When he was on one of his visits to Jamshedpur, I told J.R.D. Tata that unless we found the money to modernize, both he and I would be standing at the gates of Tata Steel and selling tickets to see the Steel Museum, because that’s what we would become.

He laughed, but the message went home. Through his friends in Nissho Iwai, he arranged a visit to Japan for me. At that time, Japan was the pride of the steel industry, and I spent the month visiting all the newest Japanese plants-from blast furnaces to steel melting shops and rolling mills, from Hokkaido in the north to Kyushu in the south. A Japanese interpreter was attached to me for the entire month, so there were no communication problems.

Technologically, Japan held no surprises. What surprised me was the financial ability of the Japanese to knock down plants which were only ten years old, and find the money and the resources to build new plants on top of these ‘outdated’ ones. We, on the other hand, were continuing with our thirty-, forty- or even fifty-year-old units. Making improvements and improvising was our forte-producing new wine from old bottles’ was our favourite refrain-because all our plants were old, and we were trying to produce modern steel from those old units. People such as Dr Mukherjee, Dr Amit Chatterjee and others were at the forefront of turning out newer and newer steel from older and older plants. When I came back to India, I told J.R.D. Tata he should send his financial experts with me to Japan the next time! Once again, Mr Tata had a good laugh, but my message went home.

Of course, one of the reasons the Japanese could build those plants was that their banks were very supportive, and they encouraged debt-to-equity ratio of 8:1, even 10:1, in their steel companies, whereas in India we were stuck to a maximum ‘safe’ ratio of 2:1. We had a pricing problem too, as the Government of India controlled the prices entirely. These government-imposed financial restrictions meant we could not sell steel at the prices that were necessary and globally traded. Technically, we were competent; financially, we were handicapped.

Once we started moving into the 1980s, Mr Tata took the initiative to start some modernization programmes. India had started opening up, and we could get small amounts of foreign exchange sanctioned. I used to visit Delhi almost twice a week for financial discussions in those days. Luckily, we had aircraft which would take me from Jamshedpur to Delhi and bring me back the same day.

We started with a very small programme, which was to set up a bar and rod mill that would make long products. We had decided that making flat products would be more difficult than making long products, because of more stringent quality requirements. Long products, like bars and rods, could be made from steel that was not so high in quality. Thus the decision to start with a bar and rod mill.

After evaluation, we finally gave the project to a British company, Davys. That is a story in itself, because their competitors, Ashlow, were also in the bidding, and they lowered the price for the mill to very low levels in the hope of getting the order. But I knew that you must pay a price for the quality you want, and that belief proved to be correct, because after we gave the order to Davys, Ashlow went bankrupt and had to close down.

The project was relatively small, worth only Rs 80 crore, but in the early 1980s, it was a lot of money. We had fixed the date of commissioning for 3 March 1982, well in advance, to make sure that everyone was on the same page. Everyone, of course, cooperated, but there were problems, and the final issue arose when one day in January our engineers came to us and said that we really could not start the mill on 2 March.

I asked why, and they explained that there was a special oil for the gearbox of the new mill which was being transported from England. The ship it was on was stuck in Colombo, and there was no way to get the ship to Bombay on time. So out-of-the-box thinking was necessary. I asked them, ‘Do we have this sort of mill anywhere else?’ The answer was, yes. We had recently acquired a bar and rod mill at Tarapore, with the acquisition of a company called Special Steels. ‘All right,’ I said. ‘Shut that mill down, drain the gearbox oil there and transport it to Jamshedpur.’ People thought that I was a little mad, but in the end it was done. That oil was transported to Jamshedpur and put into our new gearbox, and the mill started exactly on time on 2 March. Once you are determined to do something, you can always find ways and means to do it.

Mr Tata and others came in and inaugurated the mill, and as far as I know, it is still in operation and running very well.

Modernization Story 2: New Blast Furnace

I will now move on to the case of a new blast furnace. Now, blast furnaces cost a lot. But we learnt one day that there was a blast furnace just sitting in its packaging somewhere in Portugal.

A Portuguese company with a majority government stake had ordered a blast furnace from the Italian company Italimpianti, but before they could set it up in Portugal, the European Union (EU) passed a diktat saying that if Portugal wanted to join the EU, no additional steel capacity could be set up, because Europe was overflowing with steel. To the Portuguese government, sacrificing a blast furnace was a small price to pay to join the EU.

When we came to know that this blast furnace was available in Lisbon, S.L. Srivastava, our chief engineer, and I visited the city. We saw the blast furnace and negotiated a very low price—$3 million-because the Portuguese were willing to throw it away. There were not many customers for a million-tonne blast furnace, particularly when the steel world was running well below capacity!

We shipped the furnace in three ships to Paradip. On entering port, we had to pay the usual customs duty. The customs officers thought that we had paid somewhere through other means and that this low price was not the actual price. They called me and interrogated me continuously for ten hours in Bhubaneshwar.

I had to answer all sorts of questions, write down my answers and sign each of them. I had no problem doing so, because I was describing exactly what had happened. I was telling the truth and had nothing to hide. Ultimately, customs released the furnace, and we brought the components to Jamshedpur.

J.R.D. Tata was in Jamshedpur at the time, and we did the bhumi puja for setting up the furnace in his presence. When JRD asked how long it would take to make it operational, I said we could do it in less than three years. He retorted, ‘Jamshed, you will never be able to do that. You have no experience in this, a new blast furnace. We have not built a blast furnace for forty years. How will you do it in three years?’ We took on the challenge.

Language was a major problem. The Italians had built the furnace, and the Portuguese were the customers. So, all the instructions and guidelines were in those two languages. But then we had good engineers. I particularly remember one— Amar Dhillon. Amar took charge of the stoves required to run the blast furnace. They were of a sophisticated nature, and we had not experienced such equipment before, but he took on the challenge. He and his engineers not only put up the stoves but also commissioned them.

We were able to stick to our promise and inaugurate the blast furnace in less than three years, beating the deadline by three days! When the time came for the inauguration (blowing in) of the blast furnace, Russi Mody, who was in Europe, was not available. So J.R.D. Tata himself came down from Bombay to Jamshedpur, and we inaugurated it ‘on time’. The two plaques are still exhibited on the G Blast Furnace-one carrying the date of the bhumi puja and the other carrying the date of the inauguration.

We did not have any contract with Italimpianti or the Portuguese after they sold us the furnace. To get a furnace of that magnitude, and that complexity, and work on schedule without any foreign advice—it was an example of not only our determination to stick to our timelines but also our willingness to give freedom to our engineers to do the things they had not done before. That furnace is still in service and has given us very good results.

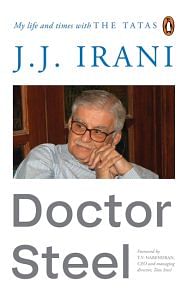

This excerpt from JJ Irani’s ‘Doctor Steel’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from JJ Irani’s ‘Doctor Steel’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.