It is often said that Bengal Partition in comparison with that on the western border of India has not received much literary attention. Some even go to the extent of saying that celebrated Bengali writers more or less remained ‘silent’ regarding this cataclysmic issue. Thus, ‘Partition Literature’ has become almost synonymous with the writings of Saadat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, Bhisham Sahni, Ismat Chughtai, Intizar Hussain, Joginder Paul and others, and we often tend to ignore the contribution of the authors from the eastern and north-eastern parts of the country and Bangladesh.

This obviously speaks of a politics in the formation of canon particularly when it is evident that Bengal Partition fiction is no less powerful and appealing than its western counterpart. One may think of short stories and novels by the authors like Jyotirmoyee Devi, Pratibha Basu, Ramesh Chandra Sen, Satinath Bhaduri, Manik Bandyopadhyay, Narendranath Mitra, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Atin Bandyopadhyay, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, Prafulla Roy, Debesh Ray, Sadhan Chattopadhyay, Amar Mitra, among others, from this side of Bengal, and Syed Waliuallah, Hasan Azizul Huq, Rizia Rahman, Selina Hossain, Akhteruzzaman Elias from that side, which is Bangladesh. The list of authors of Bengal Partition literature is not only huge in its corpus but immensely relevant in the socio-political context of the present day.

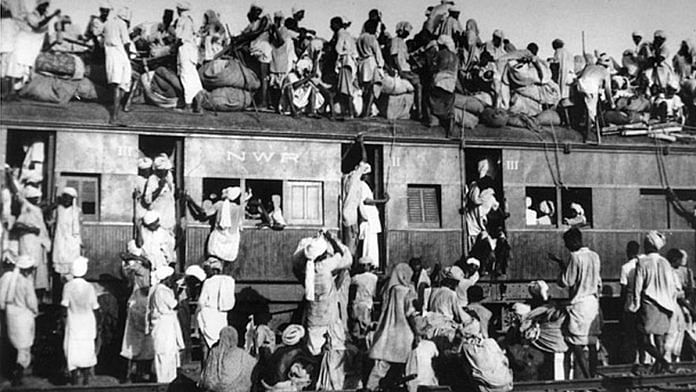

The stories of the present anthology include some of the most striking and dominant themes of the Bengal Partition and its aftermath. One major theme is obviously the ceaseless movement of rootless masses in search of safe shelter in an ambience of generalised violence. Dinesh Chandra Ray’s ‘The Guardian Deity’ depicts the journey of refugees (on the road, through the forests and even crossing the river) in the direction of Hindustan when communal riots began. The protagonist of the story thus narrates her own experience: ‘There was a journey of three days and three nights ahead of me… There were robbers at the street-corners hiding in darkness. Yet I was taking myself forward safely; there was some sort of a valour in it.’ The experience of the narrator is therefore represented in a positive light because once she is on her way, she is free from her past which was almost synonymous to the strict rules imposed on her by her father-in-law in the name of the service of the deity. But this kind of depiction of a journey is very rare in partition stories. Border-crossing is almost always portrayed as a terribly painful and wearisome experience in these narratives. One may remember the agonised experience of Rajab Ali, the central character of Devi Prasad Sinha’s ‘Border’: ‘…that is the border. So impossibly long, impenetrable has become this little path—as if someone is pulling a piece of rubber continuously from both the ends—no matter how much he runs, the path goes for eternity.’ This represents ‘the territorial and human consequences of a border’, to echo the

words of William Van Schendel.

Thus, the Bengal border, as depicted in partition stories, is often huge as well as ‘impossibly long’. But there is an ironic dimension to the border as well: the border is porous and fragile—fragile like the body of Fazila in Sohrab Hossain’s ‘Between the Borders’, who knows that women like her have to yield now and then to the ugly desires of professional touts or the BSF, or the BDR: ‘They had come to accept these professional hazards for the sake of livelihood, and to keep base life afloat for their children. They knew that it was necessary to extend such favours if their bundles were to cross borders.’ A woman’s body at the border is therefore cheap like her knapsacks.

