The curtain fell in the old-fashioned way: The state-of-the-art Hawker Siddeley HS-121 Trident jet exploded in the great emptiness of outer Mongolia’s Öndörkhaan desert in 1971. Lin Biao, the revolution-era military hero and Marshal of the People’s Republic of China, who was on the flight with his wife Ye Qun and son Lin Liguo, was declared a traitor hours later. The old marshal, the People’s Republic of China alleged, had sought to flee after trying to assassinate Chairman Mao Zedong.

Even the Central Intelligence Agency, its part-declassified investigation shows, struggled to sift truth from fiction on just how and why the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) most storied hero had been killed. There was no evidence that Project 571, Lin’s alleged assassination plot against Mao, had begun: “No bullet was fired, no bomb exploded.” The report said that Lin might even have been executed at the summer resort of Peitaiho, where he was vacationing.

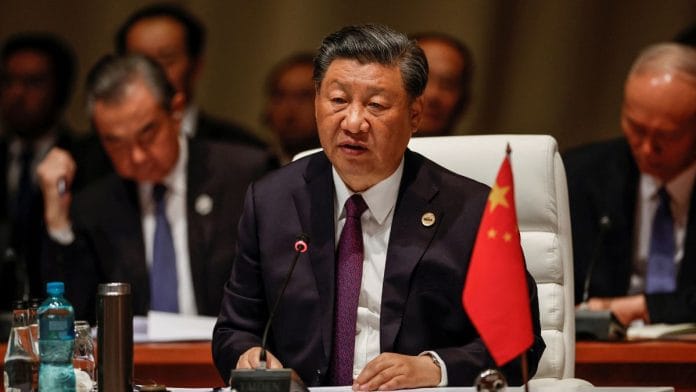

The story has emerged again from musty history books, as Chinese President Xi Jinping begins the most significant purge of the political system since the landmark anti-corruption churning of 2017, when more than 170 ministers and deputy minister-level officials were removed. Almost 1.34 million officials—from so-called “flies” to “tigers” including Zhou Yongkang, the country’s third-most powerful politician. The purge was key to Xi consolidating unchallenged power in China.

Also read: Xi purging military brass has a message—It’s CCP that calls shots in China, not PLA

Falling off the wall

Li Shangfu, China’s powerful defence minister, hasn’t been seen in public since August—and western intelligence services are reporting he has been quietly removed from office. General Li Yuchao, the commander of the PLA Rocket Force, which controls both the country’s conventional and nuclear land-based missile arsenal, has similarly vanished.

Chinese foreign minister Qin Gang was announced to have been removed, but the grounds haven’t been made public. The elderly former president of China Hu Jintao and globally-reputed businesspeople such as Jack Ma and Guo Guangchang disappeared while their businesses were dismantled. Even the actress Fan Bingbing vanished for almost a year, and later reappeared after settling a tax-related case.

Last year, journalist Frédéric Lemaître reported the first signs of the purge gathering momentum, with the dismissal of four high-ranking police officials, both on corruption charges and allegations of plotting against Xi.

There’s no shortage of conjectures on what’s going on in China. Journalist Brendan Cole has suggested Xi is acting to prevent a Wagner Group-style praetorian rebellion; others believe the president is taking on an old guard concerned about his economic policies and high-risk confrontation with Taiwan.

Even simpler explanations exist. Michael Rowand, a researcher at the Federal Research Division of United States Library of Congress, suggests the purge is about removing potential opponents to Xi, who might have gathered too much institutional power and could prove future rivals.

“This thing, power, depraves people,” Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, once remarked. For centuries, despots have known that the most refined form of depravity is to use terror arbitrarily, so no one knows for certain which actions might be punished, to what extent, and when.

Also read: CCP’s annual retreat is not a vacation. There’s a leadership crisis in China’s Rocket Force

Family, memory and trauma

The story of Xi’s purges—or at least a way to understand their motivations—is tied to his most intimate memories of exile from the gates of power. His father had served the Chinese communist revolution from its genesis, and was admitted to the party’s all-powerful Central Committee in 1956. He became the vice-premier in 1959, directing the state council’s lawmaking role and various core research roles.

