Star TV was a foreign company with a capital F; it wasn’t just some nondescript, docile foreign outfit operating in a non-intrusive category. Star TV was owned by the despised, feared and ruthless Rupert Murdoch, who had an almost mythological reputation for gobbling up his competitors and changing the political complexion of countries in which he had major business stakes. His persona, or at least the way it was perceived, made life considerably more difficult for those of us who were having to deal with the naturally aggressive media—I was operating now from a position of weakness relative to our competitor. We had no viewership ratings and little mass appeal, as we were an English-language service. The much larger print media companies were all well-set organisations that partly wanted to befriend Rupert and partly wanted to run him out of business in India. Some people even went as far as to file PILs, or public interest litigations, against the company.

Legal notices were issued but couldn’t physically be served, as Rupert was neither listed as the owner of Star TV nor did he live in the country where the notices were to be served, though they did have the effect of preventing him from visiting India. Not that Rupert would have been much put out. He once said, as reported by the Observer in January 1978, that ‘The third world never sold a newspaper’. I wonder if he still believes that. Maybe he does, though I doubt it.

In 1993, the programming on the Star TV-owned and Star TV-distributed channels was all in English and of no help; rather, they were somewhat of a handicap. Star Plus screened the likes of The Bold and the Beautiful, Santa Barbara and Baywatch, which alongside MTV’s ‘racy’ music videos and young Westernised video jockeys, or VJs, were ‘proof ’ of Rupert Murdoch’s cultural invasion of India, of his intent to destroy Indian cultural values and corrupt the youth.

Also read: How Star TV became a dominant media force in India, top TV executive’s memoir reveals

The media was seemingly terrified of Rupert for a whole host of reasons, but mostly because they knew he could move into a position of considerable strength with politicians and, through that, manoeuvre political positions in the country. Fears that were not entirely unfounded as, in my opinion, given half an opportunity Rupert would have loved to get his hands on an Indian newspaper. Given the restrictions on foreign direct investment in the print and newspaper business in India though, he has never openly expressed such an interest.

BBC Worldwide, the BBC’s international news channel, was also distributed by Star TV. Everyone who is anybody knew fully well that the BBC was independent, but to muddy the waters and arouse public sentiment there was a lot of noise implying that Rupert was ‘controlling’ the BBC and its editorial content. This relentless barrage from the Indian media, in the form of negative newspaper headlines and opinion pieces, had a profound effect on the thinking within Star TV. I believe it was one of the major reasons why the Indian market continued to remain on the fringes of the overall business model for Star TV in Asia. The expectations were always modest, and whenever anything went well, it came as a big surprise to the senior executives in Hong Kong and New York. Whenever anything went wrong, or not as well as they would have liked, it was always a case of ‘Well, it’s India; what else would you expect? It’s a tough marketplace, after all.’

Such naivety was surprising but not entirely unexpected from a bunch of people who didn’t really know India or Indians at all, although they pretended to and occasionally paid appropriate lip service to wanting to get to know the country and people better. It took me a while to realise that many of these guys were not just ignorant about India, but also averse to accepting human differences—language, ideology, skin colour, education levels and even inclusive thinking. Today, many of them would probably be labelled racist, but twenty-something years ago, such closed-mindedness was sadly par for the course, whether it was aimed at the Chinese, the Indians or the Arabs. Many of these executives didn’t believe that the average Indian was anything other than lazy or corrupt, and in some cases both. So the general belief was that nothing much would come of India and that the real action and pot of gold lay across the border in Mandarin-speaking China. They were generally dismissive of and reluctant to follow through most of the ideas and proposals that came from India. Despite this, the India business continued to expand slowly but surely, and consequently grew its share of the overall Star TV pie.

However, Rupert himself didn’t share this perception of India. He could see the economic and social potential of the country very clearly by this stage. He had the highest regard for Dr Manmohan Singh, then prime minister, who had earlier, as finance minister, initiated the economic reforms that led to the emergence of India as a marketplace of significance. I’ve always believed that if Rupert could have found a way to get Dr Singh on his company’s board, he would have done so. Goodness knows he might still. Rupert is a man with incredible patience and staying power. Sadly, he wasn’t able to get all his other senior executives to share the same enthusiasm and vision about India’s prospects.

