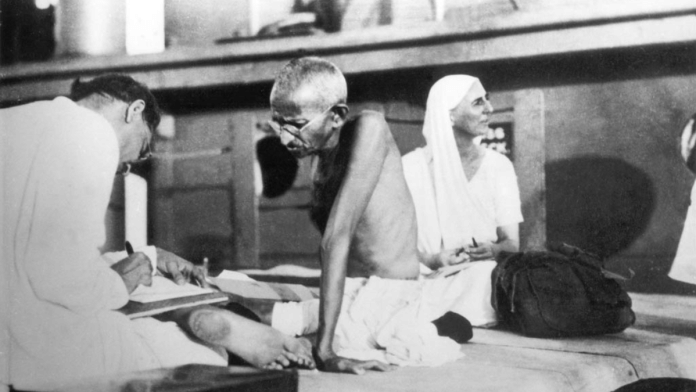

In the prayer meeting on 8 October, Gandhi addressed some structural manifestations of a society engulfed by hate, for instance how the media becomes a propaganda machinery. To begin with, Gandhi returned to the subject of friendship:

‘We don’t want to go into the question of who is more guilty and who less, or who started it. In my view that would be sheer ignorance. That is not the way of becoming friends. If those who were enemies till yesterday want to be friends today, they should forget the past enmity and start behaving as friends. What is the point of remembering animosity? There can be no friendship if people think that they would be prepared to fight if necessary but would remain friends if they could. That is not how true friendship grows.’

Gandhi holds that looking for the origins of a quarrel in order to hierarchize guilt was an ignorant way to propose the possibility of friendship. The second criterion for a possible friendship is the forgetting of past enmity. The memory of strife does not serve the cause of friendship. In fact, memory can only cause hindrances. Forgetting is the price to pay in the politics of friendship. Gandhi adds a strict third criterion: friendship can’t be based on a vacillatory promise.

Gandhi took on the press next. First he laid down the general principles and limits of the freedom of press:

‘When there is freedom, there can be no restrictions on the Press regarding the reports and the news to be published. But public opinion can be very useful at such times. When the newspapers do dirty propaganda or publish unfounded reports or incite people, the Government should come down on them to put an end to these or take legal action against them. But in doing so the riot situation worsens and there is more trouble. The Government cannot resort to that course… Today all the correspondents, editors and owners of newspapers must become truthful and serve the people. No false information should appear in the newspapers nor should they publish anything that would incite the people. Today, when we have become independent, it is the duty of the public not to read dirty papers but to throw them away. When nobody buys those papers they will automatically follow the right path.’

Also read: How Nehru combated anti-India sentiment in West Asia—distanced himself from Israel

Gandhi was a journalist besides being a political leader and reformist. He does not think of setting limits to media freedom through constitutional law, but through public opinion. The morality of public culture must be able to judge any deviance in media guidelines. Gandhi considers governmental intervention through legal action necessary if media indulges in propaganda that may disturb social peace. But he does not find it a useful deterrent during moments of social or political crisis. Curbs on the media in such situations might worsen the circulation of fake news. Gandhi lays a lot of onus on public responsibility.

His thoughts are extremely relevant today as press freedom in India is currently mired in propaganda for the ruling regime. Media ethics has been compromised by efforts to turn readers and audiences into collaborators of power.

Gandhi described the specific issue he was responding to that caused him consternation:

‘I feel ashamed at the fact that today people have got into the habit of reading dirty and undesirable things. Such newspapers are widely circulated. I read about an incident at Rewari. A newspaper published a report saying that the members of the Meo community killed all the Hindus, set fire to their houses and looted their property and cattle. I was shocked to know that the Meos had indulged in such terrible things. The next day there was no information about Rewari in the papers. It was all a cooked-up story. I wondered how that news about Rewari ever came to be published in the paper. I would like to say that the man who wrote about the Rewari incident should give an explanation. He must explain whether he had written that story on wrong information or it was deliberate mischief. He is guilty of great crime before God.’

Spreading misinformation either by publishing unverified facts or motivated by a political agenda is a crime, particularly in situations of strife. Journalists indulging in such activities are accountable to their job as well as to the people.

This excerpt from Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee’s ‘Gandhi: The End of Non-Violence’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House.

This excerpt from Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee’s ‘Gandhi: The End of Non-Violence’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House.