Hostility is not a memoir. Nor does it trace the history of Pakistan-India relations. It is, in large measure, about my tenure in India as Pakistan high commissioner from March 2014 to August 2017. It is my account of Pakistan-India relations during that period; the ups and downs that generated hopes and created stalemates; how the two sides dealt with them; why and how the bilateral relationship reached the present troublesome phase; whether there is any realistic possibility that the two countries would ever be able to become normal neighbors. In short, Hostility is not only about hostility between Pakistan and India but will also divulge how non-professionalism and personal grudges leave the art of diplomacy in disarray and, in turn, hurt state interests.

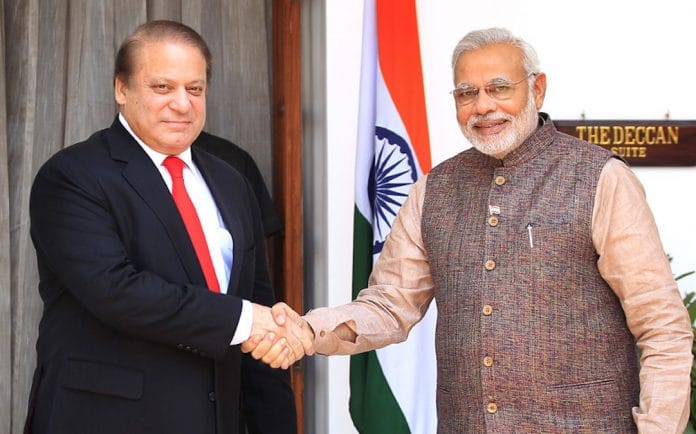

As the top Pakistan diplomat in New Delhi at the time when both Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Prime Minister Narendra Modi had made a very encouraging start with their first meeting in New Delhi on 27 May 2014, I do share some, if not total responsibility for the later developments on the diplomatic front.

Some in Pakistan and many in India continue to hold me responsible for not being able to build on the Modi- Sharif meeting. In fact, I am blamed, especially in India, for deliberately undermining the significant opportunities that had arisen. To them, I was uncompromisingly hawkish toward my host country and, perhaps, the most bellicose Pakistan high commissioner in India ever. Instead of contributing to building bridges, I was a source of exacerbating bilateral tensions, making sure that the initiatives taken to break deadlocks led to more deadlocks. In short, it was primarily because of me that Pakistan and India had not been able to take advantage of the bonhomie that the two prime ministers were able to generate and tried their utmost to retain even in the most difficult of circumstances.

Also read: Must fight together, PM Imran tells India as Pakistan offers ventilators, PPE as Covid aid

Some even suggested that I was working at the behest of the Pakistan establishment and worked in close coordination with them rather than pursuing the peaceful aspirations of the civilian leadership. Had I not been the Pakistan high commissioner during that time period, things might have been relatively better. I somewhat crossed my mandate by displaying excessive zeal on Kashmir. Whenever relations were looking to take a positive turn, I would throw in a monkey wrench. For instance, I should have avoided meeting the Kashmiri leadership which led to the cancellation of India’s foreign secretary’s scheduled visit to Pakistan in August 2014. Similarly, there was no point in my speaking in New Delhi about the issues related to the Pathankot incident which had created avoidable additional difficulties in the bilateral relationship. In a nutshell, I failed to serve the cause of normalizing Pakistan-India relations.

This book is not an attempt to clarify my position or put the entire onus of recurring setbacks on others and cast aspersions. Throughout my stay in India, I did what I thought was in the best interests of Pakistan and in sync with the strategic framework of Pakistan’s India policy. Even now, with the advantage of hindsight, I can say, with complete honesty and conviction, that I would not have conducted myself differently.

Diplomats, like other human beings, do come under pressure and, at times, do take decisions that may appear unintelligent and even undiplomatic. But how decisions are made is not always clear to outsiders. Thus, it is not uncommon to find analysts and experts forming and presenting their opinions driven by their own predilections and national prejudices.

At the public level, opinions are usually formed with half-truths and on the basis of what is shared or not shared by governments. Many developments taking place off-stage are made public to the extent possible, and rightly so, as diplomacy is not any other profession. Here, one is sometimes dealing with sensitive inter-state issues which require confidentiality even long after decisions have been made. Accordingly, I will still not be able to share many facets of our India policy and diplomacy as Pakistan’s interests take precedence over everything else. But Hostility will still reveal many inside details hitherto unknown to the people on both sides of the border.

Also read: Why PM Modi and Gen Bajwa mean business with India-Pakistan peace talks. Nothing else matters

People who are in the business of diplomacy know full well that there are multiple dependent and independent variables that shove and shape inter-state relations. When relations are deeply rooted in hostility and mistrust, the space for diplomatic maneuverability is discouragingly limited. Positions on issues are profoundly entrenched, and showing flexibility even at the tactical level, becomes hugely problematic and controversial. Both Pakistan and India have been facing the same dilemma almost from the very outset of their independence.

Over the decades, instead of resolving the Jammu & Kashmir dispute through a United Nations-supervised plebiscite, as pledged by the two countries, we created more issues and more cleavages. Resultantly, we fought wars, went nuclear and tried to undermine each other at all levels with the implacable mutual hostility continuing to be the major impediment in fostering regional cooperation.

South Asia remains the least integrated region in the world with intra-regional trade barely touching 5 percent of its total trade. Like other regions in the world, South Asia is also facing massive common challenges, ranging from terrorism to climate change to a worsening water crisis. But regional cooperation cannot be established and fostered in a vacuum. There is so much unpredictability in bilateral relations that the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), formed in 1985, is finding it harder and harder to realize its potential. So much so that it has now become hostage to confrontational Pakistan- India relations and is literally dysfunctional.

India is the biggest country in the region but it is not difficult to explain why it has not been up to the task. Though it claims to be the world’s largest democracy, the country’s internal situation and its external policies leave much to be desired in this context.

This excerpt from ‘Hostility: A Diplomat’s Diary on Pakistan-India Relations’ by Abdul Basit has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from ‘Hostility: A Diplomat’s Diary on Pakistan-India Relations’ by Abdul Basit has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

Another attempt by Pakistani establishment to down grade India as a democracy by a terrorist sponsoring state i.e. Pakistan.

He is a stupid guy who imagines himself on a horse with sword and riding onto DELHI.

He along with JIHADI ORYA MAQBOOL JAN and JIHADI laal TOPI discusses GHAZWA E HIND.

He is megalomaniac .

Saw your intervie with Karan Thapar and Najam Sethi. Najam Sahab took you apart very well. You were an employee of the govt of the day and meant to implement THEIR policies. You don’t have the luxury to decide if you agree with those policies or not.

Your anti-India approach is pathetic. You are now choosing to sell your book and take money out of India.

Why are wretched Marxists like Jyoti Malhotra in love with the enemy to give them space and spread their propaganda? The likes of Malhotra are a bigger threat to india than Pakistan, they are like termites eating away our own social structures from the inside.