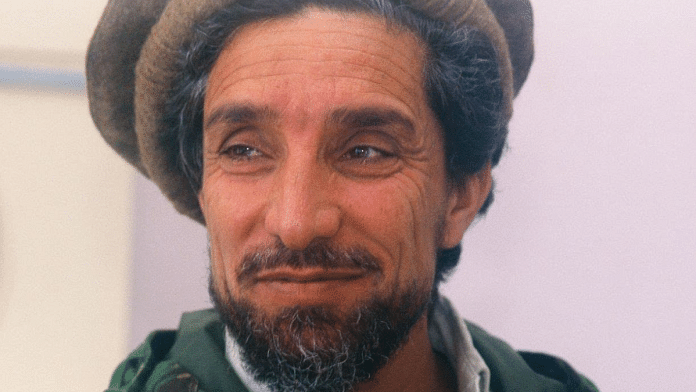

Twelve years after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and after some of the bloodiest fighting seen in the twentieth century, Ahmad Shah Massoud proved himself the outstanding Afghan guerrilla leader to have emerged from the Soviet–Afghan War when he finally captured Kabul. His victory on Wednesday, 29 April 1992 – ahead of his rivals, leading a column of tanks, armoured personnel carriers, and lorryloads of jubilant troops into the centre of the city – was in many ways the apogee of his career.

He ousted Najibullah, the hulking Pashtun former KHAD chief, nicknamed ‘The Ox’, whom the Russians had left in charge. Despite the machinations of Pakistan’s powerful spy agency, the ISI, to gain control of Kabul for its own favourite, the Pashtun extremist Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, they were outmanoeuvred by Massoud, who demonstrated his considerable political as well as military skills by creating a winning coalition. He had forecast that it would take three years after the Russian withdrawal to retrain the mujahideen to fight a conventional (as opposed to guerrilla) war and take Kabul from the communists – and it did.

As well as Massoud’s own tough-as-nails Panjsheri mujahideen, the coalition included troops commanded by two government generals, both of whom had defected to him: Abdul Rashid Dostum’s fierce Uzbek militia, known as the Kilim Jam, and Abdul Momen’s well-trained and well-armed regulars.1 The citizens of Kabul, who had suffered under the heel of the Soviet occupiers and their Afghan communist minions for many years, gave Massoud a hero’s welcome.

The last few weeks of the Najibullah regime were nail-bitingly tense, with Massoud’s lifelong enemy, Hekmatyar, desperately trying to win the prize of Kabul for himself. Fierce fighting – pitting Massoud’s mujahideen and Dostum’s Kilim Jam against Hekmatyar’s Hisb-i-Islami fighters allied with communist troops – raged for several days but, by the time Massoud arrived in Kabul, the battle was over.

For Massoud, it was a victorious end to the long, brutal, and bloody nine-year Soviet war – which lasted from 1979 to 1989 – and his even longer battle against communist control in Afghanistan. Much of Afghanistan had been laid waste by the relentless bombing and strafing of the heavily armed Russian invaders. But against all expectations, including those of some Western experts, the Afghan populace and mujahideen not only refused to admit defeat but, in the end, overcame the Russians and forced them to withdraw in failure. Much of the mujahideen’s success was due to their ingrained determination to defend their country, come what may – but a large measure of that success can be attributed to the guerrilla genius of Massoud.

Also read: When Javed Akhtar met Faiz by pretending to be his friend. It was a close shave

As well as being a personal victory, Massoud’s capture of the capital was the final victory of the Afghan resistance, and of the decade-long campaign backed by the United States against its rival superpower. It was an irony that Massoud – who had long been marginalised by the ISI (with its own agenda for Afghanistan), the CIA, and the US Department of State – was the one who delivered that victory. The CIA had showered millions of dollars on Hekmatyar, because the president of Pakistan, General Zia-ul-Haq, saw him as ‘Pakistan’s man’ in Afghanistan. Zia dictated ISI policy and, since the Americans were close Cold War allies of Pakistan, they followed suit.

