When Indian technology companies started setting up shop in Noida, the demand for such trainees grew. Companies were now also making optical instruments, photographic equipment, watches, clocks, calculators, computing machinery, transmitters and many similar things.

Unmarried girls were preferred for this work. They were young enough to not have an opinion of their own and were under the strict control of their fathers and brothers. There was less baggage to deal with.

Nisha’s father collected her salary every month. Initially, she resisted working at the factory. Long hours of sitting in dungeon like rooms, no leave even when you had a fever, and the watchful, lecherous looks of the supervisors were too much to deal with for the adolescent girl. The father had more trust in the supervisors than in Nisha’s reports of her experiences. After a couple of beatings from her parents for complaining, she surrendered.

When her father died in 1995, she became, at age twenty-four, the sole earning member of the family. Both her younger brothers, even though married by then, only worked sporadically: a construction site here, an office attendant’s job there.

Her salary paid the rent of the two-room house they lived in. The brothers occupied the two room with their wives. She and her mother, who had lost the privilege of having her own room after she was widowed, slept in the small courtyard at the back.

In the late 1990s, Bhagirath Palace in Chandni Chowk, near Red Fort, emerged as one of Asia’s largest electrical and electronics markets. It was a one-stop destination for a variety of electrical equipment and accessories, for both domestic and industrial use. Colourful decorative tube lights and bulbs, electric heaters, switchboards, wires and every other imaginable piece of equipment – the shops had it all and offered generous discounts.

The market also emerged as a hub for the import and export trade to Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Maldives and Bangladesh. It had more than 2,000 wholesale shops that started setting up their own small in-house electronic and electrical manufacturing units.

Kamal Kumar, the supervisor who had trained Nisha and many other girls to assemble radio transmitters, had moved to one of these wholesale shops. It made electric heaters, and electronic watches that could display the ambient temperature. Kamal was married with kids. He was twenty years older than Nisha.

He was the only one who would spend his own money on her, sometimes to buy a plate of chowmein, sometimes a cold drink or coffee. He was the only one who ever told her to ‘get some rest’. Over the years, their mutual affection and intimacy grew. There was no name for their relationship but a lot of comfort in it.

Nisha had heard that women are harassed and neglected in the paraya ghar, the house of someone else, that of their husbands, the marital home. But she felt she was facing that abuse and indifference in her own parents’ home.

She was not allowed to make friends. If her brothers found her eating chaat on the road or talking to a man at the bus stop, they would question her character. She was expected to bear with the insults to maintain harmony at home. Everyone was allowed to have an opinion on her actions, even her niece and nephews.

Also Read: How Dalits, Muslims, Adivasis encounter the State. ‘It has its boots on our necks’

Her brothers were more important to her mother than Nisha. She bitched about her sons to Nisha, but when it came to taking a position, it was always the boys that she sided with.

Poor guy didn’t take home-cooked lunch to work today! Poor thing has a headache but still went to buy veggies from the market! The mother had plenty of sympathy and praise for the sons. But not a word of approval or affection for Nisha – the one who was regularly earning and feeding them all. No acknowledgement. Nothing.

Nisha was now twenty-seven, but no one ever mentioned her marriage or made any efforts to arrange one for her. If not marriage, is there another way to get a new life, break out of this family, and see the world? she wondered. To her, a married woman seemed to have more rights.

An unmarried woman like her was always the apprentice in the house, secondary, never in the foreground. Unlike her, a married woman could wear make-up and colourful clothes, have a room of her own, get gifts as part of religious rituals, get rest, even get pampered when pregnant, and go to her parents’ home once in a while to relax.

Her younger brothers and cousins were married and were more respected at family gatherings than her. No one ever got up to offer her a chair or make her a cup of tea.

She was expected to hand over her entire salary to her mother. Many of her co-workers had a similar story: their families got used to their salaries and never attempted to get them married.

One day, she heard her mother talk about her distant aunt who was unmarried and lived all her life working in a government school as a sweeper. ‘She must have been cursed in her past life that she did not get married. She is frustrated and has no one to control her or

watch over her. Some people are born to die a lonely death.’

Her mother didn’t even notice that Nisha was sitting right there. Nisha had a perennial feeling of being isolated at home, uncared for.

The electronics industry had started employing so many women that even though under Section 66 of the Factories Act women were prohibited from working in factories between 7 p.m. and 6 a.m., in 1998, they lifted the ban for women in electronics.

Within a year of Kamal moving to Bhagirath Palace, Nisha also decided to move there.

When she told her family, her mother instantly blamed Kamal. Nisha was slapped, cursed, abused. They swore to cut all ties with her and locked her in the house for a week. But she knew she wanted to move not so much because of Kamal but to get away from her dysfunctional, selfish family that only wanted to squeeze her for everything she had but offered no warmth, no respite.

She did not realize her resolve to leave them had become so strong. One morning, she packed her bags and escaped, without a note, without saying anything to anyone.

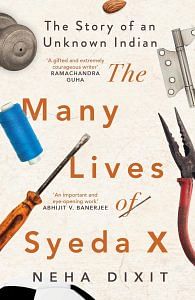

This excerpt from Neha Dixit’s ‘The Many Lives of Syeda X’, has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.

This excerpt from Neha Dixit’s ‘The Many Lives of Syeda X’, has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.

It is the unfair, low wage jobs that increase the employment. This is what needed to bring down unemployment. Minimum wage mandates increase unemployment. The former will decrease votes, the latter will increase votes for politicians.