The big hope was always China and the gigantic marketplace that China represented. After all, that’s why Rupert had spent almost a billion dollars buying Star TV from Richard Li. Any business executive or banker will recognise that not only was that a great deal for Rupert and his company in pure geographical terms but in economic terms too. An average return per user (ARPU) yardstick would then and even now perhaps make buying Star TV a real steal, as it would have been less than one US dollar per Chinese consumer, and this without including the value of the other large markets available to the buyer, such as India, Indonesia, all of the Middle East, Taiwan, Korea and Singapore. It was almost a ‘buy one and get one free’ offer.

In India, Star TV and the programming on its channels had become a major talking point among both the glitterati and the intelligentsia. Conversations regularly centred around the excellent picture quality, the high-quality stereo sound and production quality of the channels. The on-air promos looked great and enticed Indian viewers to watch Pamela Anderson on Baywatch as she ran across their screens in her red bathing suit, plus the intricate plots of The Bold and the Beautiful, which brought intimate scenes of inter- and intra-family relationships and clandestine affairs to audiences in India who had never been exposed to stuff like this before on television. Was Rupert responsible for giving Indian audiences what they had wanted for some time but didn’t know who to ask? Was he the catalyst for social behavioural changes that were later localised by programme producers like Ekta Kapoor and others?

Of course, advertisers saw the merit in placing their brand messages alongside these programmes because they attracted the kind of premium, relatively moneyed audiences that were hard to find on the terrestrial broadcaster, DD. The proof of the pudding is in the eating, and obviously the Indian consumer was beginning to respond, to accept, to adapt and to adopt. Change and competition were now in the air. Competition for eyeballs was heating up and gathering pace. While the ad agencies were crunching their audience research numbers alongside the client’s product sales numbers, they would err on the side of caution, always being defensive in their decision-making, as they’re trained and prone to be. They had not factored in the value of the so-called ‘managing director’s wife syndrome’. Very often, the boss’s wife was watching Star TV and discussing the shows with her friends and family. Not only did the boss’s wife want to see her husband’s company’s ads on the programmes she watched, she wanted all her friends (and competitors) to see them too.

The late Parmeshwar Godrej— one of India’s most recognised and opinionated socialites and the wife of one of the country’s most accomplished industrialists, Adi Godrej—was one of the not-so-secret admirers of many of the shows on Star TV. She was known to have called Sam Balsara, the owner of Madison, the advertising agency the Godrejs used, to suggest that their brands seek to become sponsors of some of these contemporary, international shows. It didn’t take Sam long to get on the phone to us and put Godrej ads on Star TV channels. There was also the owner of India’s leading tyre manufacturer, MRF, in Chennai, who was a great supporter of sport and was making sure his MRF brand was on Prime Sport—be it cricket or F1 or Grand Slam tennis. Their advertising agency could not possibly consider dissuading MRF from being omnipresent on the Prime Sports channel. They were India’s largest advertiser on Prime Sports for a long time and because of being on a wide and internationally distributed channel, the MRF brand was seen in countries outside India, which generated new business opportunities.

Also read: How Google’s deals with Murdoch’s News Corp, other media could change how world accesses news

For the first time, there was pressure on the terrestrial broadcaster and by about 1995, their complete and total monopoly on the large Hindi viewership started to look to be in serious danger. The danger was from the new private TV stations: Zee TV, Sony and Star TV. And what perhaps was really galling was the fact that Star TV and Sony were foreign players. Star TV had seemingly slipped into the country’s vocabulary, largely by default (more on this later), before regulators had woken up to satellite television and seen its immediate and future impact. There were no laws regulating satellite broadcast, and the regulators had been clearly caught napping. It was much too late to reverse the trend, as by now millions of homes across the country had a satellite connection, popularly known as a ‘Star TV connection’. Star TV had occupied the space and become generic to the satellite category. To expect consumers now to switch off would be to ask them to go back to the dark ages and no government wanted to be the instigator of such an unpopular decision.

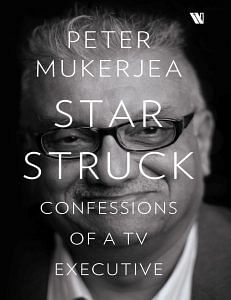

This excerpt from Starstruck: Confessions of a TV Executive has been published with permission from Westland and will be released on ThePrint’s SoftCover.

This excerpt from Starstruck: Confessions of a TV Executive has been published with permission from Westland and will be released on ThePrint’s SoftCover.