Massoud, however, outsmarted them all with his capture of Kabul, leading Robert Kaplan to famously describe him in the Wall Street Journal as ‘the Afghan who won the Cold War’.3 Kaplan, who spent considerable time as a correspondent in Afghanistan for a number of major American publications in the 1980s, described Massoud in glowing terms:

He must be judged among the greatest guerrilla leaders of the 20th century, shoulder to shoulder with Marshal Tito, Ho Chi Minh, Mao Tse-tung, and Che Guevara. He organised a functioning polity over a sprawling, more difficult terrain, that was under greater military pressure, than those of Mao, Ho, Tito or Che. Most significant, Mr Massoud accomplished this without a severe ideology and its accompanying human rights violations.

Kaplan added that Massoud got very little help from the United States. The decisive turning point had come at the beginning of 1992, when President Najibullah tried to replace one of his top commanders, General Momen, who – although Najibullah did not know it – had been in close touch with Massoud for several years. Momen, who was a Tajik, like Massoud, had refused the order, starting a revolt which soon included the most powerful warlord on the government side: General Dostum. At Momen’s instigation, the rebel generals had put themselves under Massoud’s command. He controlled the border port of Hairatan and, soon afterwards, in March, Dostum’s troops had captured Mazar-i-Sharif, the most important city in the north. The writing was on the wall: a few weeks later, Massoud was at the gates of Kabul with Momen at his side.

Watching from London, ITN had scrambled to send three reporting teams to Kabul to cover what seemed to be the imminent fall of the capital. I arrived on the scene just in time and managed to join Massoud at a base at Jebal Seraj outside the city. That day, Massoud had issued an ultimatum to Hekmatyar, calling him up from a captured Russian BTR in Charikar, a small town north of Kabul.

‘We had a long talk on the radio,’ Massoud told me, ‘and I told him,

“Stop your men attacking Kabul, or I will enter Kabul myself.”’ Massoud explained to me, ‘If Gulbuddin [Hekmatyar] does not cooperate with the new [mujahideen] government, if he continues to attack the city, and if he does not withdraw his troops, I will enter Kabul myself tomorrow morning.’

‘Do you have the troops to do it?’ I asked.

‘Yes, I have 6,000 troops in Charikar, and tanks and jets in Mazar-i-Sharif and Bagram [Air Base], which I can use against him. Gulbuddin asked me if I was angry. I said, “No, not as angry as you will be later.”’

That ‘later’ would only have to come if Hekmatyar ignored Massoud’s ultimatum. Next morning, we heard on the BBC World Service that a ‘prominent guerrilla leader’, meaning Hekmatyar, was still objecting to the plan for a mujahideen government. It sounded as if confrontation were inevitable.

I sat writing my diary in the garden of the house in Charikar where I was staying – a former KHAD headquarters requisitioned by Massoud’s forces.

It was a beautiful spring morning, and the apricot tree beside me was thickly covered with the tenderest pink blossom. The long, harsh Afghan winter was over; the fragile beauty of spring was all around us. But as I enjoyed the sunshine, I wondered: would the spring bring with it a bloody offensive?

Later, a few miles up the road, in the small town of Jebal Seraj, we were standing outside Massoud’s headquarters when we heard a clatter of rotor blades as several Russian-built Mi-8 helicopters came swooping in from the direction of Bagram. They were empty, and we soon discovered– as we watched a contingent of troops being marched up the hill – that Massoud was about to carry out his threat to Hekmatyar of airlifting troops into Kabul.

Massoud himself appeared shortly afterwards and confirmed that the troops now embarking were indeed destined for Kabul. After a brief word with the crews, he said a prayer, and then the Mi-8s started their engines and took off; they climbed towards the sunlit, snow-covered Hindu Kush mountains before turning south towards Kabul.

As Massoud and I walked down the hill together, he explained, ‘I’m sending my men to Kabul not to attack the city, but to control it. Gulbuddin does not agree with my proposals.’ In other words, Hekmatyar had rejected Massoud’s ultimatum calling on him to stop attacking the capital and to join the interim government.

Hekmatyar’s latest attempt to take Kabul relied on his customary approach of intrigue backed by force. Having failed to engineer a political coup against the communist President Najibullah in 1990 – despite having the help of the turncoat defence minister, General Shahnawaz Tanai, and the Pakistani ISI – the wily Hekmatyar was now attempting a military-style coup.

Extracted from Afghan Napoleon: The Life of Ahmad Shah Massoud by Sandy Gall. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2022.

Extracted from Afghan Napoleon: The Life of Ahmad Shah Massoud by Sandy Gall. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2022.