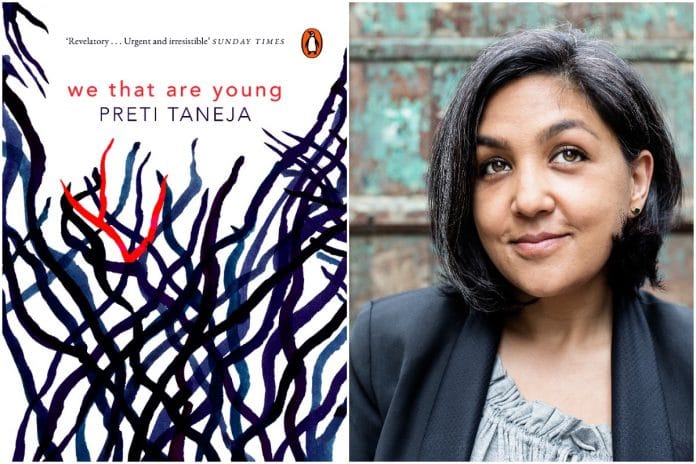

Preti Taneja’s debut novel ‘We That Are Young’ is a perfect cocktail of well-etched Shakespearean characters in contemporary India.

‘We That Are Young’ is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s King Lear in modern India, at the centre of which is the politically charged, corporate dynasty created by the ageing patriarch Devraj Bapuji and his three daughters— Gargi, Radha and Sita. Intermingling with their lives are three more people— Ranjit Singh, the right-hand man, and his sons, Jeet and Jivan.

Preti Taneja’s debut novel, is as tightly woven as it is captivating. It is a perfect cocktail of well-etched Shakespearean characters in contemporary India and a tragedy, with an aftertaste of Bollywood. Devraj is ready to pass off his business empire to his daughters, when the youngest and most favourite daughter Sita, absconds, leaving her inheritance behind. The eldest daughter Gargi takes charge and the company’s slow downfall begins.

On the other hand, Jeet and Jivan are childhood friends of the three girls. The novel begins with Jivan, Ranjit’s illegitimate son, returning to India from the US, after his mother’s death. He intends to have a share in the ever flourishing company. The legitimate son, Jeet, lives under the shadow of his father and godfather. He is burdened by the immense expectations imposed upon him and refuses to come out of the closet.

“It is not about the land, it’s about money,” Jivan keeps repeating to himself, a staccato beat that marks the very fabric of the Shakespearean tragedy and the plot of this novel. The theme goes hand in hand with Devraj’s misogyny and oedipal dependency on his daughters, particularly Sita. True to Lear’s megalomaniac tendencies, Devraj refuses to cede control over his daughters, marrying both of them at a very young age, to men who are mere showpieces rather than real human beings with actual personalities. Greed lies at the core of their relationships with each other. Even when all of it falls apart, the reader understands the motivation of the daughters.

At one point in the novel, Gargi, the eldest daughter tells Jivan, the illegitimate son, “Jivan, did your mother use the word ‘sharam’ to you? Of course not, why would she? We girls are stalked by shame from the moment we are born. We cry to escape it. Then we are caught.” To this, Jivan replies, “I know sharam. I am it. Remember? Jivan the back-yard boy.” Both are the victims of patriarchy and can relate to each other.

Taneja’s use of language also deserves mention. With prose written in present tense and an easy flow of dialogue, she creates a rhythm. Her use of English, interspersed with Hindi words is very colloquial.

Another major theme across the novel— is the idea of space. The boundary in which the narrative is set— is essentially between the business class and the economy, between the cars and the people on the street. The characters are not like every other man, both in terms of their birth and upbringing and the author makes it evident in every scene where they interact with the outer world.

The drama then becomes high-arching, true to the Shakespearean tragedy. When a storm, the result of a sudden climate change, forces Devraj to take shelter in the slums, it is a stark parallel to Sita’s propagation of green activism. Bapuji, who was once the reigning patriarch, takes a stand for the underpaid labourers and becomes a leader of the poor.

This is not a story of a family; the author seems to remind us, but the story of an empire that impacts a nation. As the strong ones become weak and the next generation appears, the narrative stays true to its source material. Although the reader knows what is to come, they turn the pages with a tense foreboding in the air.

The real villains in this novel are the sympathetic characters. In an age of feminism, where Times has awarded Person of the Year to those who have come out to talk about sexual harassment and violence, the reader would find themselves invariably rooting for these children, who have been treated as an afterthought by their fathers.

The weakest point of the novel remains its end. Despite having strong individual characters like Gargi, Jivan and Radha, it peters out as a fatalist tale. The tension of gender politics steadily builds but goes nowhere and the ending feels like an easy way out.

The author is a postgraduate in Journalism and English literature from Indian Institute of Mass Communication and the University of Delhi, respectively.