A ROUSING PARTY WAS UNDERWAY at the Belvedere on the rooftop of Delhi’s Oberoi hotel. A balmy breeze had swept away the pollution haze; the city lights twinkled cheerily, reflected in champagne flutes and wine glasses as guests toasted the success of the HCL-Nokia partnership in India.

Away from all the hubbub and laughter, in a room adjoining the terrace, I—the host—was planning strategy. HCL and Nokia had shaped a revolution in mobile telephony in India, making the handheld phone affordable and accessible to the masses. It was a game-changer in telecommunications, with a cascading effect across sectors. It was Nokia which enabled our entrée into the telecom sector; the first of two significant pieces of business that led to a quantum leap in HCL’s size and revenues. Nokia had a long track record in mobile telephony, starting with mobile radio phones. In the 1990s, Nokia was providing GSM (Global System for Mobile communication) services across the world.

After Jorma Ollila became CEO in 1992, the company focused strongly on mobile telephones and telecom networks. The company entered India with the Nokia 2110 in 1994, and we partnered with it in the distribution of pagers and mobile phones, but the policy framework at the time was not conducive to the growth of mobile telephony, owing to high import tariffs on mobile phones and astronomical usage charges (Rs 16 per minute).

We had been in business with Nokia since 1995, and I had tried to persuade them to make their products more pocket-friendly in order to expand their consumer base, but failed. In any case, telecom represented a very small slice of our business in the 1990s. It was only when the regulatory environment changed in 2002, thanks partly to the efforts of the Indian Cellular Association, which we had cofounded, that I turned my attention to Nokia once again.

ICA’s Pankaj Mahendru and HCL’s J.V. Ramamurthy had lobbied relentlessly with the government and finally managed to bring the policy-makers around. The telecom sector was liberalized and licence fees for cellular service providers reduced, throwing the doors open to foreign investors. Service fees and call costs dropped sharply, enabling every middle-class Indian to afford a mobile phone. The market for handsets expanded exponentially.

I met with the Nokia team, determined to persuade them to change their pricing model. I argued with passion. Bringing the cost of a mobile phone down from Rs 16,000 to Rs 9,900, I said, would increase sales dramatically. I could guarantee the numbers. Three weeks later, Nokia got back to me and said it was on board. The success of the strategy was proven by the fact that we not only met the sales target, but exceeded it by a mile.

THE ODI STRATEGY

I called my sales heads and started what became known as the ODI model of sales (a reference to cricket’s ‘One Day International’ format). Every manager and sales person was given targets, not just quarterly, monthly or weekly, but daily. Our performance skyrocketed, proving my philosophy that the more you measure performance, the better it becomes. From a few thousand units a month, we were selling the same number every day.

Also contributing to sales was the fact that the phone wasn’t bundled with a service provider. So, the product and service were separate. We got the government to agree not to include the price of the phone in the AGR (Adjusted Gross Revenue). Nokia was suitably chuffed, and I deemed it appropriate to host a party for its people at our favourite hotel, the Oberoi.

After several mellowing rounds of drinks, I led them to a private room and launched into my pitch.

I said, ‘Ok, what’s next?’

Silence. Hesitantly, one of them said, ‘What do you propose?’

‘I think we need to rethink the price point. I would reduce it to Rs 6,999.’

This time, such was their faith in us that the Nokia people agreed without hesitation.

From then on, we never looked back. The eminently affordable Nokia 1100 handset, with a torch and an anti-slip grip, had been developed specifically for Indian conditions. Nokia had also acceded to our request for an ad campaign tailor-made for India. It featured a Nokia phone attached to the grill of a truck, to emphasize its dustresistance and durability. The torch was a great selling point, and demand was through the roof. In effect, we managed to sell a highend product in the smallest of towns.

In 2006, Nokia became the first mobile phone manufacturer to set up a facility in India. The idea emerged when I went to call on the IT minister, Dayanidhi Maran, and found him very receptive to boosting hardware in India. He was keen to bring electronics manufacturing to his home state, Tamil Nadu. This was music to my ears. HCL was equally keen for Nokia to start manufacturing in India. Maran moved quickly and cleared the way for Nokia to set up its unit in Tamil Nadu.

Nokia was an ideal partner, in that once it had made a commitment, it always delivered. Supportive, courteous and efficient, it never went back on its word. I learnt a lot about managing partnerships from the people at Nokia. Besides, for sheer hospitality, no one can beat the Finns, as we discovered when, as Nokia’s largest customer, we were invited to visit their headquarters.

From the moment we landed in Helsinki, we were accorded royal treatment. We were met off the plane, swept into a VIP lounge and plied with drinks, while someone dealt with immigration and our baggage. A limousine whisked us off to the Nokia headquarters at Espoo, near Helsinki, to meet chairman Jorma Ollila. He told us about the history of the company, founded as a paper mill in 1865.

It got into the electricity business in 1902 and moved into consumer electronics by 1967.

We delivered a presentation on Nokia in India and the chairperson declared himself delighted with our performance. At that point, Nokia’s market share of 70 per cent was its highest in any country.

Sustaining that momentum in the face of increasing competition was going to prove a tough challenge. In 2006, Ollila was replaced by Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo. When the latter visited India, we warned him that new telecom players were offering products like dual SIM phones with a long battery life, as well as good deals and services. To retain its dominant position, Nokia would have to support us in developing a competitive product, or do so itself. In the meantime, it could pick up a product from an ODM in Taiwan and use either the Nokia or HCL-Nokia brand. He turned us down flat. Perhaps the Not Invented Here (NIH) syndrome had kicked in. As we had predicted, Nokia lost market share. The handset division was sold to Microsoft in 2014.

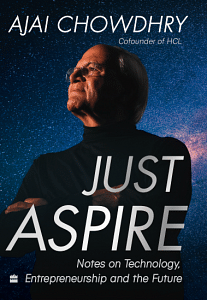

This excerpt from Just Aspire by Ajai Chowdhry has been published with permission from Harper Collins.

This excerpt from Just Aspire by Ajai Chowdhry has been published with permission from Harper Collins.