The CBI was known as the Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) when it was created by the British in 1946. It derived its legal authority from the DSPE Act 1946. CBI officers derive their investigation powers under the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), the same law that lays down how police officers should conduct themselves while registering a crime, carrying out searches or arresting an accused, and launching similar action. This would mean that CBI officers were technically ‘police officers’ while exercising powers under the CrPC.

There is a serious infirmity here which makes the CBI dependent on the state governments to give consent to CBI officers for acting within a state. This is because ‘police’ is a subject that falls within the ‘State List’ embodied in the Constitution of India under the seventh schedule. Such consent can be blanket, empowering the CBI to investigate any case under any law in operation anywhere in the country. It could be partial and case by case, so that in every investigation the CBI should approach the state government concerned. This is a cumbersome procedure that not only slows down investigations, but robs a sensitive investigation of its secrecy, alerting the offender and allowing him the opportunity to tinker with available evidence.

Successive CBI chiefs had proposed to the central government that an exclusive CBI act should be passed, an act wherein CBI officers will cease to be called ‘police officers’, and will enjoy a status similar to customs, central excise and income tax, and exercise powers independent of state governments. Drafts prepared by these chiefs never saw the light of day. They are possibly gathering dust in the corridors of North Block that houses the Home Ministry (MHA).

If one ignored this operational shortcoming that every CBI chief faces, the job was interesting and challenging. You did not have to be brilliant. What the chief needed was a cool head and the utmost objectivity that he could bring to evaluating the evidence put up before him by his subordinate officers.

Also read: IAS officer Ashok Khemka says CBI lacks accountability, questions ‘Rs 800-cr annual budget’

On average, the CBI registers about 1,000 cases annually. In addition, there is the sizeable backlog of cases under investigation for several years. The director does not directly interfere in day- to-day work, unless a case has become controversial, requiring minute guidance and periodic reporting to a court.

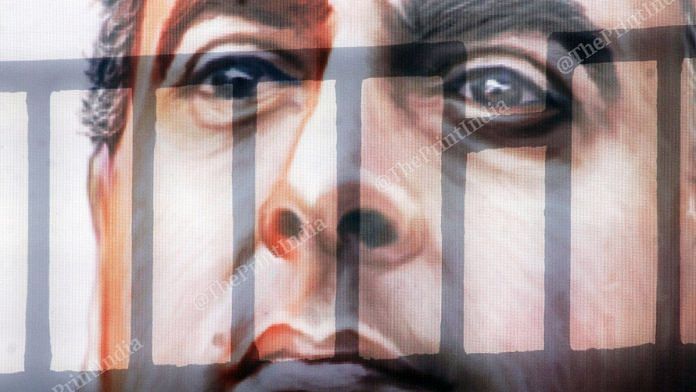

I inherited the legacy of some important cases which had been handled partially by my predecessors. Perhaps the most important of these was the Bofors gun deal in which the famous Swedish manufacturer Bofors AB was alleged to have given substantial bribes to politicians and civil servants in India to secure a huge contract. These included former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi; Octavio Quattrocchi, a middleman representing an Italian firm, Snamprogetti, and based in Delhi; Win Chadha, an agent for several armament manufacturers; and others.

Bofors is a fascinating story. The investigation lasted more than two decades, from 1987 to 2009. I came into it nine years after the First Information Report (FIR) was registered.

Fundamentally, this was a classic case of corruption involving an arms manufacturer/seller and a government buyer. There was nothing novel about the methods adopted by this particular arms dealer. Many leading figures in the corporate world have told me that no arms sale or purchase in any part of the world ever takes place without payment of commissions to middlemen.

What was different with Bofors was the high moral ground that the Government of India took, saying that middlemen were the fountainhead of corruption and they needed to be eliminated if a deal was to remain clean. The accidental discovery of such dubious intermediaries, who had played a prominent role in the Bofors purchase, put paid to the government’s claims that it had successfully got rid of agents. It was becoming evident that the principal actors of the conspiracy to make money, causing loss to the exchequer, were not unknown to those in government (read Rajiv Gandhi and his coterie).

