The book tells a tale of love and loss, saints and sinners, patriarchies and peripheries along with the trials and tribulations shared by marginalized people in modern-day Pakistan.

Academics and social theorists have long regarded the Body as a site of cultural resistance, as well as a site of violence. Renowned French scholar Michel Foucault’s concept of “biopower” talks about “an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugations of bodies and the control of populations” theorizing how the modern nation state uses physical bodies to regulate its subjects.

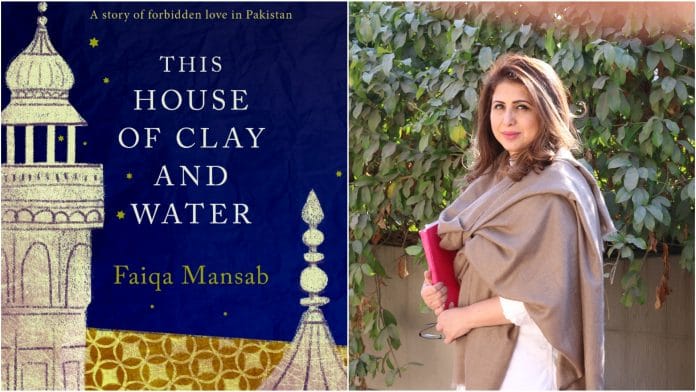

It is in this idea of bodies that author Faiqa Mansab imagines her book, ‘This House of Clay and Water’, set in Lahore. Dubbed a “story of forbidden love in Pakistan”, the book pieces together a tale of love and loss, saints and sinners, patriarchies and peripheries along with the trials and tribulations shared by people whose bodies inhabit spaces of marginalization and subversion in modern-day Pakistan.

Mansab successfully experiments with style and form as each chapter’s heading discloses the character from whose narrative voice the story is being told. The book’s three main characters are Nida, Sasha and Bhanggi. At the start of the story, we see both Nida and Sasha as women who have so far led discontented and disenchanted lives, caught up between troubled marriages and societal expectations.

Caged between the casual sexism flung at her from her husband, mother-in-law and her own brothers, Nida finds herself seeking refuge at the Daata Sahib dargah where she encounters Sasha. Sasha isn’t as affluent as Nida, but impulsive and aspirational, unapologetic in her sexuality as she flits between partners, unhappy with the middle-class lifestyle her husband has to offer. The novel isn’t so much about the Hows and Whys behind these lives, as much as it deals with the ways in which the protagonists seek to break out from this.

It is in this journey of breaking away and seeking meaning to life that Nida also meets Bhanggi at the dargah. Bhanggi is identified as a ‘hijra’, who was born intersex and grew up in poverty. It is worth noting Mansab’s choice of name – ‘Bhanggi’ – is also considered a caste slur, referring to an oppressed caste community of the subcontinent.

Though no mention is made to this, the name choice seems to have been deliberate – the author’s idea to denote being cast(e) away for someone who is doubly marginalised also as a hijra. As the relationship between Nida and Bhanggi evolves, the novel charts their paths of engaging with spirituality, self-fulfillment and negotiating what it means to be a Muslim.

The prose is occasionally over-embellished, and the book can feel a bit exasperating in parts. At times, there are emotionally triggering themes, from child sexual abuse to death to blasphemy and the treatment of minorities in Pakistan, that don’t always fit together seamlessly with the writing, making it awkward to read.

Moreover, with lines like “I’d morphed, altered, nipped and tucked away bits of my personality for so long, I no longer recognized myself” or a “Life is exacting and cruel. Death is calm oblivion. Life betrays everyone while death, without fail, always finds us”, the writer’s attempts at profundity are sometimes overdone despite her heart being in the right place. The descriptions of Lahore too, often feel like it is speaking to a non-Pakistani reader first, not an insider familiar with this part of the world.

‘This House of Clay and Water’ manages to put forth a compelling tale, albeit with a dose of social critique and personalities that could do with more nuance and subtlety. Mansab pens characters who may at times possess too many clunky contradictions to be believable, but it is nevertheless a story which provides readers with themes that need to be introspected.