On 14 October 1956, Ambedkar and half a million of his followers took the momentous decision to exit the Hindu fold and convert to Buddhism. Behind the scenes of this massive event were a host of people involved in a flurry of activity for a smooth organisation of the mass conversion ceremony. What follows is an extract from Ashok Gopal’s magisterial biography of Ambedkar, A Part Apart: The Life and Thought of B.R. Ambedkar, in which the author tells us the little-known details of what transpired at Nagpur’s Deekshabhoomi.

The first definite announcement regarding mass conversion was made by the Bharatiya Bauddha Jana Samiti, the Buddhist Society of India, on 12 May 1956. Published in Prabuddha Bharat, the text contained a statement given to the Society by Ambedkar on the ‘desire for mass conversion’ expressed by his supporters. Ambedkar’s statement said the event would take place in October that year. He also told his supporters to celebrate the 2,500th Buddha Jayanti, falling on 24 May 1956.

In his address on 24 May 1956 at Mumbai, Ambedkar said the conversion would take place in the city, but four months later, on 23 September 1956, he issued this brief statement to the press from New Delhi:

The date and place of my conversion to Buddhism has now been finally fixed. It will take place at Nagpur on the Dussehra day, i.e., 14th October 1956. The ceremony of conversion will take place between 9 and 11 am, and in the evening of the same day I will address the gathering.

A key person involved in the choice of Nagpur as the venue and the subsequent organisation of the event was by Wamanrao Godbole, secretary of the Nagpur branch of the Bharatiya Bauddha Jana Samiti. Born in 1922 into a Mahar family living in a locality of Nagpur then known as Maharpura, he had been the chief promoter and organiser of the Samata Sainik Dal in the city in the early 1940s. Around 1942, he was introduced to Buddhism by A.R. Kulkarni, a Brahmin lawyer in Nagpur who had a vast collection of books on the subject and had become a Buddhist missionary without giving up his Hindu identity. Another Savarna interested in Buddhism was Bhavani Shankar Niyogi, a retired chief justice of the Nagpur High Court. Together, they started a Buddha Society, which had a library stocked with books donated by Kulkarni; the library was run by Vasant Moon. As his interest in Buddhism grew, Wamanrao Godbole began to meet Ambedkar regularly from the late 1940s onwards. In 1955, the Nagpur Buddha Society was turned into the Nagpur branch of the Bharatiya Bauddha Jana Samiti, and under Godbole’s leadership, it organised a grand procession—with elephants, camels and a band—on the occasion of the 2,500th Buddha Jayanti.

A handbill issued by Godbole on 21 September 1956 gave basic information about the samudayik dharmantar (mass conversion) to be organised on Sunday, 14 October, Vijayadashami (Dussehra) day. It was to be organised under the aegis of the Samiti; the ceremony was to be performed by Bhikkhu Chandramani, a maha thera (great elder) monk from Burma; and all people ‘desirous of getting themselves converted’ would ‘be able to do so’. The date chosen for the event had a significance, which was explained by the SCF leader R.D. Bhandare in Prabuddha Bharat on 29 September 1956. The ‘Buddhist emperor’ Ashoka observed Vijayadashami as his day of victory. On Vijayadashami, Maratha armies had done seemollanghan (crossing of borders) to wage war. Following those traditions, on the 2,500th Vijayadashami according to the Buddhist calendar, Ambedkar was going to lead a ‘true’ seemollanghan, so that the Untouchables could cross the fortifications of the Hindu religion that had kept them in a state of slavery, and they could savour ‘the waters of a new freedom’.

