It’s time for me to meet the head priest at this holiest of Bishnoi sites and have my questions answered. This is the equivalent of being brought deep inside the Vatican for a private audience with the Pope.

I expect grandeur. I’m led through a wooden gate and into a courtyard surrounded by a cloister. The floor is made of dirt. The surrounds are blackened plaster falling off walls to reveal bricks and slack mortaring beneath. To the left, a green cloth has been tied between the cloister’s pillars. Behind this cloth is Ramanand-ji, cross-legged on his cot. Now, in 2022, seventy-four years old, Ramanand has been Mukam’s high priest since 1985. He’s a solid man with thick arms, a balding crown and grey hair, his eyebrows dark and quizzical, and a thick moustache dropping down into bearded jowls.

I ask my questions.

‘Is Bishnoism a religion?’ I’ve been arguing that it is, I explain. Founders of religions tend to stem from other religions. Jesus was crucified as King of the Jews but Christianity is not seen as a sect of Judaism. The Buddha began life as a Hindu prince and left his palace to become a Hindu ascetic, but with its denial of gods Buddhism is clearly distinct from Hinduism. While Jambhoji preached that people should chant the name of Vishnu he spoke against the use of godly images, welcomed people of all religions, decried the caste system, created distinct rules to live by, made care for nature the dominant practice, established new rituals including ones of conversion, and brought in non-Hindu practices such as burial of the dead. Yet some Bishnois have kept correcting me. It’s a sect, they say. It’s a community.

‘Yes,’ says the high priest, ‘Bishnoism is a religion. It is not a sect. A sect is a path to a religion. A religion is universal, for the whole world. Hinduism is concerned for people. Bishnoism is concerned for the whole environment.’

Does he feel that concern for the environment is especially acute now, in an era of climate change?

The Bishnoi have been preparing for this for a long time. ‘Five hundred and eighty years ago,’ the high priest tells me, ‘Jambhoji knew what we are learning now.’

Other religions allow women priests. Might the Bishnoi go the same way?

He laughs. ‘Women are holy. We see them as the goddess Deva. We give them whatever they want, but they have never asked for this. I have never heard such a thing. They are busy doing what they do.’

Maybe in the future, in fifty years?

‘Who knows? I do know, from looking at some Hindu groups, that women pay more attention when the priest is a woman.’

Also read: Nalanda had a scholar at the gate to screen students. Only three out of 10 were admitted

I bring him my concerns about the story of Jambhoji and Rao Duda, when the young guru gave the prince a stick and told him to wield it like a sword. I’ve seen people worship the sword, I tell him. They believe the stick, as it was passed between the two men, instantly became that sword. Is that the meaning of the story, or is it a myth? I read the story as being one about confidence: carry the stick as you would a sword, have faith in who you are, and you regain your power.

The stick remained a stick, he believes. It did not turn, supernaturally, into a sword. ‘The stick gave him confidence!’

He does, however, believe in Jambhoji’s miracle at Rotu, where the area was transformed overnight with khejri trees big enough to drop shade over resting camels.

As regards Jambhoji’s teachings, though, here’s what is most important, Ramanand-ji says. Jambhoji taught us in his shabads that all his teachings must be taken as a whole.

You can’t pick and choose.

And I ask him about the young, who in the West at least are increasingly anxious about climate change. Should they be nervous?

‘They have lost their way, their dharma,’ he says. ‘They have lost their religion. They should take care of nature. They should take that as their religion.’

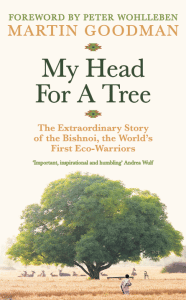

This excerpt from ‘My Head for a Tree: The Extraordinary Story of the Bishnoi, the World’s First Eco-Warriors’ by Martin Goodman has been published with permission from Profile Books/Hachette India.

dilip bro doesn’t understand how quotes work ??

Mr. Goodman comes across as a typical white man – eager to create divisions between Hindus in the name of sect and caste. His repeated emphasis on elevating the Bishnoi as a separate religion, apart and distinct from Hinduism, is a classic case of the white man stirring up trouble in Oriental societies.

If his interest is in preservation/conservation of the environment, why is he so hell-bent on depicting the Bishnoi as a separate religion from Hinduism?

It’s shameful that The Print provides a platform to the white man to indulge in his time-tested strategy of “divide and rule”.