In their Introduction to The Trauma and the Triumph: Gender and Partition in Eastern India, Jashodhara Bagchi and Subhoranjan Dasgupta observe that in both the divided states of Punjab and Bengal, ‘women (minors included) were targeted as the prime object of persecution. Along with the loss of home, native land and dear ones, the women, in particular, were subjected to defilement (rape) before death, or defilement and abandonment, or defilement and compulsion that followed to raise a new home with a new man belonging to the oppressor-community.’

This statement is based on historical truth. Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (2000) and Joya Chatterje’s The Spoils of Partition: Bengal and India 1947–1967 (2007) bear testimony to it. Regarding the fictional representation of the ‘spoils of partition’ we would like to refer to two stories: Hasan Azizul Huq’s ‘The Exile’ and Ahana Biswas’s ‘A Mother Divided’. In the first story, the portrayal of violence is gruesome. The reader may remember that section of the narrative where Bashir wildly runs to rescue his near and dear ones from the clutches of the criminals but to no avail:

The house has already been gutted to nothingness. They are gone. Bashir’s seven-year-old son, pierced and stuck to the earth by a spear and the body of a twenty-six-year-old woman, looking like a black, burnt piece of wood, were there in the ruined gutted house. The air was heavy with the foul smell of raw flesh burning.

So, the story shows that the perpetrators of violence targeted mainly women and children, although old fellows like Wazddi could not escape from their bloody grip either. The portrayal of communal violence in the narrative sends a chill down our spine. ‘A Mother Divided’ is a cruel story of ‘defilement’ of a Hindu woman at the hands of ruffians in the backdrop of Noakhali riot followed by the ‘abandonment’ of the woman by her husband. The story, however, goes beyond the set pattern and shows that a man ‘belonging to the oppressor-community’ rescues the woman when she is on the verge of committing suicide. The new man gives the woman shelter and protection. But the scar of trauma is not healed up. It surfaces when she sees her son and daughter-in-law after a long while. She cries out, ‘I feel scared… I am terribly frightened of menfolk’.

Bengal Partition stories sometimes represent the horrible aspect of gendered violence. A clear example is ‘Jatayu’ where Durga, a victim of communal riot, narrates her traumatic experience through a kind of stream of consciousness technique: ‘And when the sky was smitten with the sound of azan they took me out in the field, laid me there on the ground in the light of the burning house. My mother was laid by my side. And a hand started to squeeze my breasts.’ This ‘hand’ becomes an unidentifiable source of fear and continues to haunt the psyche of this woman and makes her restless. While speaking of different forms of violence that accompanied Partition, Meghna Guha Thakurta writes, ‘What is crucial to note is that violence also typifies a state where a sense of fear is generated and perpetrated in such a way as to make it systematic, pervasive and inevitable.’ This is exactly what happens here because the ‘hand’ leaves no moment of peace for Durga. She feels, …‘there is no escape for me. Slowly a hand will raise its finger, point at me and tell she is here; it is that woman.’

Violence, however, is not a major dimension of the human experiences in Bengal Partition stories as it is in the stories from Punjab. Stories from Bengal are ‘relatively free

from violence in its crude form’. But these stories, on the other hand, articulate the idiom of ‘a loss of a world’—a world in which Hindus and Muslims lived in amity and harmony over generations. Partition shattered the fabric of peace and unity overnight, ‘signifying the death of the social’, to use a telling expression of Dipesh Chakrabarty. It is just ‘inexplicable’ and bewildering how ‘neighbours turned against neighbours, friends took up arms against friends’.

Jyotsnamoy Ghosh’s ‘The Bait of a Dice’ poignantly portrays this ‘inexplicable’ situation involving the sudden breakdown of communal harmony. But the story is open-ended and its ending seems to contain a positive note. Bula, the victim of ‘Partitioned Bengal’ (to echo the original title of the story), does not lose self-confidence when she is deserted by her parents. She writes to her mother from a spot ‘where the borders of the two countries have merged’, that she has ‘an invitation from a loving heart’—from Firoj—to go back to him when she has none to look forward to, and she believes that she will have ‘the strength to respond to that invitation someday’. Bula, therefore, attempts to triumph over her trauma by her resilience.

This excerpt from ‘The Bleeding Border’, edited by Joyjit Ghosh and Mir Ahammad Ali has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from ‘The Bleeding Border’, edited by Joyjit Ghosh and Mir Ahammad Ali has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.