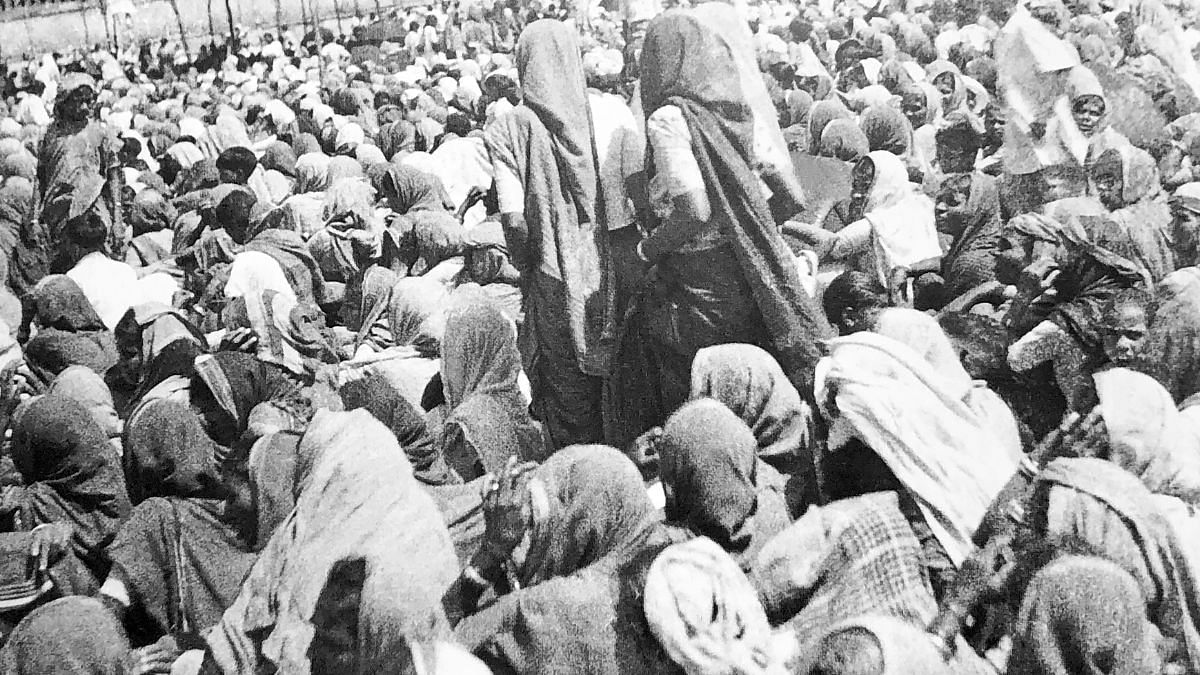

In his announcement on 23 September, Ambedkar had spoken only of his own conversion, and through a statement published in Prabuddha Bharat on 29 September, he once again made it clear that he did not want people to follow him blindly, ‘Properly understand the programme of conversion I have started,’ Ambedkar said. ‘Examine its importance, and decide what you should do’. But for thousands of his Mahar supporters across Maharashtra, the decision had already been made. A correspondent of Navyug reported that on the night of 12 October, Mumbai’s Victoria Terminus was filled with hundreds of people—teachers, lawyers, railway workmen, millworkers, municipality workers, aged persons and whole families—waiting to go to Nagpur. The Nagpur Express was overfull, and the Central Railways arranged for a special train. At every station on the route, people got in, shouting slogans, hugging each other, laughing with joy. When the train reached Nagpur on the afternoon of 13 October, the passengers were greeted by volunteers of the Samata Sainik Dal. Thousands of people had already arrived in the city, on foot, by bullock carts, motor vehicles and train. Arrangements for lodging had been made in municipal schools, but many families set up makeshift dwellings on the road. Groups of people gathered on roadsides talked about the future—about what ‘Bamans’ in their village would say after their conversion; how they would have to stop going to Pandharpur on a pilgrimage; how they would have to stop believing in ghosts and spirits. The Navyug correspondent remarked, ‘Lenin had said somewhere: in a time of revolution, people understand in a matter of days what normally takes years to understand.’ The rest of the mainstream press was not moved. In its 14 October 1956 issue, the Sunday edition of The Bombay Chronicle dismissed what was to take place in Nagpur in a small, single-column report with the heading “S.C.F. men get ready for conversion”.

A forty-by-twenty–foot stage surmounted by a replica of the hemispherical dome of the Sanchi stupa had been erected at the venue, the fourteen-acre ground of the Vaccine Institute on South Ambazari Road. A handbill issued by the organising committee had given clear instructions on how people had to arrive at the venue. Wearing clean white clothes, they had to come on foot, in mixed groups of women and men. On the way, they had to utter, ‘Buddham sharanam gachhami’ (I take refuge in the Buddha) and ‘Dhammam sharanam gachhami’ (I take refuge in the dhamma). Intermittently, they had to say together, ‘Bhagwan Buddha ki jai’, ‘Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar ki jai’ and ‘Babasaheb kare pukar, Bauddha dharma ko karo sveekar’ (Babasaheb has issued a clarion call, Buddhism is to be embraced by all). Everyone had to maintain peace and cleanliness during and after the programme.

Significantly, the handbill did not mention the third oath of the Buddhist trisarana (threefold refuge), Sangham saranam gacchami (I take refuge in the Buddhist sangha). The omission was deliberate. Ambedkar had a poor opinion of the sangha, and he had not been keen to take that oath. However, on 14–15 October 1956, Ambedkar and all those who converted to Buddhism did take the third oath. In his reminiscences, Wamanrao Godbole claimed he convinced Ambedkar to take the oath by arguing that ‘taking refuge in the sangha’ meant taking refuge in the Buddha’s conception of the sangha, not what had become of it.

Ambedkar and Savita flew to Nagpur four days before the event. On his instructions, prior information about their arrival was not publicised. Volunteers of the Samata Sainik Dal were posted for his security at Shyam Hotel, Sitabuldi, where he and the other dignitaries were put up. A feared attack by Caste Hindus did not take place. But there were murmurs of opposition from some SCF leaders, who wanted the mass conversion to be organised after the elections scheduled to be held in 1957. Ambedkar called all the leaders to the hotel, and told them, ‘I am going to undergo dharmantar with whoever joins me …. I will consider only them as my people.’ The veiled threat scotched all opposition.