From 1962, though, expert Joseph Torigian has recorded, things began to go horribly wrong—over a book. The elder Xi defended a biography of the revolutionary hero and military commander Liu Zhidan. According to the Chinese intelligence czar Kang Sheng, the book contained veiled anti-communist heresies.

Xi Zhongxun was demoted, and sent off to serve as deputy manager of a tractor factory in remote Luoyang. Qi Xin, his wife, was sentenced to hard labour on a farm. In early 1967, journalist Evan Osnos has written, the elder Xi was humiliated by the lumpenised Red Guards who seized power during the so-called Cultural Revolution. Among other things, he was accused of having longingly gazed at West Berlin through binoculars.

During this tumultuous period, the impact of the Cultural Revolution was felt not only in China but also influenced global perceptions of governance and ideology.

For years afterward, Xi Zhongxun would recall that he had been held in a military garrison and that he maintained his sanity by walking in circles, ten thousand laps one way and then ten thousand the other. Xi, the son, was sent off to work in the remote village of Liangjiahe, Shaanxi Province, from 1969 to 1975. Several accounts agree that he encountered tremendous hardship and deprivation there.

Educated at the super-élite August 1st School—run from a former imperial palace—Xi Jinping also had to unlearn his privilege. Discipline at the school was tough—Torigian writes that students were sometimes beaten, and “forced to eat old rice contaminated by rat faeces”. From 1966, though, the school’s little princes were being confronted by Red Guards who proclaimed: “If the father is a reactionary, the son is a bastard.”

At the age of just 14, according to one account, Xi was threatened with execution by Red Guards. Though he went on to study at the prestigious Tsinghua University in Beijing. After graduating in 1979, Xi secured a job in the Central Military Commission as the youngest of three personal secretaries for then defence minister Geng Biao. Likely, though, the brutal experiences of those years did not have a lasting psychological impact.

Following the end of the Mao Zedong era, his father Xi was rehabilitated and returned to the Politburo in 1982, journalist Katsuji Nakazawa writes.

Nakazawa suggests it’s likely that Xi learned his lesson: “In a power struggle, if either side fails to make a pre-emptive attack, it will eventually be pinned in and handcuffed by the other side. Those on the losing side will be wiped from history, while the victor goes down as a great figure. Even Mao, despite his disastrous policies that resulted in tens of millions of deaths, is widely respected.”

Also read: Border defence is CCP’s new ideological feature. And Xi has a tsar to lead the charge

The terror of the arbitrary

Far too little is known about Xi’s China to support speculations on what might lie ahead. Few experts, Stig Stenslie and Marte Kjær Galtung remind us, gave Xi a chance when he took power in 2012. The knowledgeable journalist and writer Willy Wo-Lap Lam predicted Xi’s tenure would be scarred by the divisive political scandals that led up to the 18th National Congress of CPC. The commentator Nicholas Kristof saw in Xi the kernels of a reforming democrat.

Instead, Xi demonstrated skills few outside the Chinese system had seen in him. He removed key rivals, like former Minister of Commerce Bo Xilai, using the corruption issue like a cleaver. By 2017, he had secured enough support to rule like an emperor. Limits that restricted a president for serving more than two terms—introduced by Deng Xiaoping to prevent a second Mao from arising—were removed.

Xi has built his authority by placing trusted loyalists in place across the system but he has amassed power to the point where loyalty is no longer a distinguishing trait, or a unique qualification. The purge likely serves to send the message that even the highest degree of unquestioning servility does not guarantee survival.

Frank Dikötter perceptively notes that the Chinese system is based on a deeply internalised terror: “When you see the underlings of a leader enthusiastically applaud, then you should feel fear. Because that’s precisely what they feel.”

There will be ever-more clapping in coming months, as the purge unfolds. The course China will take as it navigates economic, demographic and strategic challenges, however, remains entirely unclear.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)