There are gaps aplenty in Boria Majumdar’s Eleven Gods and a Billion Indians, which should disappoint those looking for an insider’s perspective on Indian cricket.

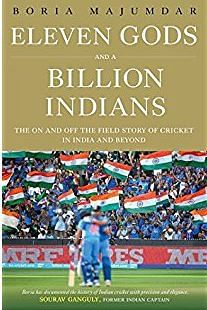

Boria Majumdar’s Eleven Gods and a Billion Indians has a few unshakeable tenets at the centre of it, restated again and again. The phrase, “nationally-unifying religion called cricket,” is one such.

The book is a product of the author’s long career as a journalist and an academic submerged in the world of cricket, both on and off the field. It brings together reportage, historical research, and wild enthusiasm for the sport — but never manages to be enough of any.

Majumdar centres on the financial clout that the sport commands. The fanatic fandom and the monies that come with it are “what Indian cricket is all about.” This to some extent explains Majumdar’s long paean to the IPL, where at one point, he concludes that the success of the tournament, in spite of its occasional murkiness, means that Lalit Modi “stood vindicated.”

This statement comes in a book whose 400-odd pages do not even once mention the ICL debacle and BCCI’s treatment of Kapil Dev through the whole controversy. Such gaps seem frequent if one is expecting to read an insider’s perspective on Indian cricket.

Consider Majumdar’s long chapters on match-fixing, on the notorious tale of Greg Chappell, and on the Harbhajan-Symonds controversy. While an impressive account of the media fervour surrounding the incidents, the book has no answers. It falls back again and again on conclusions like “it remains a matter of conjecture” or “we will never know the real truth on ‘Monkeygate’.”

Any force of argument is cut down when Majumdar says, “I have known Ganguly since 1992. He could never fix matches,” or “I find it hard to believe that Tendulkar would have ‘lied’ about Chappell…” One may be sure that he is completely correct in his assessment, yet such assertions have no place in either journalistic or academic writing.

Why then should Majumdar’s book be read? Solely for the impressive early history of cricket in India, towards the latter half of the book. The chapters on Lala Amarnath’s contentious career, on C.K. Nayudu’s staggering celebrity, and on India’s manoeuvring to host the 1987 World Cup are researched with veracity and the impassioned Majumdar writes with thrill befitting a good storyteller.

He does come back to mentioning, for once, that test cricket is where it is at and not in the big leagues. By then though one is not looking for argumentative consistency— rather, one has settled on the book as a collection of anecdotes and stories from a long career spent looking onto the greens.

Shantam Goyal is a writing tutor at Ashoka University, and is also writing his M.Phil dissertation at the Department of English, University of Delhi.

COMMENTS