The early part of the 1990s was a troubled, hazy phase in Indian cricket. The bitter aftertaste of the events following the New York jaunt, as well as the events leading up to the Pakistan tour, lingered on, while the vexatious issue of player contracts continued to raise its foreboding head.

The BCCI quickly sized up the mood and decided it was time to stamp its authority to weed out any possible rebellion. In its collective wisdom, the BCCI used a subjective criterion as its weapon of choice—team selection—believing that was the best way to convey the message: toe the line and all will be well; challenge us and you will pay the ultimate penalty— getting the axe.

The avenues available to players of today were not even a distant dream then. There was no franchise cricket to offer them alternative employment. As it is, there was precious little money in domestic cricket (and several players were employed by public sector undertakings), which made adopting a contrarian (to the board) point of view a hazardous proposition.

Even the tenuous checks and balances (that the in-depth analysis and analytics provide these days) weren’t in place three decades back, so it became convenient for the authorities to use numbers, statistics and performances—or the lack thereof—as handy tools when it suited them. It was a clever, formidable plan: drop senior cricketers to quell any opposition and send out a strong message that if this could happen to the established players, no one was safe if they went against the grain.

Also read: Kapil Dev purposefully not invited for WC final to ensure he doesn’t hog limelight: Sanjay Raut

India were due to tour New Zealand early in 1990, which meant there wasn’t much time between their two overseas sojourns (between Pakistan and New Zealand). Action had to be swift and decisive, action that would extinguish any embers of fight left in the players. What could be more telling than the axing of the captain, Srikkanth, who doubled up as a statesman, and ensured that the Pakistan tour proceeded despite unpleasant and scary incidents? It made no difference that he had masterminded a 0–0 stalemate. He had to be made an example of, and his meagre returns came in handy—after all, Srikkanth had only managed to score 97 runs in seven completed innings.

The Indian board had already fine-tuned the art of high-profile sackings, doing it in pairs to convey that they weren’t singling one individual out. In the 1984–85 series, in the wake of the defeat to England at Delhi, the selectors wanted to send a strong message to Kapil, whose second-innings hoick (considered an irresponsible shot by the selectors) was deemed singularly responsible for the defeat. Kapil was axed for the next game at Kolkata, as was Sandeep Patil. But Kapil was immediately back in the scheme of things for the following Test in Chennai; Patil didn’t play for the country again

Collateral Damage

Shastri was the other casualty this time around. He had had at worst a middling tour—164 runs and 2 wickets—which was enough to justify the call to drop him. There was no doubting what the board was trying to tell the players: ‘We will play this game our way and by our rules, with the winner pre-decided by us.’

With Srikkanth out of contention, the quest began to identify the next skipper. He had to be a certainty in the side, but more importantly from the board’s perspective, he needed to fit the template they had outlined. He would have to be anything but flashy, a total conformist, someone who would follow instructions to the ‘T’. Who better than Azhar? The other ‘potentials’ were hardly established. And with the selectors sticking to the convention of nominating the most accomplished player as captain, it had to be Azhar. But though he was a natural in many respects, Azhar wasn’t the best when it came to communication, an attribute critical in a captain, a leader.

Following a mid-career slump, Azhar was just reinventing himself. What course would Indian cricket have taken had he not had the chat with Zaheer Abbas, and had Azhar not embraced his suggestion to score a hundred (which prolonged his Test career), is open to sustained debate. As it turned out, Zaheer Abbas influenced the cricket (and the cricketer) in his neighbouring country in more ways than he might have imagined.

Within a week of returning from Pakistan, the players plunged into Duleep Trophy. Srikkanth took a break to regroup from the rigours of the preceding tour, and the South Zone reins were entrusted to Azhar, who masterminded a semifinal victory over the formidable West in Bengaluru, and then steered the team during the title clash against Central in Hyderabad.

Also read: Bishan Singh Bedi challenged Mumbai’s dominance in cricket, took on BCCI for players’ rights

The zonal sides had been named when the Indian team was still in Pakistan. The West Zone selectors rested the players who were away on national duty, but the South selectors didn’t. Over a cup of tea and a smoke, Srikkanth said to W.V. Raman, ‘Rama, you might lead South, as Azhar and I are unlikely to play.’ Raman’s response was laidback, but also a clear and prescient statement, ‘You better play. If not, be prepared for a rude shock.’ A senior scribe who overheard the conversation mumbled about youngsters and the lack of respect for even the national captain, little knowing that the ‘disrespectful’ youngster was soon to be proved right.

The whimsical Raj Singh Dungarpur was the chairman of selectors, and at the Gymkhana Ground in Secunderabad, he approached Azhar with the famous words, ‘Miyan, kaptaan banoge [Will you like to be the captain]?’ The rest, pardon the cliché, is history.

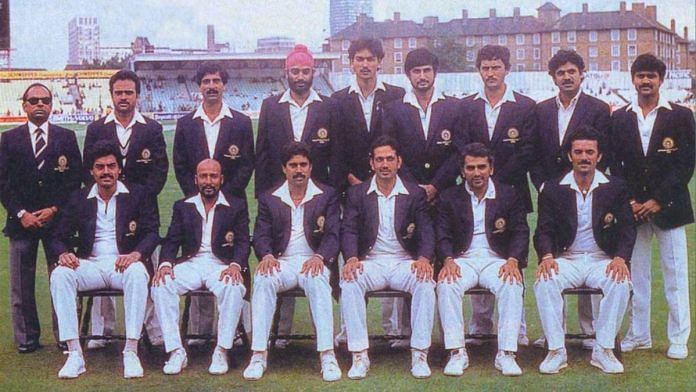

In keeping with their unstated intention to weed out ‘dissent’, the BCCI opted for a massive overhaul for the New Zealand tour. Armed with a flair for the dramatic, Dungarpur coined the catchy ‘Team of the ’90s’ phrase while announcing the squad. But how many from that squad survived even the first half of the 1990s? The actual team of the ’90s didn’t take shape until 1996, when Rahul Dravid, Sourav Ganguly and V.V.S. Laxman made their debuts, and linked up with Tendulkar, Kumble and Srinath, semi-veterans by then. But hey, who cared? Team of the ’90s, right?

This excerpt from WV Raman and R Kaushik’s ‘The Lords of Wankhede’ has been published with permission from Rupa publications.