My tenure in the Fisheries Department ended in 1985 with my deputation to the central government as Chairman of the Cardamom Board. This lasted a full five years, my longest-ever tenure in any government posting. Full of enthusiasm and a youthful, knowall spirit, bolstered by my successes in certain aspects of my career, I blundered right away. The global market for small cardamom was dominated by purchasers in the Middle East and Saudi Arabia, who frequently drink a concoction called ‘kahwa’, prepared out of equal quantities of coffee and cardamom—this is not the same as the Kashmiri kahwa, which contains other spices, saffron, almonds, rose petals and honey. On the supply side, India dominated for years and years until it was found that cardamom can grow in parts of Latin America, too.

Guatemala entered the fray, and relying on the economies of scale and the productivity of virgin forest soil, severely undercut Indian producers and swept the market. The Arab buyers still preferred the taste of Indian cardamom, but when the price differential was too high, they turned to Guatemala.

Small cardamom was sold through auctions. The main growing area was Idukki district in Kerala, although some quantities were also grown in Coorg, Karnataka. Flushed with my previous successes in marketing agricultural commodities, I got the notion that I could control prices by laying minimum and maximum caps for the quantities offered in auctions. At the very first auction, prices went plunging down and never recovered thereafter. The growers were up in arms against the Cardamom Board and me, in particular. Large demonstrations were organized in front of my office. My relationship with growers of small cardamom was uneasy thereafter, right until the end of my tenure.

Also read: The woman who cooked her way into the story of India’s freedom movement

We retrieved the position for small cardamom later by marketing it heavily in Indian markets, promoting two health schemes. Boil water before drinking, we said, because microbes are destroyed in the process of boiling. To add a bit of flavour to the water, add a pod of small cardamom. The second theme was to chew a pod of cardamom when one felt the urge to smoke. These were not my ideas—they came from the experienced Secretary of the board, K.G. Nayar. The campaign yielded results and the vast Indian market began to open up for small cardamom. Over the years, long after I had left the board for greener pastures, an industry which had seemed on the verge of extinction had survived and was flourishing in the Indian market. This was not what I was required to do by the Commerce Ministry. Their focus was on exports, at a time when keeping domestic markets closed and starved was the leitmotif in Indian economic policy. New Delhi, with its many priorities and problems, hardly noticed this act of lèse-majesté.

A decision had been taken by the Government of India to bring other spices under the purview of the board and to convert it into a Spices Board. The procedures took quite some time, but ultimately an Act was passed in Parliament and we became the Spices Board. P. Shivshankar, a lawyer from Andhra, was the Commerce Minister then. The Government Joint Secretary at the time, D.P. Bagchi, told me that the minister wanted to appoint a politician as Chairman of the board and make me its Executive Director. The idea of working in a secondary position in an organization I had chaired did not appeal to me. I told him I would rather go back to my state government. Somehow, the minister’s idea did not materialize and I took over as Founder–Chairman of the Spices Board.

Before the Spices Board came into being, there used to be two organizations, the Cardamom Board—which I was heading—and the Spices Export Promotion Council, managed by an elected body of spice exporters. I had two immediate problems—to integrate the employees of the council into the new board, and to win over the spice exporters who were not comfortable with the bureaucratic takeover of an organization they had hitherto managed. The former task was accomplished with the help of the O&M (Organization and Methods) Wing of the Commerce Ministry, which was persuaded to create so many new posts that virtually everyone in both organizations got promotions—even some double promotions—in the new board. In the process, the staff union in the board vanished as their leaders became officers, while the officers of the council were treated with respect and understanding, and they merged seamlessly into the new board. The second task, I knew, would be a slow and laborious process.

In 1987, the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) hit the pepper exporters hard with an injunction of automatic detention of black pepper in US markets. This meant that our pepper would not enter the US markets without clearance from a laboratory approved by the FDA in the US. This meant more costs for the exporters and put them at a disadvantage vis-a-vis exporters from Brazil, Malaysia and Indonesia, who were India’s competitors. The main problem was the rodent droppings found in some consignments in excess of the limits prescribed by the FDA.

Solving this problem, therefore, became my priority. A delegation went to the US to meet their officials and importers. Led by the government’s Joint Secretary M.R. Sivaraman, it comprised several leading exporters and included me, as the Chairman of the board. Sivaraman had the reputation of being difficult, a tough taskmaster. When I met him for the first time in his chambers in Udyog Bhavan in Delhi, he cross-examined me very closely. Since I have always had the habit of going deep into all details relating to my job, I obviously met his expectations. We worked well thereafter, not only at that job but many others. In the civil services, it often happens that some officers loom large in one’s life and career due to more than one official relationship. Sivaraman was one such person in my career.

Some of the American importers were, frankly, rude. That was a time when India was treated as a poor and inconsequential third world country. When Sivaraman naively asked one group of importers if there were no rats in the US, one replied, ‘No rats here, except the ones to whom we have given green cards.’ Many Americans live under the delusion that being rude is the same as being outspoken. It takes time to understand their cultural mores. I came to realize later that they respect strength and deal more carefully with those who can benefit them commercially or politically.

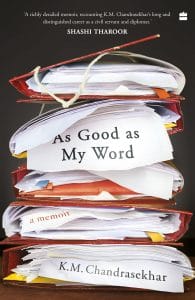

This excerpt from K.M. Chandrasekhar’s As Good as My Word has been published with permission from HarperCollins.

This excerpt from K.M. Chandrasekhar’s As Good as My Word has been published with permission from HarperCollins.