Nandini was in eighth grade at Ravenshaw Girls’ School, when her uncle died in jail. At the time, communist leaders, Sarat Patnaik and Baidyanath Rath, were impressed by young Nandini’s passion for social work. They motivated her to partake in party activities. As days passed, she began to juggle homework and social work which featured going home to home to meet the poorest of landless tillers and recording their concerns with a pen and paper, and even mobilise them against the nexus of the British government and zamindars. Orissa was drought-and-flood-prone and its people battled starvation, cloth, and shelter.

As a child, she didn’t know Mahatma Gandhi but knew that she wanted to embrace khadi. Her friends used to criticise her for wearing khadi instead of pretty dresses the little girls were gifted on the occasion of Kumar Purnima. During 1942’s Quit India Movement, Nandini was in the sixth grade. Once, during mathematics class, she heard chants of ‘Inqelaab Zindabad’ at a distance. Immediately, she dropped the pen on her notebook and ran out of the classroom towards the boundary wall of the school. Three boys from her class also chased the sound of the rally and ran behind her. One of them was Hrudanand Ray, who later became an eminent Oriya poet and professor of Philosophy.

Nandini wanted to jump over the gritted boundary wall and join the rally that sang: ‘E aajadi jhuta hai, Bhulo mat, Bhulo mat…Aajadi ladhkar lenaa hai, Ladhkar lenaa hai.’ (Don’t forget that this freedom is an illusion. We must fight and fight to seek real freedom). The boys were frightened at the thought of punishment so they returned to the classroom, but Nandini feared no one. She jumped over, her soft palms falling flat on a muddy road. The British police thrashed this little muddy protestor and dumped her in the wilderness of the Chandaka Jungle, which was turned into an elephant sanctuary in August 1982.

Back home, everyone was worried. Bhagabati Charan pedalled along Cuttack’s roads in search of his niece. Submitted to revolution and literature himself, he had little reason to stop her from doing what she was doing. But Nandini was a minor. That day, he found her at Chandni Chowk, Cuttack, limping back home. Despite receiving a scolding from him, she proudly stated that the police had held her hostage. He smiled and said, ‘It seems as though Gandhi and Nehru will find it hard to get us independence but little Kuni will surely fulfil this duty.’ Her uncle died the following year. Nandini went on to complete tenth grade and made it to Ravenshaw College.

On 18 December 1946, the annual sports event of Ravenshaw College was taking place. His Excellency Shri Chandulal Trivedy, Hon’ble Governor of Orissa, and Shri Nabakrushna Choudhuri, Hon’ble Revenue Minister, were the chief guests. During the event, students from the college wished to hoist the national flag. Nandini Panigrahi, along with Manmohan Mishra, Jagat Krushna Das, Purnanand Das, Girija Patnaik, Nirupama Rath, and Shyamali Lahiri, decided to raise the tricolour.

In one heartbeat, she uprooted the Union Jack from a stately red edifice and made the tricolour flutter across its own blue skies, high above the horizons of Cuttack. In one instance, Nandini went from being the niece of a slain revolutionary to a huge leader in the making. Given the furore such an incident could invoke, the students were immediately arrested by the British police and detained at the Ranihat Square police station. Here, Nandini made a strong statement asking whether Harekrushna Mehtab, the then Chief Minister of Orissa, had doubts about India’s ability to attain freedom, when he didn’t question the Union Jack’s presence.

As a 15-year-old, she perhaps did not understand the magnitude of her act but in the academic ecosystem, among student federations, in political circles, and in the press, Nandini became famous as the girl who took down the Union Jack.

Back in the ’40s, for a girl to display such daredevilry was quite rare. Today, nine decades after, women in many parts of the country are still struggling to clamber out of domestic chambers and find a life and a voice in public life. In the book Matira Nandini, she talked about the faith that her father had in her capabilities.

The family erased the scribblings of patriarchy. When her younger brother, Shishir, graduated from school, their father, Kalindi Charan, wanted to throw a party. This upset her mother so she asked why there wasn’t any celebration to mark Nandini’s first division when she graduated from the Ravenshaw Girls’ High School in 1946. Her father replied that he knew Nandini would pass with flying colours and that there was no need to celebrate what was bound to happen. The unshaking faith in her credibility gave her the strength to keep going.

Nandini’s younger sister, Yashodhara Mishra, wasn’t quite like her. ‘Trying to imitate her older sister to earn appreciation from their father, her younger sister (whose nick name was Lucy) had locked herself up in our father’s study once. She sat inside and smoked a Marco Polo cigar and scribbled some incomprehensible lines, in the hope of being like her sister,’ Sudha Panigrahi narrated this story that was recited quite often at family gatherings.

