Commonwealth governments. He was at a meeting in Glasgow in July 2014 when he got a mail from Karkazis, saying that an Indian athlete, Dutee Chand, had been suspended after failing the hyperandrogenism test. ‘Katrina asked me if I knew about it and I said no,’ says Bruce.

This is where the story of how Bruce got involved in Dutee’s case becomes incredible. The day after he received Karkazis’s email, Bruce was at a meeting of the Commonwealth nations’ sports ministers. He was sitting behind the Indian delegation, a group of SAI officers. ‘Honest to God, how often does that happen?’ asks Bruce. ‘The Indian sports minister wasn’t there but I raised the Dutee question with the SAI officers at the coffee break, then lunch, and by tea in the afternoon, I had made them understand that they ought to stand by their athlete.’

Bruce was told by SAI that if he initiated the test case, SAI would support it. Bruce got all the details he required from Payoshni and then wrote a long letter to Jiji Thomson. The question Bruce put to Jiji was: ‘Why doesn’t the Indian government challenge it?’ Jiji agreed.

Now the hunt began for a competent and well-known lawyer with some understanding of the case. All the Indian lawyers Jiji and Payoshni approached backed out once they were confronted with the contours of the case. It wasn’t entirely their fault. Hyperandrogenism sounded like a mystery virus.

Bruce got a call from Jiji. ‘He wanted a lawyer who wouldn’t charge an arm and a leg for fighting the case or would do it on a voluntary basis,’ says Bruce. He immediately called the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada and asked for a lawyer who had earlier been on cases for CAS. ‘There is a young lawyer in Toronto called Jim Bunting,’ was the answer.

Also read: I am a woman, I am fast: Dutee Chand, Caster Semenya and the battle against ‘sexist’ rules

Bruce had never heard of Bunting. He was on holiday at the time and the place he was staying had limited mobile connectivity. So Bruce hunted for a place where the signal strength was better and put through a cold call to Bunting. Bruce explained the case and Bunting immediately said, yes, adding that his firm would probably do it pro bono.

‘Dutee was an ideal test case,’ explains Bruce. ‘She is brave, no-nonsense, articulate and an attractive personality. I don’t know many countries where a woman would say: “Screw you. I am going to fight this.” That galvanised the world.’

By then in India, there was a new sports secretary, Ajit Sharan. He asked Jiji to brief him about the case that was making headlines. Jiji explained the situation and said Dutee would not take medicines or undergo surgery. The SAI, Jiji explained, was willing to fight the case in court. When Ajit asked how much this would cost and was told it would be about one crore rupees, or nearly USD 120,000, he tried to back out. But Jiji said SAI would try and cut costs in other areas. Jiji also met Sonowal and told him that questions needed to be raised in Parliament. So questions on Dutee were raised and the government was asked what it was doing to protect the dignity of a woman athlete. Well briefed by Jiji, Sonowal answered that the government would not leave any stone unturned to bring Dutee back on the track. He also said, ‘Hum Dutee ke saath hain (We are with Dutee).’

With the official mandate of the government, Jiji could work on the case without interference. But the AFI’s response was not encouraging. When Payoshni went to meet AFI chairman Lalit K. Bhanot and AFI president, Adille Sumariwalla, her request to support was not entertained. ‘We will not get any support from them,’ she told Jiji.

By the end of September 2014, the appeal was filed with CAS. Jiji’s arguments were simple. An athlete like Usain Bolt has the advantage of his stride. Swimmer Michael Phelps has several genetic advantages: a disproportionately vast wingspan, double-jointed ankles that give his kick an unusual range, and low lactic acid production which helps him recover from high-intensity exercise much faster than his competitors.

Did they ask Phelps to do something drastic about these advantages he was born with, or suggest medication which would have boosted his lactic levels, asked Jiji in the appeal. ‘Dutee was born with these flaws or advantages,’ says Jiji. ‘So why penalise her?’

The New York Times quoted Dutee on the subject of medically altering her body to fit the IAAF’s Hyperandrogenism Regulations: ‘It’s like in some societies, they used to cut off the hand of people caught stealing, I feel this is the same kind of primitive, unethical rule. It goes too far,’ she said.

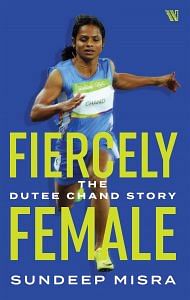

Excerpted with permission from Fiercely Female: The Dutee Chand Story by Sundeep Misra, published by Westland Sport, June 2021.

Excerpted with permission from Fiercely Female: The Dutee Chand Story by Sundeep Misra, published by Westland Sport, June 2021.