Although the Sylhet referendum is an invisible footnote in Indian history, its impact has been manifold, the most significant being that the Bengali Hindu population from Sylhet relocated to Assam. The plan to keep Sylhet out was aborted. The Assamese-Bengali faultlines would only grow worse from this point onwards. In a couple of decades, multiple violent assertions based on identity emerged, jostling against each other for hegemony.

On the other hand, an apolitical Hindu Sylheti identity was already a threat to many communities and tribes as Bengali settlers started spreading across the region. The Bengali-Assamese relationship was strained because historically, once Sylhet came to Assam, the Assamese saw Bengalis, who began dominating the region, as usurpers of land and jobs. Even though Assamese leaders were relieved that Sylhet went to Pakistan, the Partition did not help; the Bengalis had already created their own pockets of influence and swiftly moved in and settled inside Assam, deepening the antagonism between the two communities. Language became the trigger and the Assamese started the bhasha andolan demanding their right to their language. This was one of the first instances of identity mobilisation based on language and it took place on both sides of the border—in Assam, the Assamese language over Bengali, and in East Pakistan, it was the clash of Bengali over Urdu that eventually formed a new nation, Bangladesh.

While historians usually see the Partition as a line that cut through Bengal and Punjab, they often forget that it went right through Assam and Tripura as well. Bengal was partitioned 201 times that included 197 enclaves. Unlike West Pakistan, in the East the Long Partition started in 1947 and continued till 1971.

Also read: Stop seeing Bangladesh as ‘East Pakistan’. Last 50 years are a missed opportunity

While a new homeland was created for the Bengali Muslims which eventually became a country with no territorial loss, the Bengali Hindu was destined to be a refugee. Unlike Punjab, the Partition in Bengal was a long-drawn and unending process. People had to change their citizenship multiple times. In many cases, they were not (and are still not) sure of their citizenship. Nor are they certain of their identity—refugee or migrant or outsider.

While a new national identity based on religion was taking shape in Pakistan, East Pakistan was still stuck in limbo. The majority of the population of this new country lived in East Pakistan, but was being governed from a distance of 1,500 kilometres. Pakistan’s stateformation challenges were far greater compared to those of India. The biggest challenge at the time of the country’s birth was its obduracy in imposing Urdu as a national language. The Bengali language became a rallying point, although this linguistic identity was not strong enough to avert the genocide of 1950. The irony, however, is lost to history: a Hindu Bengali, Dhirendranath Datta of the Pakistan Congress, was among the first to raise the demand for Bengali as national language in the Pakistan Constituent Assembly. Datta and his son were allegedly tortured and killed by Pakistani authorities in 1971 on charges of seeking to disintegrate the country. Their bodies were never found. Interestingly, in independent Bangladesh Datta’s family property was confiscated, and he was never duly acknowledged.

Bangladesh’s relationship with the ‘Bengali’ has been paradoxical, moving between a kind of longing and hatred, a tension that has forged an absent Bengali identity which moves between victimhood and anxiety. The East Bengali or the Bangal’s (almost a pejorative in West Bengal, referring to the Bengalis of East Bengal/Pakistan/ Bangladesh and to refugees in Assam, the Hindu Bengalis are called Bongals and the slur for a Muslim Bengali is Miyah) relationship with Bangladesh has been paradoxical, moving between a kind of longing and hatred, a tension that has forged an absent Hindu Bangal identity that moves between victimhood and anxiety. The Bangal in absentia has detached her/himself from the process of history to cling to some moments in the past.

In the four days of 16–19 August 1946, unprecedented communal killings in Calcutta were reported. Some 5,000-10,000 people died,

around 15,000 were injured and there is no authentic casualty figure to this day. Witness testimonies in this massacre were considered partisan and therefore lack clarity. Private, public and official memory all remain buried in the Great Calcutta Killings.

The killings and hostility seemed to have vanished with Independence, but tensions between the Hindus and Muslims continued to simmer after the Partition. From 1947 through 1950, sporadic incidents were reported, but large-scale rioting was avoided.

News of Muslims killed in Howrah in West Bengal incited passions in East Bengal. On 10 February 1950, Dhaka observed a ‘protest’ day.

Also read: Bengal Partition stories aren’t like Punjab. You won’t find violence, but a world was lost

Self-styled leaders made speeches at Paltan Maidan, calling upon Muslims to avenge the Calcutta killings. Hindus across East Bengal were attacked with blood-for-blood slogans. Ownership of shops

changed hands swiftly. It was now that the Muslim middle class also engaged in violence. Barisal was the worst affected. All Hindus under Muladi thana were killed. Hindus in Bhairab Bazar in Mymensing

district were also wiped out. The Hindu families who survived were forced to leave now. The exodus began. Bengal and Assam witnessed a surge in refugees. During the period 10 February–16 April 1950,

some 14,00,000 refugees fled East Pakistan. At the same time, around 400,000 Muslims left India.21 The movement of refugees continued for months. Home Minister Sardar Patel suggested that Pakistan provide land to resettle the refugees. On 8 April 1950, the two prime ministers of India and Pakistan, Nehru and Liaquat Ali, signed the Nehru-Liaquat Pact defining the position of minorities in both countries.

Under this agreement, minorities of both countries would enjoy every right granted to a citizen. It also ensured that migrants could move freely from East and West Bengal, Assam and Tripura with as many household goods as they wished to carry with them. Migrants could also return to their homes if they chose. If they returned by 31 December 1950, ownership rights would not change and they would be able to dispose of their property, exchange land, or otherwise claim their land. The provision included every single person who had left since August 1947. The Pact had other provisions for inquiry committees, the search for abducted women, etc., none of which was implemented on the ground. Almost all prominent Hindu families and professionals were forced to leave East Pakistan.

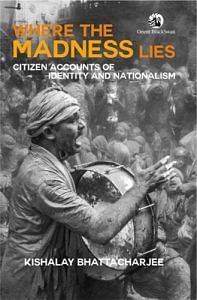

This excerpt has been taken from Kishalay Bhattacharjee’s ‘Where The Madness Lies: Citizen Accounts Identity and Nationalism’ with permission from Orient BlackSwan.

This excerpt has been taken from Kishalay Bhattacharjee’s ‘Where The Madness Lies: Citizen Accounts Identity and Nationalism’ with permission from Orient BlackSwan.