In March 1986, a $285 million contract was signed between Bofors AB, the Swedish manufacturer of the internationally reputed howitzer gun, and the Indian defence ministry officials. The agreement contemplated the sale to India of 420 howitzers. What was apparently a straightforward transaction was aborted after the exposé—first by a Swedish radio station, and later by a Swedish newspaper, according to which Bofors AB had paid huge sums of money by way of bribes to Indian government officials and the ruling Congress party men. Greatly embarrassed by this news, the government moved to cancel the order and blacklist the company from any further bids in India. The case acquired huge political overtones and a battle ensued between the Congress party and the Opposition. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s defeat in the 1987 general elections was attributed to the Congress party’s role in the scandal.

Also read: Rajiv Gandhi – the ‘unwilling’ PM who laid the foundation of a modern India

A Preliminary Enquiry (PE) was registered in 1988. Two years later, a Regular Case (RC) was registered by the CBI on 22 January 1990, under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) for alleged offences of criminal conspiracy, cheating and forgery, along with sections of the Prevention of Corruption Act. The accused cited were Martin Ardbo, the then president of Bofors AB, and middleman Win Chadha (based in Dubai), and a few others.

Subsequently, in the course of investigations, the name of another middleman, Ottavio Quattrocchi, the Italian national who was an executive of Snamprogetti, based for some time in Delhi, and who was generally known to be close to the Gandhi family, was added.

A momentous and controversial step was the naming of Rajiv Gandhi in the charge sheet as an ‘accused not sent for trial’, because he was no longer alive.

In June 2002, the Delhi High Court quashed all proceedings in the case, an order that was reversed by the Supreme Court of India in July 2003. In February 2004, the CBI suffered another setback with the Delhi High Court quashing charges against Rajiv Gandhi and others. In May 2005, the three Hinduja brothers succeeded in getting the charges against them dismissed by the same court.

If the historic investigation did not ultimately succeed in court, it was because of several factors, the chief among which were the change of government in 2004 and certain questionable judicial rulings.

One must, however, remember that the CBI faced several constraints and obstacles. For every step in the matter of approaching the governments and courts of other countries, such as Switzerland, Malaysia and Argentina (the latter two countries being where Quattrocchi found sanctuary), the CBI needed the nod of either the External Affairs Ministry or the Department of Personnel (the administrative department for the CBI) or the Law Ministry. This was compounded by the perceived apathy of the Narasimha Rao government (1991–96) to the task of ensuring speedy progress in the CBI investigation. For instance, just before the CBI decided to arrest Quattrocchi, it is conjectured that he was tipped off by a senior member of the government, whereupon he fled the country and escaped from the long arm of the law.

Many persons, in and out of government, have, over time, asked me whether there was evidence of any payment made directly to Rajiv. My emphatic response has remained the same: there was not the slightest evidence to this effect. The big question mark was, and is, with regard to the moneys received by Quattrocchi and the Hindujas, both known for links with the Gandhi family. It is possible some of the payments were meant for the Congress party. It is difficult, however, to confirm this.

The Bofors case will remain an example of how a genuine case can be deliberately sabotaged by a government run by a party which has a lot to hide from the public. The guilt here rested squarely on the shoulders of those who controlled the CBI in the 1990s and later during 2004–14. If the CBI registered a PE (preliminary enquiry) in 1988, it was solely because of the huge public furore created by the Swedish Radio and Hindu disclosures. The government led by Rajiv Gandhi had no option but to do a thorough investigation, even if it meant an unobtrusive ‘operation whitewash’. The judiciary at the middle level was a willing accomplice, and its ‘holier than thou’ claim here was almost a charade.

Also read: Should SC revisit Rafale case after The Hindu story or not have heard the plea at all?

The CBI has come under attack by armchair critics. Let us face facts. The CBI’s autonomy, in principle, is extremely limited and confined to cases without any political undertones. Yet, many cases referred to it for investigation, like the 2G case, have somewhere a political link. How does the investigating officer then stave off political pressures? This lamentable state of affairs will continue, given the kind of democracy we have. According to some, this curb on the CBI is justified so that no one CBI chief is in a position to overstep his limits and cause embarrassment to a popularly-elected government. How can we take exception to this argument, when we have had at least two recent instances of moral turpitude at the top CBI leadership?

This excerpt from ‘A Road Well Travelled’ by R.K. Raghavan has been published with special permission from Westland Books.

Excellent…?

One minor MistakeRajiv Gandhi lost d Elections Not in 1987 ? .. but in 1989 ?

Shekhar sir ? Writes So Well, I have to Read it Carefully..

.?