Michael Creese in his book Jodhpur Lancers writes about one of India’s most charismatic cavalry regiments, raised and led by Maharaja Pratap Singh.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, European countries were keen to develop stronger commercial links with China, especially in the profitable opium trade. From time to time open war broke out, forcing the Chinese to grant concessions which included the establishment of trading posts along the coast – the British at Wei-Hai-Wei, the French at Kwangchowan and the Germans at Kiaochow. The traders were followed by missionaries, who wished to convert the Chinese to Christianity. The latter responded to what they quite reasonably saw as an invasion of their homeland, through a number of secret societies. Prominent amongst these were the Boxers, whose slogan was ‘Destroy the Foreigner!’

The Boxers were secretly supported by the Dowager Empress, Tzu Hsi. By the year 1900 the Boxers were out of control; Chinese Christians were massacred, missionaries tortured and killed, a railway station destroyed. In June, now supported by regular Chinese troops, they set fire to a large area of the capital, Peking. On 20 June, they surrounded the Legation Quarter of the city where the foreign embassies were concentrated. The countries whose legations were besieged responded by assembling the first truly multinational force in history, comprising troops from France, Germany, Great Britain, India, Japan, Russia and the United States of America.

The Indian contingent included State Forces from Alwar, Bikaner, Jodhpur and Malerkotla, and were accompanied by the Maharajas of Bikaner and Jodhpur. However, the siege was lifted in mid-August before many of the Indian troops arrived. It was not until 6 August that the 4th Indian Infantry Brigade, which included dismounted men of the Bikaner Camel Corps as well as the Jodhpur Lancers, was ordered to leave for China.

Amar Singh, a protégé of Sir Pratap, was a risaldar in the Jodhpur Lancers at that time and wrote a daily diary that gives us a first-hand account of the exploits of the regiment in China. He acted as regimental adjutant and secretary to Sir Pratap throughout the campaign. Sir Pratap was, of course, overjoyed at the news that the regiment had been selected for service overseas, with him as honorary commandant. Hari (Hurjee) Singh, a favourite of Sir Pratap’s, was the commanding officer.

Major Turner, a squadron commander in Gardner’s Horse and the senior British adviser to Imperial Service troops in Rajasthan, together with Captain E.M. Hewiss, also accompanied the regiment to China. When the orders to move were received the regiment was quartered at Mathura in United Provinces because of shortage of fodder in Jodhpur. They had relieved the 9th Lancers, who had been sent to South Africa to join other British troops who were fighting the Boers.

From Mathura the regiment went by special trains to Calcutta, where they embarked for China at the end of August, regimental headquarters being on board the SS Mohawk. After thirty days at sea, during which time the regiment lost six horses, the Lancers arrived at Shanghai on 24 September, and, having disembarked, waited there for a fortnight before they were assigned a task.

Sections of the regiment took part in the Nikko Shimanzai and Funnig expeditions, where they saw some fighting. At one time, the regiment was divided into fifteen detachments. Some of these were guarding the railway to Peking while others were sixty miles from it! On 8 October, Amar Singh and his squadron were ordered to take part in a reconnaissance sweep around Shanghai.

The squadron was divided into four patrols, Amar Singh accompanying one of them under the command of Jemadar Bhaboot Singh with twenty sowars that were to ride out as far as Wusung, about ten miles away. When the patrol reached the village of Wusung, Amar Singh sent back the following report: ‘Way is all clear. No signs of hostility appear at all.… Country all flat but full of canals and ditches.… Horses take to the stone bridges quite willingly. In some places the path lies alongside the line of houses’.

The patrol proceeded on to the railway station, from where Amar Singh sent a further report, before returning. (This report commented on the rain, which made the ground slippery, and also on the number of ditches and buildings that made the area difficult for cavalry.) Amar Singh’s reports were duly forwarded to the Brigade headquarters, and a staff officer – Captain Stewart – replied to Major Turner: ‘The General would be glad if you would express to Sir Pratap his appreciation of the way the Jodhpur Lancers worked today. He is afraid they must have had a very long and trying day for both men and horses. The country he knew was a very bad one but he had every confidence, which has not been misplaced, that the Jodhpur cavalry would get over it if anyone could.’

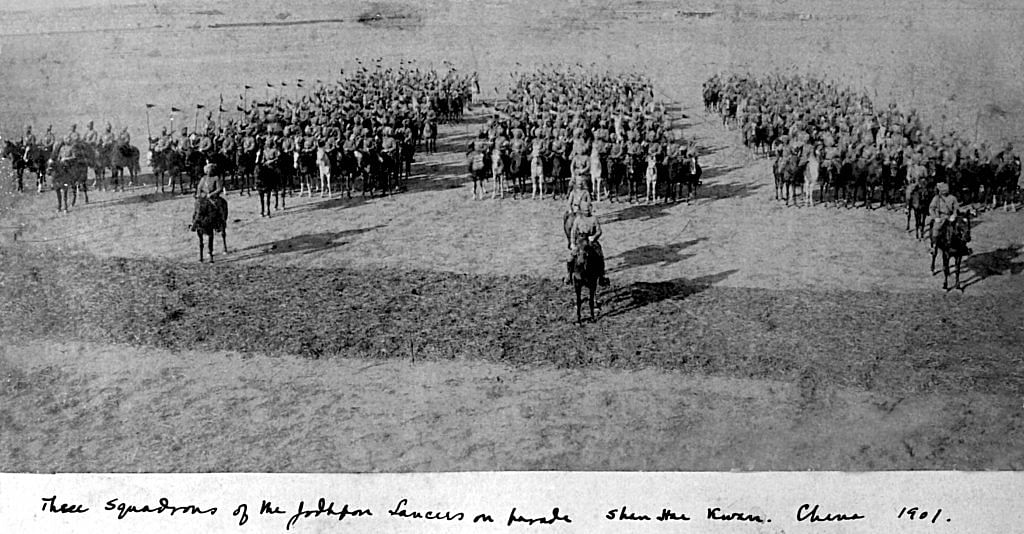

On 9 October, the Mohawk sailed to Shan Hai Kuan, northeast of Peking at the eastern end of the Great Wall of China and strategically sited on the coast road to Manchuria. Here the Lancers were to remain throughout the long cold winter. On the night of 31 January 1901 there was thirty-nine degrees of frost; the ink froze in the ink stands. Amar Singh commented in his diary that the city was dirty, filthy and very smelly but that the regiment’s quarters were good, with warm stables for the horses. The troops settled down to a routine of patrols searching for weapons in the surrounding villages.

On Christmas Day there was a gymkhana organized by the allied forces. The staff section of the Jodhpur Lancers won the tent-pegging competition and Amar Singh himself won a race which involved pistol-shooting and riding. Major Turner presented him with a silver bottle and two tumblers as a prize. Colonel Beatson wrote: ‘The officers and men had a full share of roughing it but they were always willing, ready for anything and absolutely uncomplaining. All showed great hardiness and withstood the privation and intense cold exceedingly well. The presence of Sir Pratap was a great incentive to all ranks by the splendid example he set, making nothing of the hardest work and privations in the severest weather.’

The regiment’s only serious engagement with the enemy came on 12 January 1901 when shots were fired at a Jodhpur party, which was out collecting wood by a large body of Chinese armed brigands, about five miles north-east of Shan Hai Kuan.

This excerpt and pictures from Jodhpur Lancers has been published with permission from Roli Books

This excerpt and pictures from Jodhpur Lancers has been published with permission from Roli Books