Virtually all of both what we call Buddhist art and Buddhist inscriptions from Āndhradeśa or elsewhere in India originated in or was found at a monastery, and yet the Indian Buddhist monastery is still not very well understood. There are, for example, still numerous misconceptions about how these places worked and to whom they belonged, about the permanency of their populations and how they paid the bills. There is even some doubt about what to call them. The most common term for what we call a “monastery” is vihāra, and here the trouble starts. “Monastery” may not be the best translation for vihāra since vihāra originally meant, and continued to mean, almost the opposite of a permanent, stable residence. It referred to “walking for pleasure or amusement, … sport, play, pastime … a place of recreation.”

In Jain usage vihāra still refers not to a permanent place of residence for Jain monks or nuns but rather to their wandering, their “continual journeying from place to place.” Indeed, the buildings that Jain nuns and monks stay in—they do not live there—are typically called upāśrayas, a term that Paul Dundas defines as an “ascetic lodging house maintained by the laity.” Typically, moreover, these “lodging-houses” are not simply maintained by the laity, they are also owned by them, and there is strong textual and epigraphical evidence that Buddhist vihāras also continued to be owned, more often than not, by what we call “donors.”

Epigraphically, this may be most clearly expressed in the title vihārasvāmin, if the latter means what it appears to: “the Owner-of-the-Vihāra.” Laymen and women carrying this title are repeatedly encountered in inscriptions from the Middle Period, or the first through fifth centuries CE. At least one Buddhist Monastic Code, or Vinaya, also takes as a given the lay ownership of Buddhist monasteries and addresses some of the continuing rights of the vihārasvāmin and the monks’ obligations to him: his permission must be asked before certain things can be done, for example, and the monks are under obligation to use what he provides. On a daily basis, too, religious verses must also be recited in his name and for his benefit by the monks.

Misconceptions about monasteries

There are, of course, a number of other misconceptions that make it difficult for what we call the Indian Buddhist “monastery” to be understood, but there are two in particular that stand out. The first is a classic case of being misled by our own language. More often than not we speak about “monasteries” doing something or other, or of receiving or owning something, as if they were active agents. But Indian Buddhist canonical texts and inscriptions overwhelmingly do not. Donations, for example, in both are not given to a “monastery,” or vihāra, but to the monks or monastic community (saṅgha) staying in the monastery, or to the universal Saṅgha. In other words, in Indian sources vihāra refers only to a building or physical space and is not used interchangeably with saṅgha to refer to the monastic community. In India a “monastery” does not do, own, or receive anything, and quite often was itself owned by a layman or woman.

The second misconception has been even more distortive with regard to how Buddhist monasteries have been viewed. It is still commonly assumed or asserted that Buddhist monks and monastic communities did not engage in buying or selling, or in business and financial enterprises in monasteries in India. This assertion is almost entirely based on one interpretation of a monastic rule in what will probably turn out to be the least representative monastic code—the Pāli Vinaya. This rule was from very early on understood by European scholars to mean that it was an offense for a monk to engage “in any one of the various kinds of buying and selling.” But this is not what the rule actually says even in its Pāli version, which—like the others—is almost hopelessly vague, and probably intentionally so. What the rule says in the Pāli version is only that it is an offense if a monk engages in “various kinds of buying and selling,” without saying what they were, and it certainly does not forbid—as it is commonly said to—all buying and selling. The “in any one of” in the above rendering was added by the English translators. One, however, does not have to look far to find a different interpretation of the same basic rule.

Sanctioned commerce

The Mūlasarvāstivāda-vinaya, an Indian monastic code that stands a much better chance of being more representative, presents a very different understanding of the rule. Its exegesis focuses not on buying and selling per se but on the motives for doing so, and in the process it intersects with what probably occurred on a regular basis in the cave monasteries in the Deccan, for example. D. D. Kosambi some time ago said in regard to these cave monasteries: “Certainly the yield of the villages assigned to the caves was not all used up for the monks who were in residence during the rainy season. It would be extraordinary if some of the grain were not sold to the caravans that began to pass by soon after the harvest.”

Strikingly, the Mūlasarvāstivādin monastic code has rules and regulations governing every step of just such a process: rules authorizing the acceptance and ownership by the saṅgha of villages and fields; rules authorizing the monks to rent out the fields for a share of the harvest; rules for transporting the grain to the vihāra; and rules governing the sale of grain to passing caravans. The last set of these rules also delivers an example of this code’s understanding of the rule on buying and selling.

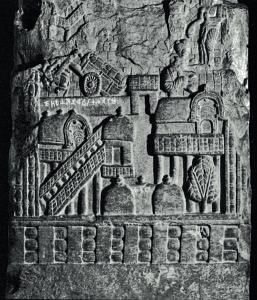

Here, a group of traveling merchants comes to a beautiful vihāra that had “high arched gateways” and was “ornamented with windows, latticed windows and railings,” and that “captivated the eye and the heart.” In response to the beauty of the place—and to that alone as far as we are told—the merchants want to provide a meal to the monks but do not have the necessary rice and say to the monks: “We will give you the price and you must provide us with rice.” The monks respond by alluding to their under-standing of the rule on buying and selling, saying: “since the Blessed One has promulgated a rule of training we cannot sell rice.” But when what they said is reported to the Buddha, it becomes clear that the monks have not understood the rule. He first orders that “when someone makes a meal for the sake of the Saṅgha you must thus sell him rice!” Then, when the monks sell strictly according to market price, the Buddha orders them to add a little something extra and thus sell under market value, in effect undercutting any competition; and then follow rules on how, in effect, to run an efficient granary. But the final provision under this rule is the broadest: “If a monk buys without seeking a profit, and if a monk sells without seeking a profit, in both there is no offense.”

This is an excerpt from ‘The Business Side of a Buddhist Monastery’ by Gregory Schopen in ‘Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India’ by John Guy, published by Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad, in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Images copyright as listed under each image.

This is an excerpt from ‘The Business Side of a Buddhist Monastery’ by Gregory Schopen in ‘Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India’ by John Guy, published by Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad, in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Images copyright as listed under each image.