The message was clear at Delhi’s Teen Murti: “the other story” of how India won its freedom from the British has the Indian government’s stamp of approval. And this story is about revolutionaries, armed struggle, and the sacrifices of lesser-known Indians.

Home Minister Amit Shah declared that those responsible for “telling the complete story” about the Indian Independence movement “did not do their job well.”

This history was written from the perspective of “angreziyat,” according to Shah. And now, finally, books are being written about the other side of history — the side that should be passed down to the next generations, he said.

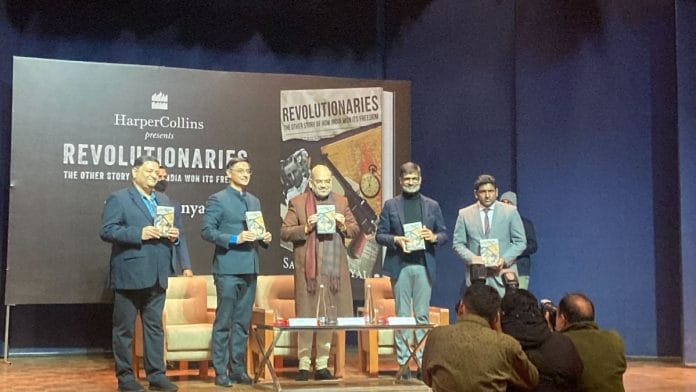

He was speaking at the book launch of economist Sanjeev Sanyal’s Revolutionaries: The Other Story of How India Won Its Freedom on 11 January.

The who’s who of Lutyens’ Delhi had gathered at the erstwhile Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, now renamed Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya. The guest list included Niti Aayog Vice Chairman Suman Bery, journalist Navika Kumar and Information Commissioner Uday Mahurkar. Ambassadors were also invited. Screens were erected outside the auditorium hall for those who didn’t get seats inside.

A hush fell over the audience as Shah took his place on the dais and Sanyal made his introductory remarks.

Shah looked relaxed, adjusting his kurta, rearranging his legs, and straightening his shoulders. When it was time to speak, he paid his respects to Lal Bahadur Shastri, on his 57th death anniversary, and launched into a 45-minute speech on the importance of presenting the “right message of history.”

Shah’s speech and the subsequent conversation attacked the dominant narrative that the Indian Independence movement was led solely by the Indian National Congress. Sanyal’s book, according to Shah, would help undo this narrative for the upcoming generations. He also talked about how understanding this narrative isn’t enough: everyone must also accept it.

“This is our moment in the sun,” said Sanyal, later during the event. “I’m making my little contribution to the cause.”

Also read: Maharashtra passes resolution against Karnataka’s ‘unjust, anti-Marathi’ stance on border row

The “other story” of how India won its freedom

The event opened with a video made for the book: a slideshow of images and videos set to a rousing rendition of the third and fourth stanzas of Vande Mataram, which are not a part of the official National Song. The images included photographs of the Andaman jail where Savarkar was imprisoned, the house where the RSS was founded, the fort in Salimgarh where INA soldiers were kept, and Caxton Hall, where Udham Singh assassinated General Dyer — all related to the revolutionaries whose stories Sanyal chronicles in his book.

Shah’s speech also underlined the importance of these revolutionaries and their contributions to the freedom struggle and talked about how they were never given their due in the annals of history. The other major theme of the discussion was the side-lining of historians like RC Majumdar.

“In India, there was a definite, deliberate attempt to suppress this line of history,” said Sanyal in conversation with Samir Saran, the president of the think tank Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

Sanyal seemed to be pointing to the importance of nuance. Bhagat Singh, for example, is a figure seared into nationalist memory — and is also a figure claimed by both the Left and the Right in India. Sanyal said that while Bhagat Singh was a Marxist, his inspiration was Sachindra Nath Sanyal — a revolutionary who was “vehemently” anti-Marxist.

He said that the same understanding should be extended to maligned figures like Savarkar, or Hindu modernists like Swami Vivekananda. They cannot be placed in “boxes convenient to today’s debates,” according to Sanyal.

“The fact that they’re unapologetic Hindus should not suggest they are bigots,” said Sanyal. “Their nearest lieutenants are not Hindus — like Savarkar and Madame Cama, Bismil and Ashfaqullah Khan, Tilak and Joseph Baptista.”

Also read: Vajpayee to Modi, why India-Pakistan secret peace dialogues on Kashmir have always failed

Who gets to tell the story?

Sanyal’s book tells the interwoven stories of several revolutionaries who took up arms to fight the British. It also explains the multiplicity of ideological streams within the Congress.

“I always felt that the story of India’s independence was incomplete,” said Sanyal, and added that there was an angst about not knowing all the pieces of the puzzle.

Saran called Sanyal’s writing intimate and absorbing. He mentioned that Gautam Chikarmane, Vice President of ORF, had told him before the event that he would likely fail a history exam if he studied Sanyal’s book for it.

Audience members seemed enthralled with the book. Himani Vasudev, a Ph.D. scholar of Sanskrit at JNU, picked up two extra copies for her colleagues. “We can’t wait to read it,” she said. “I’ve been discussing the book with my friends in our group.”

Amit Shah’s speech ended with appreciative whispers about his fine oratory, and Sanyal’s various examples of what he referred to as historical ironies drew laughs and claps.

But perhaps the most interesting question came towards the end of the session, after Shah and most audience members had left. “Is it time to remove the government from the task of writing history, and instead promote writers and historians who perhaps write competing histories?” asked Saran.

Sanyal’s response was yes, absolutely, more people should be writing about history — but the government should play a role in certain areas like standardising government textbooks, and administration over national monuments.

It echoed Shah’s call during his speech for more students and teachers of history to identify 300 personalities and 30 empires that made India a great country. The appeal was to shift focus from a “one-sided history” that paints India in bad light — writers like Sanyal are heralding this change, according to Shah.

Halfway through his speech, Shah wondered aloud if Sanyal’s passion for India would turn into disappointment if he ever visits Shah at North Block. “Don’t worry Sanyalji, I’m with you,” he said with a laugh. “Times are changing for India.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)