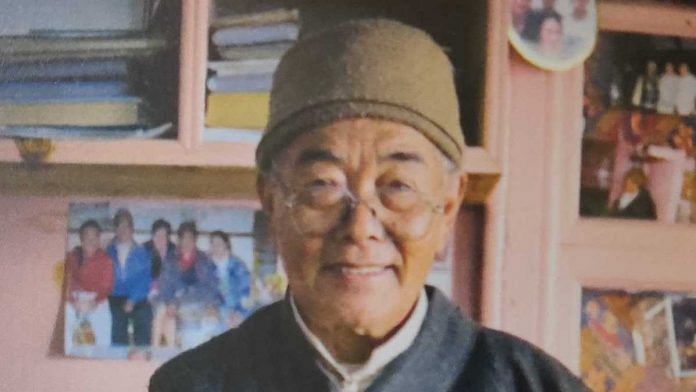

Sometime during the last months of 1952, 19-year-old Kanchha Sherpa was grazing a herd of yaks in his hometown of Namche Bazaar, a village situated at an elevation of 3,400m (11,200ft), which is now popularly known as ‘the gateway to Everest’.

Stricken by poverty and with no livelihood options to hand, Kanchha must have been wondering how he would eat that evening. Just then, he saw a couple of Sherpas dressed in western-style jackets and boots, possibly members of a Swiss expedition team who attempted to summit Everest in 1952.

Curious, Kanchha approached them and asked where they had found their outfits. The men told him that they worked for Tenzing Norgay Sherpa in the city of Darjeeling, the other side of Nepal’s eastern border with India.

At that time, Tenzing Norgay, who grew up in Thame, a small village near Namche Bazaar, was living in Darjeeling. He had already been part of six earlier attempts made on Everest. In a 1952 Swiss expedition, Tenzing Norgay and climber Raymond Lambert had almost made it, reaching up to 8,595m (28,199ft), an altitude record at the time.

Hearing about Darjeeling and Tenzing Norgay, and having seen these men wearing ‘nice’ jackets and shoes, Kanchha was easily lured. He reflected on his own life in Khumbu and said to himself, ‘I surely deserve better than this. If these men can, why can’t I?’ For Kanchha, his instant attraction to the Darjeeling dream was neither a result of the lure of adventure nor an expectation of money. All that he wanted was to escape the hardships of Khumbu and see what life had to offer. That same day, Kanchha ran away from home and, after four days of walking, found himself at the doorstep of Tenzing Norgay’s home in Darjeeling.

Also read: Liquor bottles & food cans among 11,000 kg of trash found on Mt Everest

When Kanchha introduced himself, referring to his father whom Tenzing Norgay knew from Khumbu, it became easy to find a place in Tenzing Norgay’s home. For the next three months, Kanchha helped out with household affairs – cooking and cleaning. One fine morning, Tenzing Norgay offered Kanchha an interesting job. He wanted him to take some khaireys (local slang for ‘white people’) to ‘Chomolungma’, the locals’ name for Everest, named after the Tibetan mother goddess of the world.

Interestingly, Kanchha did not know, at the time, that Chomolungma was the highest mountain on the planet. He felt instantly thrilled – not just because he now had a well-paid job that brought him 8 rupees per day (US$0.066 by the current conversion rate), but also because he would get to meet pale-skinned foreigners for the first time in his life.

The team of Sir Edmund Hillary assembled in Kathmandu two days after Kanchha and Tenzing Norgay arrived. Kanchha recalls Sir Edmund Hillary as an extraordinarily tall person with brown hair and blue eyes.

The topography of Everest was as new for Kanchha and most of his fellow Sherpas as it was for the group of British climbers. None of them had any idea how cold it was going to be up there, how difficult the terrain would be or how they were actually going to climb the mountain. All that they knew from the 1951 British reconnaissance of Everest from the Nepal side was that it was altogether possible to take that route all the way up to the summit.

Only a few minutes after leaving the safety of Base Camp, Kanchha’s team came across a chunk of moving ice, something they had never seen before; they didn’t know that such things even existed in the mountains. That place, known today as the Khumbu Icefall, is a treacherous 695-m (2,280-ft) moving river of ice, riddled with shifting crevasses, starting at the Lhotse Face at around 7,600m (25,000ft). The Icefall creates a major obstacle for climbers en route to Everest from Base Camp to Camp 1, and some portions between Camps 1 and 2. It has so far claimed a quarter of all those who have died on the Nepali side of the mountain.

