In one of the long drives through the night on Mumbai’s roads in Zoya Akhtar’s Gully Boy, the light falls briefly on a billboard of Made in Heaven. It’s her forthcoming series, co-produced with Reema Kagti, on crazy rich Indians and their weddings for Amazon Prime Video.

It’s unimportant to the movie but shows Zoya Akhtar’s range as a filmmaker. Once dubbed the princess of posh people’s pain, by several critics, including me, Zoya has shown her mettle in Gully Boy. She is a fine storyteller, observer of subcultures, chronicler of deep urban class divides, and poet of possibilities. She ascribes that to her education at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai, in literature and sociology, which taught her to listen carefully to those around her and beyond. “I am interested in human beings and their worlds. What one has to decide on is one’s gaze,” she says.

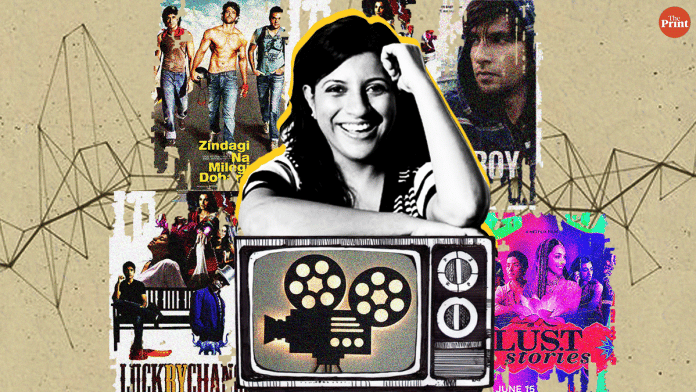

So in Luck By Chance (her first movie in 2009), the perspective is that of a fly on the wall as she watches people dealing with success and failure in the film industry; in Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (2011), the viewer is right there in the car with the guys as they are on the road; and in Dil Dhadakne Do (2015), the point of view is of a dog’s, who observes the Mehras, with and without their masks.

Also read: Zoya Akhtar’s Gully Boy simmers with rage, and allows Ranveer Singh his own Bachchan glory

In Gully Boy, based on the lives of Mumbai rappers Divine and Naezy, Zoya places the camera on the inside but looking out at the Dharavi of corrugated roofs dotted with satellite dishes, of bridges over garbage dumps, of tangled wires sharing space with discoloured exteriors. The actors are shot in close ups, each emotion on their face and each minor flaw in their appearance magnified.

The camera stays largely on the main characters: Murad (Ranveer Singh) as he discovers the angst in his soul translating into poetry that people want to listen to; his girlfriend Safeena (Alia Bhatt) who is studying to be a surgeon despite the restrictive confines of a strict Muslim household that doesn’t allow her to wear her hair loose or sport lipstick or talk to boys; and the electric DJ Sher (a brilliant Siddhant Chaturvedi) who channels his rage against his alcoholic father and his absent mother by rapping his heart out.

Zoya shoots Mumbai with affection and exasperation. She doesn’t miss much. Rich people’s bathrooms that are bigger than a chawl for a family of seven. Foreigners with selfie sticks who are out to record Dharavi’s poverty porn through tour guides. Rappers in chawls who have a safe for their fancy shoes. Working class guardians who are gatekeepers of the world of privilege – whether it is a guard at posh girl Sky’s building, or at the club where Gully Boy will eventually perform, or the silent sentinels at the hotel where he drops his “Madam”.

Also read: Alia Bhatt will rule Bollywood in 2019, and it won’t be because of nepotism

The wildly different graffiti on a night out of spray-painting by Sky (Kalki Koechlin) and Murad tells the story of their difference. Sky sprays “feed me” over model photos in store windows and “brown and beautiful” over advertisements of fair and beautiful. “Sky and Murad are from the same side of the fence,” says Zoya, “but their concerns are so different. She is worried about racism and body dysmorphic disorder; he sprays ‘Roti, Kapda, Makaan Plus Internet’ on the wall – that’s what he is looking for.”

Zoya’s background is well-known. Daughter of poet Javed Akhtar, her mother Honey Irani was a child actor who has written blockbusters such as Darr (1993) and Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai (2000). Her grandfather was the legendary lyricist Jan Nisar Akhtar and great grandfather was another well-known Urdu poet, Muztar Khairabadi. A liberal consciousness has been part of her upbringing. “There is a particular standard of work we are expected to maintain, whether it be in the language used, the vulgarity eschewed and the way we viewed women,” she says. But more than that, she says her biggest influence is her immediate family. Her parents, who separated when she was 12, encouraged her to be free, to “screw up, to do it your own way, but take responsibility for it”.

The first time she decided she wanted to be a filmmaker was when she saw Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay! (1988). Till then, she thought she was a misfit in the Mumbai film industry, which had no place for her kind of sensibility. But in 10 years since her debut film, she has directed four movies, two short films (one was the highly acclaimed short in Netflix’s Lust Stories, where she shows the tenuous relationship that develops between a maid and her employer, and the other was ‘Sheila ki Jawani’ in the 2013 anthology, Bombay Talkies), and a soon-to-be aired web series.

Alankrita Shrivastava, director of Lipstick Under my Burkha, who has co-written the web series Made in Heaven with Zoya and her closest friend Reema Kagti, calls her “most generous, collaborative and hardworking”. “She doesn’t need to surround herself with people who agree with her opinions and thrives on interacting with lots of people.”

That diversity reflects in her work, which is why Gully Boy has struck a chord. It’s not merely because of its poetry and its rhythm although there is that. It is also because it taps into the angst of millennials. Educated young people with limited job opportunities, scavenging for a life. As she says: “Kids today have never left Mumbai and yet they know of the world outside, of Tupac Shakur and Kendrick Lamar. The frustration at the serious disparity is real.” And yet, art can allow them to transcend the class barriers.

Also read: How Ranveer Singh conquered the nepotistic world of Bollywood

Indeed, that art, that talent allows Zoya to be true to herself, to her instincts, to her stories. “Every time something doesn’t feel right, whether it is a scene, a dialogue, an actor or even the colour of the wall, (and) if I don’t listen to my gut, I make a mistake,” she says, refusing to give me details. “Because I write my own material, I have internalised it to such an extent that I know it in my bones.”

At 46, Zoya has clocked an impressive resume but it wasn’t until she was 35 that she made her first movie, Luck By Chance, which was plagued with casting problems. During this time, she worked as an assistant director to brother Farhan Akhtar on his breakout directorial debut Dil Chahta Hai (2001) and the war film Lakshya (2004).

With Gully Boy, which had a successful premiere at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this month, Zoya has acquired a special status. Few filmmakers in India can boast of movies that are critically acclaimed and commercially successful. Gully Boy looks set to do well at the box office. Her peers acknowledge this. Ask friend Anurag Kashyap, and he says: “She is the most exciting filmmaker working in the mainstream today. She cares about the film she makes and is consistently inspiring. I want to be Zoya Akhtar”.

Indeed, as the last lines of Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara say: “Dilon main tum apni betabiyan leke chal rahe ho to zinda ho tum/Nazar main khwabon ki bijliyan leke chal rahe ho to zinda ho tum”.

Or as Murad raps in ‘Apna Time Aayega’: “Yeh shabdon ka jwala meri bediyaan pighlayega/Jitna tune boya hai utna hi to khayenga/Aisa mera khwab hai jo darr ko bhi satayega/Zinda mera khwab, ab kaise tu dafnayega.”

Zoya Akhtar’s words and dreams are as timely as they are full of life.

Kaveree Bamzai is a senior journalist and former editor of India Today.