BJP, ruling party at the centre, says it is guided by the philosophy of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya. Congress member of parliament Shashi Tharoor, in his latest book ‘Why I Am A Hindu’, has described in detail how Upadhyaya managed to make his brand of nationalism a more acceptable one than contemporaries. Read an edited excerpt:

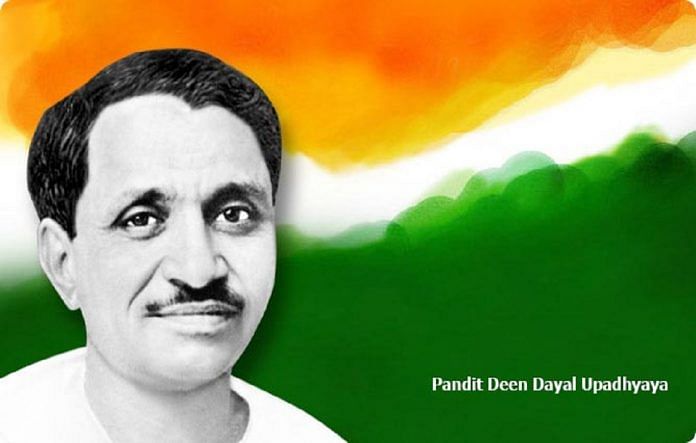

Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya is undoubtedly the most significant ideologue of the contemporary Hindutva movement. Despite having served only one year (1967–1968) as president of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the precursor party of today’s ruling BJP, before his life was prematurely cut short, Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya (1916–1968) is enjoying something of a renaissance these days. The Narendra Modi government ruling India since 2014 swears by his life and work, and there has been a proliferation of seminars and conferences discussing and dissecting his philosophy of Integral Humanism. Numerous institutions have been named after him, from the Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya Shekhawati University in Sikar (Rajasthan) to the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Hospital, Delhi and the Pandit Deendayal Petroleum University, Gandhinagar, Gujarat. Crores of rupees of government funds have been spent on various schemes and yojanas to perpetuate his name. There are medical colleges, hospitals, parks and a flyover (in Bengaluru) that bear his name, not to mention the Pt. Deen Dayal Upadhyaya National Academy of Social Security, Janakpuri, Delhi. The Antyodaya scheme of service to the poorest of the poor is said by the government to have been inspired by him. The ‘Make in India’ scheme is dedicated to him, or more precisely, ‘laid at his feet’. The Mughalserai railway station, where he died in mysterious circumstances at the age of fifty-two, has been renamed for him. The Deen Dayal Research Institute is reportedly ‘a hub of frenetic activity’, drowning under a ‘flood of queries from government departments’ trying to learn about Upadhyaya’s ideas, which are now expected to animate their work.

Upadhyaya’s writings and speeches on the principles and policies of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, his philosophy of ‘Integral Humanism’ and his vision for the rise of modern India, constitute the most comprehensive articulation of what might be described as a BJP ideology. The reverence in which he is held by those in power today and the near-deification of the man give him an intellectual status within the Hindutva movement second to none.

Upadhyaya saw his own thinking as flowing from that of Guru Golwalkar, the Sarsanghchalak of the RSS with whom he worked most closely. Golwalkar, in turn, was inspired by Vinayak (‘Veer’) Savarkar’s ideology of Hindutva. But whereas Golwalkar, with his desire to learn from Nazi practices, was judged too extreme for most mainstream opinion, Upadhyaya, who couched his ideas in moderate language, enjoyed broader acceptability. Unlike many ideologues, Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya was not just a theorist, but the leader of a growing political party and also its principal organizer. This created a curious paradox. As a political leader, it was imperative for him to respond to the day-to-day problems facing the party, critique government policies, issue and direct party propaganda, lead agitations, evolve the party’s electoral strategy and negotiate coalitions. His philosophy was thus the animating spirit of a life of practical action. Upadhyaya’s political role and values thus emerged from his philosophy, and the latter justified the former.

