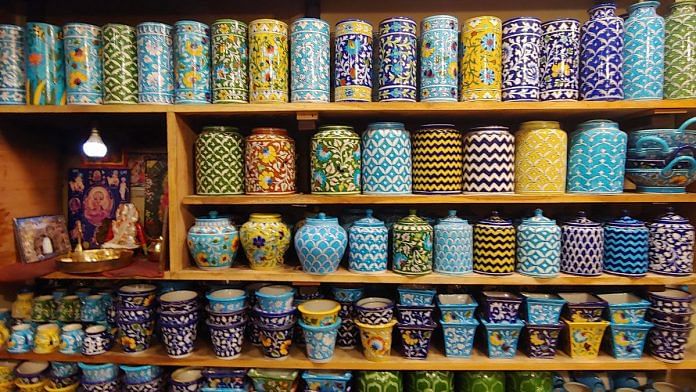

A type of ceramics produced predominantly in Jaipur, Rajasthan, blue glaze pottery is decorated with hand-painted patterns, often floral or geometric, set against a distinct blue background. Artisans produce a range of decorative and utilitarian products such as tiles, vases, bowls, cups, plates and even door knobs. Emerging in the nineteenth century, the designs found on blue glaze pottery in Jaipur were developed based on ceramics from the workshops of Delhi and Khurja (in present-day Uttar Pradesh) that were established during the Sultanate period (1206–1526). The industry later rose to prominence with the patronage of the Mughals. The impressive collections of the wealthy Mughals served as a reference point for the revival of the art. Their assorted chini-khanas, which housed collections of Chinese and Persian pottery, provided inspiration for the artisans. Many of the hand-painted designs found today are reflective of this foreign influence.

Introduced in Jaipur from Delhi and Khurja by the ruler of Jaipur, Ram Singh II, blue glaze pottery was promoted primarily under the aegis of the Jaipur School of Art, founded in 1866. Under the institute’s director, Opendronath Sen, the pottery was displayed at the 1883 Jaipur Exhibition, encouraging a rise in local production. However, years of waning patronage and the advent of modern technologies forced the art into neglect and decline. Successful attempts to revive the blue pottery industry were led by the social reformer Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and artist Kirpal Singh Shekhawat, with support from Maharani Gayatri Devi. Principal of the Jaipur School of Art, Kirpal Singh Shekhawat, took inspiration from artefacts in the Albert Hall museum as well as the decorative tiles that clad cenotaphs around Jaipur, to re-establish the region’s blue glaze pottery tradition.

Also read: Nandalal Bose built a visual & cultural national identity for India—with watercolours, linocuts

Each piece of pottery is prepared with great care, often with locally sourced materials. Traditionally, the moulding clay is made by passing ground quartz, glass, feldspar, and fuller’s earth or kaolin clay through a sieve and adding water to form a fine paste. The clay is kneaded to ensure uniform consistency, and is placed in moulds made of baked clay. The mould’s hollows are then packed with dry ash to help the intended object hold its shape, and then emptied out once the piece is removed and left to dry. The dry, moulded clay is then placed on a potter’s wheel where its surface is polished to achieve a smooth finish. If necessary, extra components may be attached to the piece using wet moulding clay.

The next stage is the glazing process. To make the first layer of glaze, finely ground stone, glass and flour are mixed with water to form a thick paste that is washed or painted on, and the object is subsequently placed to dry. The design is then applied onto the treated surface of the piece, rendered first in pencil and then with paint. The distinct blue colour is derived from jeypoorite and seypoorite, forms of cobalt oxides that were originally mined in the principality of Khetri (in present-day Rajasthan). While most blue glaze pottery is ornately designed, sometimes the entire surface may be treated with a mixture of copper oxide and gum to produce a solid turquoise colour.

However, blue and turquoise are not the only colours used while making this type of pottery. Other colours such as yellow — obtained by mixing lead and pewter, and yellow sandstone — and purple — obtained from a stone known as saind found in Bharatpur district in present-day Rajasthan — are also used to accent the pottery. More colours may be produced by firing metal oxides at high temperatures in the kiln. For example, iron may be used to make red, cadmium for yellow and chromium for green. Once the vessel has been decorated, a final layer of glaze is applied. This glaze is prepared by melting borax, vermilion and glass at high temperatures. Once the solution has cooled and solidified, it is pulverised into a fine powder and mixed with a flour paste to form a thick glaze solution. Once the entire vessel is treated with the solution, the object is baked in a kiln at 800-850°C for six hours. After baking, the vessel assumes a smooth and glossy surface, and is then cooled for about three days before it is considered a finished product.

Jaipur’s blue glaze pottery received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2008, and while the industry remains protected in Jaipur, several other workshops producing similar wares have cropped up in regions such as Chinhat near Lucknow in present-day Uttar Pradesh.

This excerpt is taken from MAP Academy’s ‘Encyclopedia of Art’ with permission.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit, online platform — consisting of an Encyclopedia, Courses and a Blog — which encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.