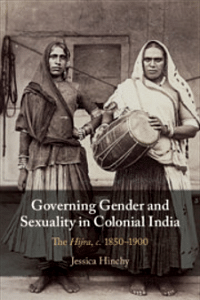

On the 17th of August 1852, a Hijra named Bhoorah was found dead with her ‘head nearly severed’ in the north Indian district of Mainpuri. In the aftermath of Bhoorah’s violent death, the British rulers of north India resolved that the Hijra community should be rendered extinct. Hijras like Bhoorah performed and asked for badhai (a ‘congratulatory gift’) following the births of children, at marriages and in public spaces.

They embodied a feminine gender identity, for instance through women’s clothing, and described themselves to colonial officials as having been either castrated or ‘born that way’. Hijras were initiated into discipleship lineages that linked generations of gurus (teachers) and chelas (disciples). Bhoorah had attained guru status and had two disciples, Dullah and Mathee, with whom she lived. For two years, Bhoorah had also lived with her male lover, Ali Buksh, but shortly before she was murdered, Bhoorah had left him for another man. On the 17th of August, Ali Buksh forced Bhoorah to return to him. Neighbours saw the couple arguing in the street before entering their house. Later, Bhoorah’s disciple Dullah ran out into the street, shouting that Ali Buksh had murdered Bhoorah. In the subsequent murder trial, there were two suspects, Ali Buksh and Dullah, but the British judges were convinced that Ali Buksh had killed Bhoorah due to the ‘severance’ of their ‘infamous connexion’.

Although a Hijra was the victim of the crime under trial, the judges criminalised Hijras as cross-dressers, ‘beggars’ and ‘unnatural prostitutes’. One judge called Hijras an ‘opprobrium’ upon colonial rule, while another claimed that the continued existence of the Hijra community was a ‘reproach’ to the British government. Bhoorah’s death sparked an anxious discussion in the official circles of the province in which she lived, the North-Western Provinces (NWP). British administrators claimed that Hijras – or ‘eunuchs’ in colonial parlance – were ‘habitual sodomites’, beggars, an obscene presence in public space and the kidnappers and castrators of children. In 1865, the NWP declared that its aim was to ‘reduce’ the number of ‘eunuchs’ and thus ‘gradually lead to their extinction’. The province launched an anti-‘eunuch’ campaign that had the explicit goal of ‘extirpating’ or ‘exterminating’ the Hijra community.

This project of elimination was formalised under the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA) of 1871. While the much-studied Part I of the CTA targeted the ‘criminal tribes’ – groups that were apparently hereditary criminals by caste occupation – the under-examined second part of the law targeted so-called ‘eunuchs’. Under the CTA, Hijras would find their gender embodiment, domestic arrangements and livelihoods scrutinised and policed in new ways. The anti-Hijra campaign was a provincial project, since Part II of the CTA was enforced specifically in the NWP. The CTA required police to draw up registers of the personal details of ‘eunuchs’. Specifically, police had to register ‘eunuchs’ who were ‘reasonably suspected’ of sodomy, kidnapping and castration, thus legally defining a eunuch as a criminal and sexually deviant person. The 1871 law provided police with increased surveillance powers; prohibited registered people from wearing female clothing and ‘adornments’ or performing in public; provided for the removal of children in registered people’s households; and included provisions that interfered with Hijra discipleship and succession patterns.

The short-term aims of the law included the cultural elimination of Hijras through the erasure of their public presence. The explicit long-term ambition was ‘limiting and thus finally extinguishing the number of Eunuchs’.

Fortunately, the Hijra community survived these colonial attempts to cause their ‘extinction’ and is evident today in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Given the present-day social marginalisation and police abuse of Hijras, the history of Hijras’ interactions with the state is a pressing issue.

Also Read: Being transgender is not a choice: Manipur actor recalls journey to recognition

For many colonial officials, Hijras were not only a danger to ‘public morals’, but also a threat to colonial political authority. The colonial government thus viewed the policing of Hijras as an ‘important branch’ of the ‘duties’ of ‘district officers’ and a priority in local policing. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Part II of the CTA received a greater level of attention at the upper echelons of government than did section 377 of the 1860 Indian Penal Code (IPC), which prohibited forms of non-reproductive sex defined as ‘unnatural’ intercourse until 2018. To many high-ranking colonial officials, the small Hijra community endangered the imperial enterprise and colonial authority. If we are to understand colonial sexual regimes in India – indeed, colonial governance in general – it is important to explore why this was so. The colonial Hijra archive also gives unusually detailed insights into the impacts of colonial law on colonised peoples who were marginalised because of their gender expression, sexual practices and intimate lives.

To some historians who have stumbled across the sizeable volume of documents about ‘eunuchs’ in colonial archives, this project has appeared a ‘strange’ preoccupation, to quote Christopher Bayly. Rather than dismiss the ‘eunuch problem’ as an odd colonial concern, this book takes seriously, and seeks to explain, the intense official concern with Hijras. Yet the colonial policing of Hijras has been almost entirely absent from the historiography of late nineteenth-century India, despite a growing body of scholarship on gender and colonialism. This is the first book length history of the Hijra community.

This excerpt from ‘Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India: The Hijra c. 1850-1900’ by Jessica Hinchy has been published with permission from Cambridge University Press.