At the same time, the Jana Sangh of Upadhyaya’s day was not a realistic contender for power. Upadhyaya thus saw himself in the longer term, as a thinker whose role was, as one admirer put it, to project genuine nationalistic thought in the political sphere, well beyond the limited and short-term aim of the attainment of political office. One might even argue that had the prospects of power been more imminent, the president of the party might have spent his energies on more immediately attainable objectives, rather than abstract philosophical reflections divorced from his day-to-day tasks. It is possible to argue that the philosophy of Upadhyaya is the credo of man who does not believe he can ever have an opportunity to implement it.

But such a situation is in many ways preferable, because it means that the philosopher in question is not tailoring his thoughts to the expediencies of the political moment. In keeping with his circumstances, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya could afford the luxury—unavailable, say, to any of his counterparts in the ruling party—to develop his theoretical ideas in their pure and unalloyed form. Thus it is said by his admirers that Upadhyaya saw his political party as merely a vehicle to build a nation. Much of his philosophical thinking, therefore, focused on what constituted the Indian nation, and why, in his view, it had failed to become strong and unified. Upadhyaya saw this failure in moral terms—political corruption, the general public’s lack of any urge to make India strong and prosperous, a ‘degeneration’ of society and the fading away of the idealism that had inspired the struggle for freedom. Indians had misled themselves into equating freedom with the mere overthrow of foreign rule; this negative view overlooked the need for something far more positive, a genuine and patriotic love for the motherland.

Like Savarkar and Golwalkar, Upadhyaya too deplored the concept of territorial nationalism, which saw the Indian nation as being formed of all the peoples who reside in this land. In his view reducing the idea of India to a territory and to everyone on it elided fundamental questions that needed to be answered:

Whose nation is this?

What is freedom for?

What kind of life do we want to develop here?

What set of values are we going to accept?

What does the concept of nationhood really signify? A territory and its inhabitants, as Westernized Indians seemed to believe; this would embrace Hindus, Muslims, Christians and others under a common nationhood to resist British rule. This was a fallacy, according to Upadhyaya. ‘A nation is not a mere geographical unit. The primary need of nationalism is the feeling of boundless dedication in the hearts of the people for their land. Our feeling for the motherland has a basis: our long, continuous habitation in the same land creates, by association, a sense of “my-ness”.

The disappearance of the foreign power, Upadhyaya believed, had left a vacuum before a people accustomed to the ‘negative patriotism’ of anti-colonialism. Nationalism had to consist of far more than the mere rejection of foreign rule. Upadhyaya spurned the Western idea that nationalism as a political force was a product of the French Revolution and the situation created by it; he abjured the notion that a nation is made up of various constituent elements that can be itemized, such as a common race, religion, land, traditions, shared experience of calamities, means of transport, common political administration and so on. Such ideas, he believed, missed the essential ethos of nationalism—love for the motherland.

Since love for the motherland had never been inculcated in its inhabitants, their lives in independent India were now centred on money and greed—artha and kama in the classic quartet of human aspirations enumerated in the Purusharthas, at the expense of dharma and moksha. This modern materialism Upadhyaya saw as a major societal flaw. As he wrote in his book, Rashtra Jeevan Ki Disha (The Direction of National Life, Lucknow: Lohit Prakashan, 1971):

All our ailments in today’s political life have their origin in our avarice. A race for rights has banished the noble idea of service. Undue emphasis on the economic aspect of life has generated a number of lapses… Instead of character, quality and merit, wealth has become the measuring rod of individual prestige. This is a morbid situation… It must be our general approach to look upon money only as a means towards the satisfaction of our everyday needs: not an end in itself…this transformation in our attitude can only be brought about only on the basis of the ideals of Indian culture.

This is an excerpt from Shashi Tharoor’s Why I am a Hindu. No credits to the original writer???