Like many significant religious and cultural texts, the Gita is often praised for the applicability of its wisdom to society across time and space, with the enduring popularity of the book invoked as proof of the universal relevance of what the text has to say about the human condition, a message that presumably applies to humans in all their diversity. But the Gita is rooted in a world in which modern notions of equality and rights were alien as were the modern ideal of citizenship and the idea of the individual as the sovereign author of his or her life story.

The vision of humanity articulated in the Gita is yoked to a divinely sanctioned model of caste and the patriarchal family. The unequal order of things in this material world is an embodiment of the cosmic order. A harmonious consonance between matters on earth and the divine world is essential for social stability. The Gita’s messages of universalism may resonate with modern notions of inclusion, but the text also endorses caste inequality and, by extension, the general principle of inequality. If Gandhi found in the Gita the resources for a universal theory of good versus evil and an overarching philosophy of life, for Ambedkar the text remained politically regressive in its valorisation of the inequities of the caste system.

Even if one were to assume, for the sake of argument, that one could work through and reconcile the contradictions of the Gita and see it as a manifesto for the dignity and honour of all human beings, or as a statement of norms by which all humans are to be judged, how would any such reading square with the legacy of caste violence that has been a permanent stain on Indian history? Or, how would such a reading hold as valid, given the history of blatantly exclusionary actions of the postcolonial Indian state, which have reached a crescendo in the past few years? The defence of the Gita’s universality, after all, frames it as a uniquely Indian philosophical-ethical statement about the nature and complexity of human beings. If this is indeed the case and if the text is as prominent in Indian life as widely acknowledged, what would explain the gap between the values in the text and the less savoury aspects of the social reality which the text is meant to inform and reflect?

Also read: Mahabharata to Modi — How India lost the space for moral dilemmas

For Indians and observers of India, there is another urgent question raised by the universalism of the Gita. Granting that one finds in the Gita an impulse towards equality as well as its opposite, and granting that the text possesses sufficient semantic plenitude for competing interpretations, why has Gandhi’s vision of the Gita—or his vision of Hinduism, for that matter—not been as influential in present-day Indian politics and society as has the weaponisation of iconic, highly visible symbols of Hinduism, including the Gita, through the project of Hindutva or Hindu nationalism? Adherents of Hindutva or Hindu nationalist ideology see absolutely no contradiction in invoking the Gita as proof of their universalism while expressing the most hostile sentiments towards Muslims, Christians and Dalits. On Twitter and Facebook, any number of accounts that identify themselves as Hindu, signalling their adherence to the faith with messages from Hindu texts as part of their profiles, unrelentingly spew bile against minorities, liberals, secularists and anyone that they term ‘anti-Hindus’. For all its ubiquity, for all the universality of insight about the human condition that is attributed to it and for all its emphasis on the idea of dharma, that is, moral obligation or ethical duty, the Gita, it would seem, has not necessarily contributed to widespread social transformation with regard to caste, gender equality or communal harmony, though it may have undoubtedly led to many individual acts of compassion or been inspirational for any number of people.

Such tensions between the universalism professed in the text and the realities of patriarchy and caste in the Gita and the Mahabharata are not unique to the Indian context or these works. Texts from other religious and cultural traditions, whether the Bible or the Qur’an, bear the same contradictions with regard to the rights of women, non-believers or non-members of the faith. Democracy and slavery coexisted in the world of ancient Greece; the Enlightenment project and its progeny, including Western liberalism, could live comfortably, even harmoniously, with slavery and colonialism from the seventeenth through the twentieth century; and in the twentieth century, nakedly imperialistic invasions and occupations have been carried out in the name of protecting human rights, often resulting in the death of several orders more of lives than they were meant to save.

At the very least, then, it is an open question whether the universalism of the Gita is able to transcend its endorsement of the hierarchies of caste and family or whether these hierarchies subvert and compromise the universal value of the insights of the Gita. In light of our expanded understanding of difference, diversity and inclusion, it is legitimate to inquire whether a nonmodern and pre-modern text like the Gita can genuinely speak to modern notions of identity and difference that are intimately tied to equality, rights and justice.

Yet, the politics of difference in the Mahabharata are less straightforward than appears to be the case at face value. Given its sprawling nature and digressions, its status as an open-ended text that has gathered stories in its fold through historical accretion, and its many versions, the Mahabharata also offers a basis for critiquing caste norms, patriarchal gender relations, and violence while it endorses the same. The well-known parable of Eklavya richly illuminates this polysemic complexity of the epic.

Eklavya was a Nishada prince who desired to learn archery. He approached Dronacharya, the teacher of the Pandavas and Kauravas, in the hope that the learned guru would take him as a disciple. Dronacharya refused since Eklavya was not of royal blood. Undeterred, Eklavya built a clay statue of Dronacharya, and, using the idol as a proxy for the teacher, mastered the art of archery. It so happened that Eklavya’s talents came to the attention of Arjuna. Threatened by Eklavya’s abilities, Arjuna voiced his displeasure to Dronacharya, accusing his teacher of reneging on his promise of making Arjuna the greatest archer in the world. Seeking to get to the bottom of the matter, Dronacharya asked Eklavya to reveal the identity of his guru, only to hear the young man take his name. Revealing Dronacharya’s statue to the master, Eklavya explained that he had taken the statue to stand in for Drona himself and had accordingly practiced his craft. To keep his promise to Arjuna and to ensure Arjuna’s supremacy in archery, Dronacharya asked Eklavya to cut his thumb off and offer it to him as gurudakshina, the offering given to a teacher in respect and gratitude. Without hesitation, Eklavya complied with Dronacharya’s request.

Also read: Bhagavad Gita wasn’t always India’s defining book. Another text was far more popular globally

The parable of Eklavya stands as a critique of the caste order and of the idea of innate Kshatriya nobility or dharma that Arjuna and Dronacharya are meant to possess. Eklavya’s sacrifice is lionised as proof of his noble and pure devotion to Drona—whose clay statue Eklavya has taken as proxy for the great teacher and guru—but what it speaks most loudly of is the ignobility of Arjuna, the prince and warrior.

Eklavya’s story, in sum, stands as a withering indictment of caste hierarchy privilege as literally impairing and socially disabling, a two-pronged destruction of the marginalised caste self.

The violence relentlessly meted out to Dalit bodies in postcolonial India relives this dual act of literal and social impairment and disability over and over again. There may be no willing Eklavyas in India today, but the idea of innate caste superiority and inferiority retains its hegemonic status among large groups of Indians, despite the increased assertiveness of Dalit groups and communities.

In the present world, as in the world of the Mahabharata, the question of difference remains fundamental to identity and is equally inseparable from the matter of rights. The Mahabharata, of course, was not part of a world in which an ideal conception of selfhood would necessarily involve an engagement with a formally articulated framework of human rights. Yet, like any number of pre-modern and nonmodern texts that deal with human suffering, violence and inequity, it does tread into the realm of what we now recognise as a discourse of rights. The denial of freedom, the oppression that is based on social status and position, the violation of the sovereignty of the self, as in the case of Eklavya, Draupadi and other characters in the Mahabharata—all of these intimately mesh together matters of difference, identity and rights.

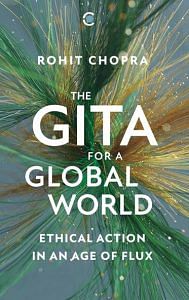

This excerpt from The Gita for a Global World: Ethical Action in an Age of Flux’ by Rohit Chopra has been published with permission from Westland.

This excerpt from The Gita for a Global World: Ethical Action in an Age of Flux’ by Rohit Chopra has been published with permission from Westland.