Doctor-X (to Lily): Maloom hota hai ye ladka abhi tak poori tarah tumhare bas mein nahin hai.

Lily: Nahin boss, mere bas mein hai.

Doctor-X: To phir ise apne gharwalon se itni mohabbat kyun hai?

Doctor-X (later, to Madam): Lily (se) na ho to aur do chaar ladkiyan is ke raaste mein daal do.

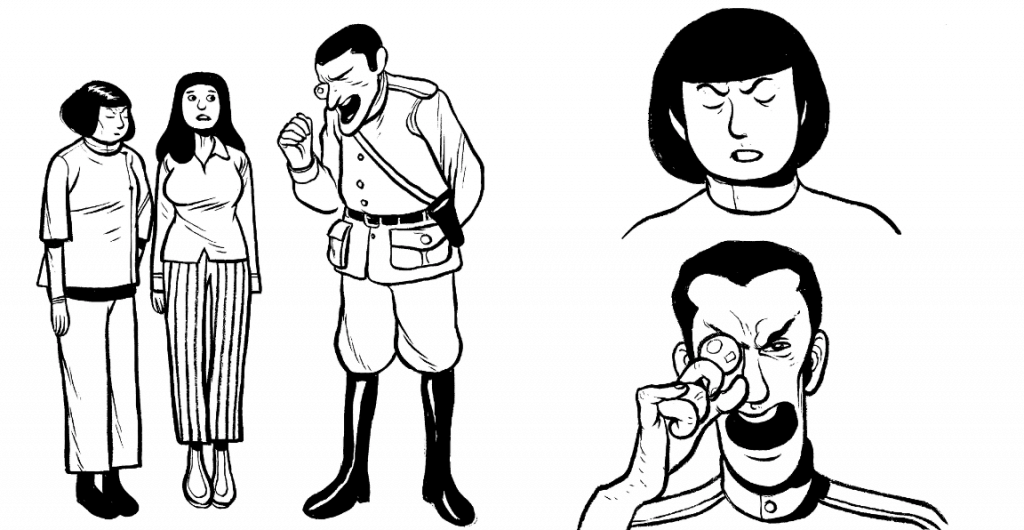

Doctor-X ( Jeevan) is the principal villain in the 1968 diamond jubilee hit Hindi film Ankhen. Lily (Daisy Irani) is one of his young female assistants. Madam (Lalita Pawar) is an older and senior aide. They are talking about a (Muslim) young man who is betraying his family, working for foreigners out to wreck the peace and progress of the motherland. However, unlike what the dialogues seem to suggest, the film’s baddies are strangely asexual in their conduct, with a subtle wink here and a discreetly exposed femoral skin there drawing zero attention or passion.

In fact in Ankhen it is mostly the good girls who dress up sexy – e.g., Mala Sinha as Meenakshi, whose ample ‘princess’ bosom shows to advantage in the scene at the Sheikh’s Dariya Mahal. Yet it draws no discernable appreciation from the bad guys.

Doctor-X has a hoarse voice, looks vaguely far-Eastern, speaks in a version of Urdu/Hindustani at once refined and foreign, sports a monocle and is dressed in the fashion of a high-ranking Nazi military functionary. Lily (child-like – looking not menacing, rather silly – Daisy Irani was a major child star once) has what seems like a yellow striped night-suit on her. The poker-faced Madam boasts of a steel-grey androgynous outfit (in the sartorial style of China’s then contemporaneous cultural revolution) and an equally unforgiving formal hairdo on top.

Villainy in Ankhen is a fantastic pastiche of our pet fears, born out of a merrily fertile bourgeois imagination. Sex, and non saari-clad women, are malevolent agents, and thus made unattractive and mechanical. Filial feelings naturally cannot be understood by the enemy. The ‘Eastern’ adversary is unsurprisingly Chinese (given the 1962 Sino-Indian war and the memory of the humiliation suffered therein) and his attire a time-and-topography- challenged cocktail of Chairman Mao and Hitler. This being the height of the cold war, the ‘commie’ colour red features prominently in the proceedings, both public and private.

Gratuitous precision is something of an obsession with the villains in Ankhen. Thus, Doctor-X, secretly transmitting to his partner-in-crime, Captain (Madan Puri) on board the ship bringing in the contraband munitions, warns:

Hello Captain! Abhi abhi khabar mili hai ke tumhare jahaaz par Hindustan ka ek jasoos tumhara peecha kar raha hai. Uska naam Salim hai, rang uska gandami hai, kad hai uska paanch foot saadhe saat inch; uski aankhon ka rang hai dark brown aur hamein khabar mili hai ke tumhare sab saamaan ki talashi le chuka hai. Over.

One wonders whether the good Doctor is instructing the Captain to search for a gatecrasher or a groom?!

Later in the film, Tiger (aka Saeed), Doctor-X’s henchman in Beirut, has his men shadow hero Dharmendra’s movement.

Lookout-1: Sir wo kaali gaadi mein baith kar highway pe gaya hai.

Tiger to Lookout-2: Karim – Highway – Kaali Gaadi. Peecha karo.

Tiger has an instinctive faith in the visionary skills of Karim, which is quite touching – all he needs to spell out is the colour. Karim will somehow sniff out the target vehicle from the mass of black cars populating Beirut’s highways. And so he does!

It’s another matter, though, that Dharmendra outsmarts him through a judicious use of a reversible coat, a sticky tache and an expensive secondhand fez. (It’s interesting to see Beirut being featured as a swish, slightly equivocal location for Tiger’s shenanigans. Soon, in 1975, the

Lebanese civil war would plunge the Mediterranean resort town into a one-way street of fratricidal death and destruction).

The villains in Ankhen have technology on their side – sliding wooden doors mysteriously (and vociferously) open at the press of well-hidden buttons, to reveal panels of blinking lights, switches and meters. Young women (with Christian sounding names like Rosy), ‘man’ these emplacements, with an irresolute mix of ennui and attention. Serpentine underground passages leading to Doctor-X’s gloomy secret den (opening at one end inside a hospital; on the other onto a hill-top Hindu shrine – both violating codes of the sacred) are fitted with intruder-sensitive lights and the whole subterranean complex is wired to self-destruct (in the unlikely event of defeat).

Automated steel-spiked doors moving in for the kill come in handy in terrorising the virtuous mother/sister into submission, while a stethoscope-like tracking device helps Madam (in the disguise of a fastidiously religious widow) identify sources of inimical wireless signals.

She herself irreverently uses the hollow base of a Lord Krishna statuette to plant a spying transmitter in turn.

Ahead-of-its-time advances in prosthetics help create face masks that impersonate with credulous ease while sleek fiberglass speed boats fashion the obligatory chase in the bay, suitably a la mode.

This excerpt from Purab aur Paschim: Colonials, Neighbours and Others has been published with special permission from NID Press.