Also read: Nirmal Purja, the Nepali mountaineer who summitted Everest, Lhotse & Makalu in two days

The persistent Sherpas took around a week to figure out a viable route. However, there were still several deep crevasses along the way, and the expedition team had two ladders used for bridging the deadly gaps. ‘It was not practical to re-use the same ladders again and again on different crevasses, as it was time consuming as well as risky,’ Kanchha told us. Despite all their meticulous planning, including the purchase of sufficient supplies of gear, food and oxygen, the British team’s calculation of the required number of ladders had failed to match the eternal challenge on the face of Khumbu Icefall.

The team came up with the idea of using tree logs to cross the crevasses. The next problem, however, was that no trees grow at that altitude. The nearest possible location to get the tree logs from was Pangboche, a village at around 4,000m (13,000ft) that houses the monastery where Sherpas say their prayers before their ascent.

For religious reasons, the villagers at Pangboche would not let the expedition team cut any trees in the village, so the Sherpas had no option but to return all the way down to Namche Bazaar to cut down pine trees and then carry them back up to the Khumbu Icefall (it is about a week-long journey from Namche Bazaar to Everest Base Camp). Kanchha and his team carried nearly a dozen pine logs to the Khumbu Icefall and used them to bridge the crevasses.

Also read: Why winter ascent of Mt K2 by missing Pakistani, 2 others is such a hazardous climb

Despite successfully crossing the Icefall, Kanchha and the team of Sherpas still had a long way to go. The Sherpas were told that the higher they scaled the mountain, the higher their income would be; the heavier the weight they carried, the heavier the bag of earnings they would take home.

Throughout the entire scope of their mission, the duties performed by Kanchha and his fellow Sherpas were key to the well-being and success of the expedition. Leaving the main climbers Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay behind, it was the Sherpas who climbed further up from every resting point, with loads of about 25kg (55lb) on their backs. Their job was to figure out the way forward, find another resting camp at the higher altitude, cache all the supplies there and come back again to guide Hillary and Norgay.

When the expedition reached Camp 4, the Sherpas were already exhausted. Kanchha remembers that he and his fellow Sherpas were unwilling to go any further. During three days of rest at Camp 4, Tenzing Norgay did all he could to cheer the Sherpas up.

‘He made tea for us, gave foot massages and prepared us to go further up, encouraging us to continue exploring the way,’ Kanchha told us.

Three Sherpas, including Kanchha, went up to another point above 8,000m (26,247ft), spending the night there. The next day, they climbed further up and securely erected a small tent and dropped off oxygen bottles, food, sleeping bags and other gear for Norgay and Hillary. Crossing off that last job on their list was a big achievement for Kanchha and his team.

As Kanchha and his small group returned to South Col then further down, Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary were carefully approaching the summit. After spending the night of 28 May 1953 at the very last camp, the next morning Norgay and Hillary went the rest of the way and, in the words of Hillary himself, ‘knocked the bastard off’.

To this day, Kanchha still stresses his decisive role in the first successful summit: ‘Hillary and Tenzing followed my footsteps and slept in camps that we erected,’ Kanchha said. ‘I still wonder how they figured out the rest of the way up to the summit. To me it looked impossible from where I had last stood.’

After this, Kanchha went on other Everest expeditions with different teams. But each time he went up there, his journey ended at the last camp and, despite being a pioneer who paved the way for the first successful expedition, he did not get a chance to scale the summit himself. A couple of years later, Kanchha’s wife asked him not to go anymore, as they had already saved enough to open a hotel in Namche Bazaar.

This excerpt from ‘Sherpa: Stories of Life and Death from the Forgotten Guardians of Everest’ by Pradeep Bashyal and Ankit Babu Adhikari has been published with permission from Hachette India.

This excerpt from ‘Sherpa: Stories of Life and Death from the Forgotten Guardians of Everest’ by Pradeep Bashyal and Ankit Babu Adhikari has been published with permission from Hachette India.