Often dressed in starchy, cotton white sarees, Kuni nani (sister) to her younger siblings and their spouses, went about meeting the poorest of the poor in Orissa’s villages as a student leader at the Communist Party of India. Before she turned 20, she had been in and out of jail many times for communist party activities. She would give fiery speeches on college campuses, inciting anti-British sentiments. She would also organise large groups to paint and stick anti-British posters on walls.

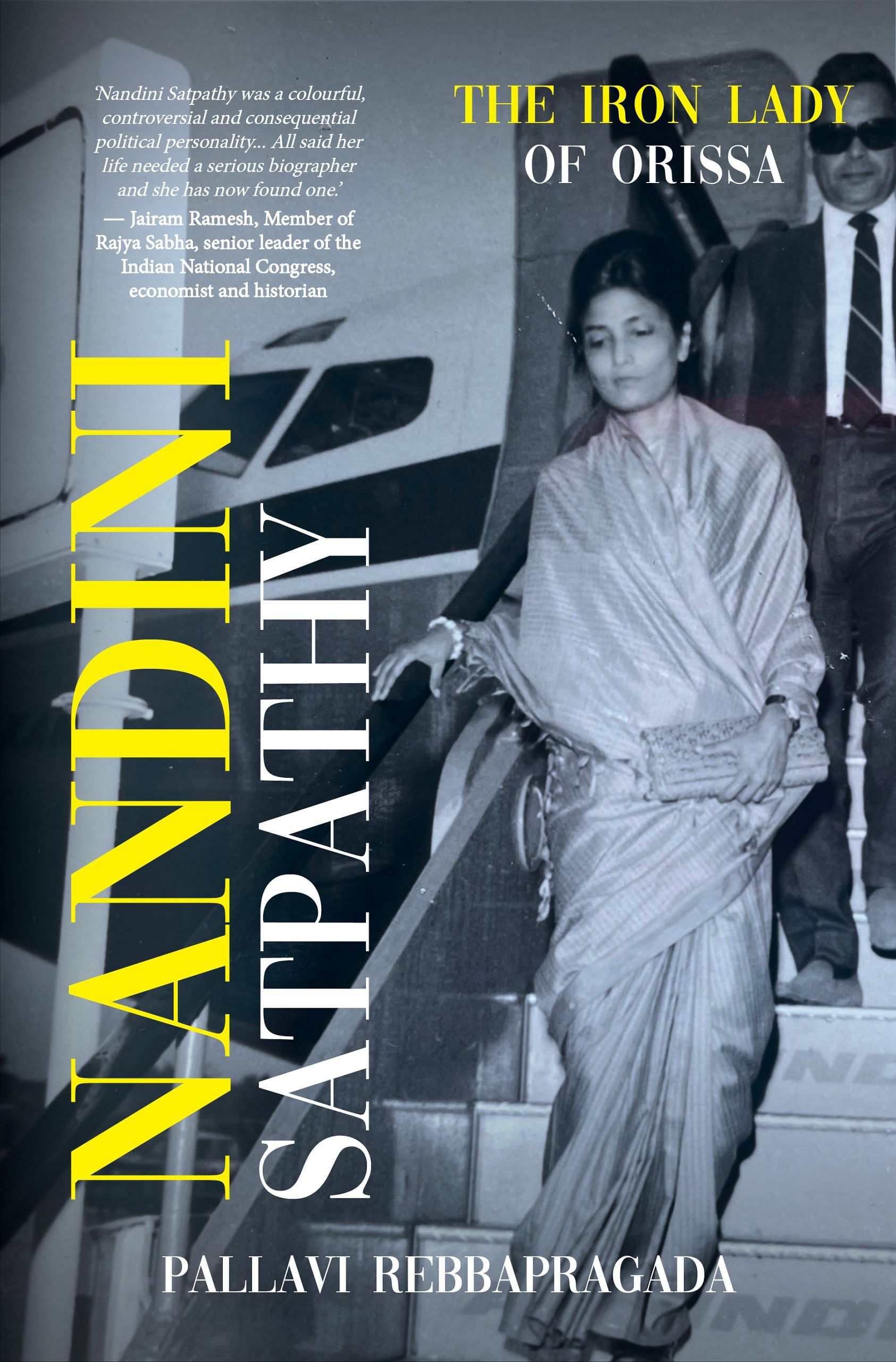

This excerpt from Nandini Satpathy: The Iron Lady of Orissa by Pallavi Rebbapragada has been published with permission from Simon & Schuster India.

This excerpt from Nandini Satpathy: The Iron Lady of Orissa by Pallavi Rebbapragada has been published with permission from Simon & Schuster India.