On the evening of 13 October, five bhikkhus performed a paritraan (protection; paritta in Pali) ceremony at the venue, the traditional Buddhist practice to ward off misfortune or danger. At the hotel, Ambedkar addressed a press conference. According to a report published in an “Ambedkar Bauddha Deeksha” special issue of Prabuddha Bharat dated 27 October 1956, Ambedkar told the reporters, ‘I had assured Gandhiji that I would choose the least harmful path. Accordingly, by choosing Buddhism, I am doing a favour to Hindu society, because Buddhism is a part of Indian culture’. That night a more immediate issue cropped up: the Buddha statue to be placed on the stage at the venue. Ambedkar had assumed Godbole would arrange for the statue, and Godbole had assumed Ambedkar would bring a statue from New Delhi. Both assumptions turned out to be incorrect. Fortunately, there was a bronze statue of the Buddha flanked by two chinthe (Burmese, stylised lion images) in the Central Museum of Nagpur. Ambedkar phoned the chief minister of Madhya Pradesh, Ravishankar Shukla, the museum was opened, and the images were brought to the organising committee’s office around midnight.

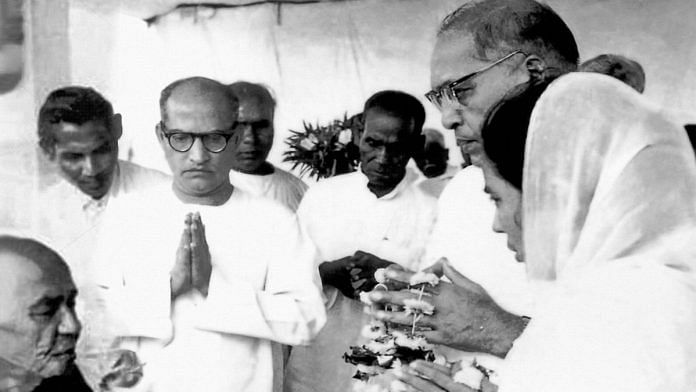

Before sunrise on 14 October, Nagpur turned into a sea of white, as thousands of people marched towards the ground that came to be known as Deekshabhoomi. Following its annual practice on Dussehra day, the RSS, which is headquartered at Nagpur, had also planned for a rally, but there was no clash on the road. Around 9.15 am, Ambedkar and Savita arrived at the ground in a car. He wore a white coat, a silk dhoti and a shawl; she was draped in a white sari. Holding a walking stick and Nanak Chand Rattu’s shoulder, he climbed up to the stage. The bronze idol of the Buddha flanked by chinthe had been placed on a table at the centre of the stage. Blue, red and green Buddhist prayer flags adorned the venue. On the stage were Bhikkhu Chandramani and the other invited bhikkhus, Devapriya Valisinha, several SCF leaders, and some reporters. At around 9.40 am, Bhikkhu Chandramani administered the oaths of trisarana and panchasheel (five ethical precepts) to Ambedkar and his wife, committing them to the Buddha, the dhamma and the sangha, and the five precepts of not killing, stealing, lying, indulging in sexual misconduct or consuming intoxicants. After reciting the oaths, Ambedkar placed his forehead thrice at the foot of the Buddha statue. Then, in a move that had no precedent in the Buddhist world, he turned to the audience and announced, ‘Now I am going to give you all deeksha into Buddhism. Those who want to renounce the Hindu religion and embrace Buddhism may please stand and repeat after me.’ Except for some press reporters, the entire mass of around 400,000 people stood up. Ambedkar administered the oaths of trisarana and panchasheel. In another unprecedented move, he then administered twenty-two oaths drafted by him in Marathi. Eight of those oaths referred to a complete break from the Hindu religion and its beliefs and practices. Two oaths were about equality. The rest were about commitment to the Buddha’s dhamma, but not entirely in the way it was traditionally affirmed. The panchasheel oaths were repeated, but the oath of abstaining from killing was positively framed as ‘I shall be compassionate to all living beings and nurture them with care’. The trisarana oaths were not repeated in toto. Instead, the commitment to Buddhism was affirmed through the following oaths:

I shall not act in any manner contrary to the principles and teachings of the Buddha … I shall follow the eightfold path taught by the Buddha. I shall follow the ten paramitas enunciated by the Buddha. …. I shall strive to lead my life in conformity with the three principles of Buddhism i.e., pradnya (wisdom), sheel (character) and karuna (compassion) …. I firmly believe that the Buddha Dhamma is the Saddhamma. I believe I am entering a new life. Hereafter I pledge to conduct myself in accordance with the teachings of the Buddha.

Together, the twenty-two oaths formed the dhamma deeksha Ambedkar had mentioned to Devapriya Valisinha. They represented, at least partly, his idea of the Buddha’s dhamma—or what came to be called Navayan/Navayana, a new ‘vehicle’ of Buddhism.

This an edited excerpt where the academic notes and references have been removed. Excerpted with permission from Navayana.