Amol leaned back, his eyes scanning the café as if to ensure our privacy. Reaching into his pocket, he brought out a tissue paper. He passed along a folded piece of paper with it.

‘Don’t open it now, sir,’ he said, glancing around the café cautiously. ‘Read it back in your room.’

‘Hmm,’ I nodded.

‘I’m sure you will find enough in this,’ he said. ‘But please don’t keep this paper with you after you’re done reading. And unlike last time, only talk to a few people this time—you know how Chhattisgarh works.’

I nodded and hemmed again, put the paper in my pant pocket along with the tissue paper, and signalled the rock star barista of Bastar to bring us the bill.

‘Anything for me, sir?’ Amol grinned and asked after I’d settled the bill and we’d stepped out. Dusk was falling and the columns of mosquitoes rising from the open drain had thickened from the size of bamboo stilts to that of Greco–Roman columns.

‘How much do you want?’ I grinned back.

‘Arey, sir . . . chee chee,’ he bit his tongue and shook his head. ‘You know I don’t do such things.’

‘And you know I don’t have any information to give other than what you’ll read if I do a story, no?’

‘I have always cooperated with you because you’re an honest journalist, sir. But competition is tough these days. Promotions aren’t easy, you know.’

Amol, or for that matter any cop or rebel, never got any information from me. All I’ve ever offered is money to fixers and the promise of telling an honest, unbiased story to everyone else. So, it was a bit strange to hear Amol ask for information despite knowing that.

I left with a non-committal ‘OK. Let me think it over.’

Back in my hotel room, I locked the door, sat at the small table, opened my laptop and read the paper. The skies had been growling since I stepped out of the cafe and headed back to my hotel.

But now the wind had risen, and the growls had turned to deep, throaty roars. The mango, mimosa, jamun and coconut trees in the courtyard had just joined in the raucous choir of the storm winds when the first bolt of lightning struck somewhere close.

On cue, the bulbs went off.

Also read: AR Rahman to Nandan Nilekani—how ‘outliers’ view failure, uncertainty

The moment felt like a threshold. Ranu Tiwari still hadn’t called back. So, I didn’t know when or if I’d be able to enter the forest. But Amol’s paper was a real lead—one that would either bring me closer to the truth or push me deeper into the labyrinth of shadows and secrets that seemed to define Chhattisgarh.

Filled with tiny, handwritten notes, the paper was a chaotic yet meticulous collection of phone numbers, dates and amounts. Each detail was confined to hand-drawn boxes labelled with different sectors and towns—North Bastar, South Bastar, Raipur, Narayanpur, Bilaspur, etc.

I’d seen papers like this before. The numbers belonged to hawala agents who kept books for incoming and outgoing cash alongside some legitimate front business. They charged Rs 500 for every Rs 1 lakh they couriered. And they didn’t care who was sending or taking the cash as long as they got their commission.

Opening my laptop, I launched an Excel sheet and an Android emulator. I opened up Truecaller, an app that identified names associated with phone numbers, on the emulator, and started typing in the digits, noting the number and name in two adjacent columns in the Excel sheet.

I was looking for repetitions in names and payments of similar sizes made at more or less equivalent intervals of time.

After the third or fourth name, I called room service and asked for a refill of Nescafé sachets.

‘Thoda zyada dijiye, please [Give me some extra please],’ I requested the young tribal girl who had picked up the phone.

The attentive young woman, drenched by the first flush of spring thunder-laced rain, handed me not only coffee but also a thermos flask of hot water, two candles and a matchbox.

‘Sir . . . dinner thoda jaldi bol dijiyega aaj [Please order dinner a little early tonight],’ she requested.

‘Sure,’ I said. But I wasn’t sure how long this night would be.

Like most uninitiated people swayed by movie avatars of investigative journalists, I too had once thought that being one would mean using hidden cameras, doing sting operations, travelling undercover and similar exciting things. I was misled into believing I’d wield a camera or a recorder like secret agents wielded weapons.

The truth I had learned over the past years of work was that the laptop, an Internet connection and spreadsheets would be the most useful weapons in my arsenal.

‘If you can’t do basic accounting and use Excel,’ Ben Lesser, a senior data and investigative reporter with Reuters and the professor who taught me the eponymous class at Columbia, had told me, ‘you can kiss investigative journalism goodbye.’ And within that ‘follow the money’ was the drill, no matter how unsexy and boring it apparently was.

Also read: Sufi saints and Sultans in Delhi—a delicate balance of asceticism and politics

Soon, I forgot all about dinner, coffee and cigarettes. The hotel, power cut and storm, all blurred out, I typed and jotted, jotted and typed.

The numbers were not only throwing up names of people but also those of companies. There were construction material suppliers, contractor companies and a lot of names that only said ‘XYZ Enterprises’.

I copied and pasted the names into Google Maps and tried to match them with the sectors and town blocks they’d been put in. Most locations matched what Amol had written. The intel was good.

As the jottings and mappings increased, some strands thinned, others thickened, and the web began revealing itself. In front of me stood the real enormity of the so-called Maoist–State conflict of Chhattisgarh.

This wasn’t just a black-and-white conflict between two competing powers. It was an industry. An industry where an innumerable many, small and big, on this side and that, made money off this tango the Maoists and the State had been dancing for fifty years.

The biggest hurdle to ending the conflict was neither the distance of the revolution nor the brutality of statecraft. It was the innumerable middlemen who didn’t want a curtain call on the tango because they made their millions off it.

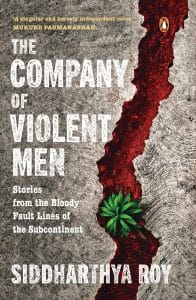

This excerpt from Siddharthya Roy’s book ‘The Company of Violent Men’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Siddharthya Roy’s book ‘The Company of Violent Men’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.